If you watch the local news, it basically feels like the world is ending every single night at 6:00 PM. Sirens. Crime tape. Somber anchors. It’s a lot. But when you actually look at violent crime by year, the reality is way more complicated than a thirty-second news clip makes it out to be. Honestly, the way we talk about safety in this country is usually based on vibes rather than what the FBI is actually reporting.

Numbers don't lie, but they do get misinterpreted. Constantly.

To really understand where we are, you've got to look back at the 1990s. It was a different world. In 1991, violent crime hit a peak that most people today can't even wrap their heads around. We're talking about a rate of 758 incidents per 100,000 people. If you lived through it, you remember. If you didn't, just know that the "bad old days" weren't just a movie trope—they were a statistical reality. Since then? It's been a wild, downward, then jaggedly upward ride.

Why Violent Crime by Year Fluctuates So Much

Why does one year look like a peaceful utopia and the next looks like a disaster zone? It's never just one thing. Experts like those at the Brennan Center for Justice point to a messy cocktail of economic shifts, social stability, and even the "lead-crime hypothesis"—the idea that removing lead from gasoline and paint actually made us less aggressive over decades.

It sounds wild. But the data for the early 2000s shows a massive, steady decline. We were getting safer. Year after year, the numbers dropped. By 2014, the violent crime rate had plummeted to 361.6 per 100,000. That is less than half of what it was in the early 90s. You’d think we’d be celebrating in the streets, right? Well, we weren't, because human psychology is weird. We tend to feel less safe even when the data says we are.

The Pandemic Pivot

Then 2020 happened. Everything broke.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the trend for violent crime by year did something it hadn't done in a long time: it spiked. Specifically, murders went through the roof, increasing nearly 30% in a single year. That’s the largest one-year jump in modern American history. It was terrifying. But here’s the nuance people miss: while homicides spiked, other types of violent crime, like robberies, actually went down because, well, nobody was outside to be robbed.

📖 Related: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

It’s these kinds of contradictions that make "crime" a hard thing to talk about. You can’t just say "crime is up" or "crime is down." You have to ask: which crime? Where? And who is it affecting?

The Great 2023-2024 Cool Down

If you've been following the latest releases from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program, you might have noticed something surprising. After that massive pandemic spike, things started to settle.

By 2023, preliminary data showed a significant drop in almost every major category of violent crime. Murders dropped by roughly 13% in many major cities. It was one of the fastest declines we've ever seen. Richard Rosenfeld, a renowned criminologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, has noted that as social institutions—schools, offices, community centers—reopened and stabilized, the "fever" of the pandemic years began to break.

But here’s the catch.

Even with those drops, we aren't back to the historic lows of 2014 yet. We are in this middle ground. Some cities, like Memphis or New Orleans, have struggled much more than others like New York or Los Angeles. This "geographic inequality" of crime is basically why your uncle in one state thinks the world is fine while your cousin in another state is terrified to go to the grocery store. They’re both technically right about their own backyards.

Decoding the FBI Data Gaps

We need to talk about the "data problem." It's a mess.

👉 See also: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

In 2021, the FBI switched to a new reporting system called NIBRS (National Incident-Based Reporting System). It was supposed to be better, more detailed, more modern. The problem? Thousands of police departments couldn't figure out how to use it or didn't have the budget to switch. For a while, we were flying blind. Major cities like Miami and parts of Los Angeles just... stopped reporting for a bit.

When people look at violent crime by year during this transition period, they’re often looking at "estimated" data. It’s basically the FBI’s best guess. While the estimates are usually pretty good, it adds a layer of uncertainty that politicians love to exploit. You’ve probably heard someone claim crime is skyrocketing while someone else says it’s at a record low. They’re usually just cherry-picking which part of the incomplete data set they want to believe.

Common Misconceptions About Annual Trends

