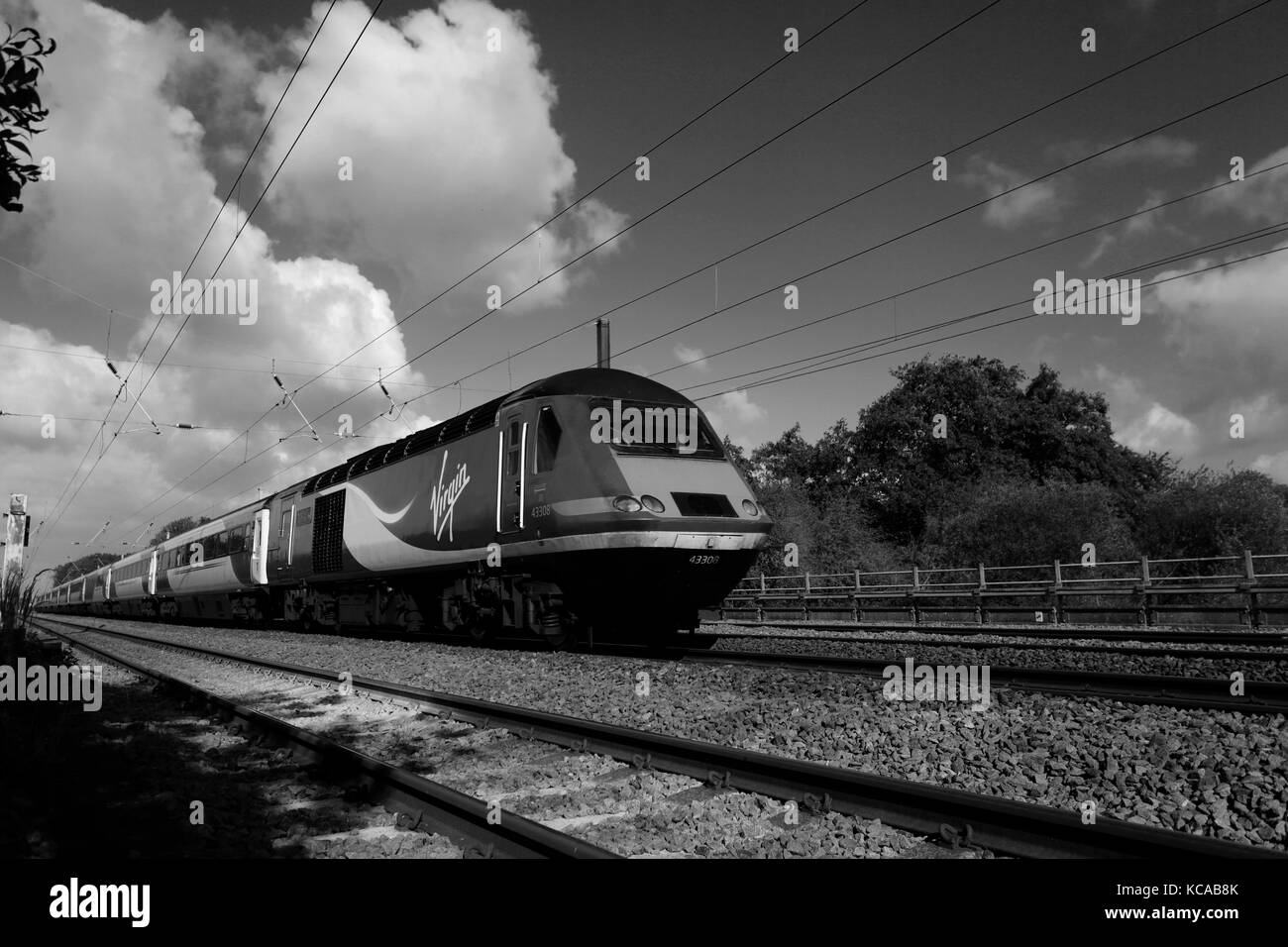

It wasn't supposed to end like this. Back in 2015, when the red-and-white liveries first started appearing on the InterCity 225 sets at London King’s Cross, the hype was massive. You've probably seen the old photos of Richard Branson standing on a platform, grinning like he’d just invented the wheel. The Virgin East Coast rail era promised a revolution for the East Coast Main Line (ECML). It was going to be the private sector’s crowning achievement.

Instead, it became a cautionary tale about how difficult it is to make money moving people between London and Edinburgh.

If you traveled on the route during those three years, you might remember the "Virgin-ized" interiors and the upgraded food menus. But behind the scenes, the finances were basically a slow-motion car crash. By June 2018, the government had to step in. The franchise didn't just fail; it collapsed under the weight of wildly optimistic revenue projections that never actually materialized.

The 3.3 Billion Pound Gamble

When Virgin Trains East Coast (VTEC)—a joint venture between Stagecoach (90%) and Virgin Group (10%)—won the bid, they didn't just win; they dominated. They promised to pay the UK government roughly £3.3 billion over eight years for the right to run those tracks. To put that in perspective, that’s a staggering amount of money for a line that had already seen two previous private operators, GNER and National Express, buckle under financial pressure.

The math was aggressive.

To make those payments, VTEC needed passenger numbers to skyrocket. They were betting on a massive increase in demand that simply wasn't supported by the reality of 21st-century commuting and regional travel. Then, the infrastructure problems started. Network Rail, which manages the tracks, failed to deliver the promised upgrades on time. Without those upgrades, Virgin couldn't run as many trains as they planned. If you can't run the trains, you can't sell the seats. If you can't sell the seats, you can't pay the government.

✨ Don't miss: Nasdaq Composite Explained (Simply): Why It’s the Pulse of Global Tech

Why the "Virgin Magic" Failed This Time

Virgin is a brand built on vibes. It’s about the flair, the cheeky marketing, and the feeling that you’re doing something cooler than just sitting in a metal tube for four hours. On the West Coast Main Line, they actually pulled it off for a long time. But the East Coast was different.

The East Coast Main Line is a beast. It connects the financial power of London with the tech hubs of Leeds and the cultural weight of Edinburgh. It's a premium route. But passengers on this side of the country are notoriously fickle. They want punctuality more than they want a branded snack box. Honestly, the "Virgin-ization" of the line felt a bit like putting lipstick on a pig. While they did refurbish the old Mark 4 coaches, the actual hardware—the locomotives and the track—remained prone to technical meltdowns.

The Azuma Factor

The real tragedy for VTEC was the timing of the Class 800 and 801 trains, branded as "Azuma." These Japanese-designed Hitachi trains were meant to be the savior of the franchise. They were faster, sleeker, and more reliable. But by the time the Azumas were ready to roll out in 2019, Virgin East Coast rail was already dead. The government had already terminated the contract.

It’s one of those weird historical quirks. Virgin spent years marketing the "Azuma" brand, only for LNER (the government-owned successor) to reap all the benefits of the new fleet. You can still see the DNA of Virgin’s design choices in the current LNER service, but the name on the side of the train is different.

The Political Fallout: A "Bailout" or a Necessity?

When the then-Transport Secretary Chris Grayling announced that the franchise would end early, the backlash was fierce. Critics called it a "billion-pound bailout" for Stagecoach and Virgin. The argument was that the companies were being allowed to walk away from their £3.3 billion commitment without paying the full penalty.

💡 You might also like: Why Your Dividend Stocks Retirement Portfolio Might Be Your Only Path to Real Passive Income

The reality is a bit more nuanced, though no less messy.

If the government had forced the companies to keep running the line until they went completely bankrupt, the service would have likely suffered. Maintenance would have been cut. Staff morale would have plummeted. By stepping in and creating London North Eastern Railway (LNER) as an "Operator of Last Resort," the government prioritized keeping the trains moving. But it essentially signaled the end of the old franchising model in the UK. It proved that the system of bidding billions of pounds for a decade-long contract was fundamentally broken.

What Travellers Actually Noticed

If you’re just someone trying to get to a meeting in York or a weekend away in Berwick-upon-Tweed, the corporate drama matters less than the seat quality. Virgin did bring some genuine improvements:

- The Food: Let’s be real, the First Class breakfast under Virgin was actually decent. They brought in James Martin to help with the menus. It felt less like a "train meal" and more like a bistro.

- The Booking App: Their tech was consistently better than the clunky systems used by older franchises.

- The Reward Scheme: Virgin Red and the ability to earn Virgin Atlantic miles on a train journey was a huge pull for business travelers.

But they also faced criticism for "declassifying" certain areas and the constant struggle with Wi-Fi reliability. The ECML passes through a lot of "dead zones" in North Yorkshire and Northumberland, and despite all the branding, Virgin couldn't magically fix the signal issues overnight.

How to Navigate the Post-Virgin Era

If you are planning a trip on the route formerly known as Virgin East Coast rail today, things look quite different. LNER has maintained a high standard, but the "fun" branding is gone in favor of a more professional, understated vibe. Here is how you should handle travel on this route now:

1. Avoid the "Anytime" Trap

The East Coast is one of the most expensive lines in Europe if you buy a ticket on the day. Always use the LNER app (which inherited much of the Virgin tech DNA) to book "Advance" singles. Even booking 24 hours ahead can save you 50% compared to a walk-up fare.

2. The Lumo Alternative

Since Virgin left, we’ve seen the rise of "Open Access" operators like Lumo. They run between London and Edinburgh with a low-cost model. They don't have a First Class, but their seats are often cheaper than even the most discounted LNER tickets. If you don't care about the "Virgin-style" perks, this is the budget way to go.

3. Check the "Delay Repay" Rules

The East Coast Main Line is still susceptible to overhead wire issues and "person on the track" incidents. If your train is delayed by more than 30 minutes, you are legally entitled to compensation. Keep your physical ticket or a screenshot of your e-ticket; LNER is actually quite efficient at processing these, a legacy of the streamlined systems Virgin helped pioneer.

4. The First Class Value Prop

On the old Virgin East Coast rail, First Class was almost always worth it for the food alone. Today, it depends on the "tier" of service. Check if your train is a full meal service or just "light refreshments." If it's the latter, save your money and buy a meal at King's Cross.

🔗 Read more: Charlotte Tilbury Net Worth: Why the Makeup Mogul is Still Winning in 2026

The Lasting Legacy of VTEC

Virgin East Coast rail didn't fail because they were bad at running trains. They failed because the business model of the UK rail system at the time was built on a fantasy. You can't promise billions to the Treasury based on growth figures that ignore the possibility of economic stagnation or infrastructure delays.

Today, the UK has moved toward "Great British Railways," a more centralized model. The era of flashy private brands like Virgin competing for these massive "Big Four" routes is largely over. The red trains are gone, replaced by the sleek white and red of LNER, but the lessons learned from that three-year experiment still dictate how we pay for, and ride, the rails in Britain.

To get the most out of your next East Coast journey, focus on booking at least 8 to 12 weeks in advance when the cheapest "Fixed Link" tickets are released. Use seat maps to avoid the "pillar seats" on the Azuma trains—where you have a window seat with no actual window—and always sign up for the loyalty scheme, as the "Perks" program has replaced the old Virgin Rewards with surprisingly good credit-back offers for frequent riders.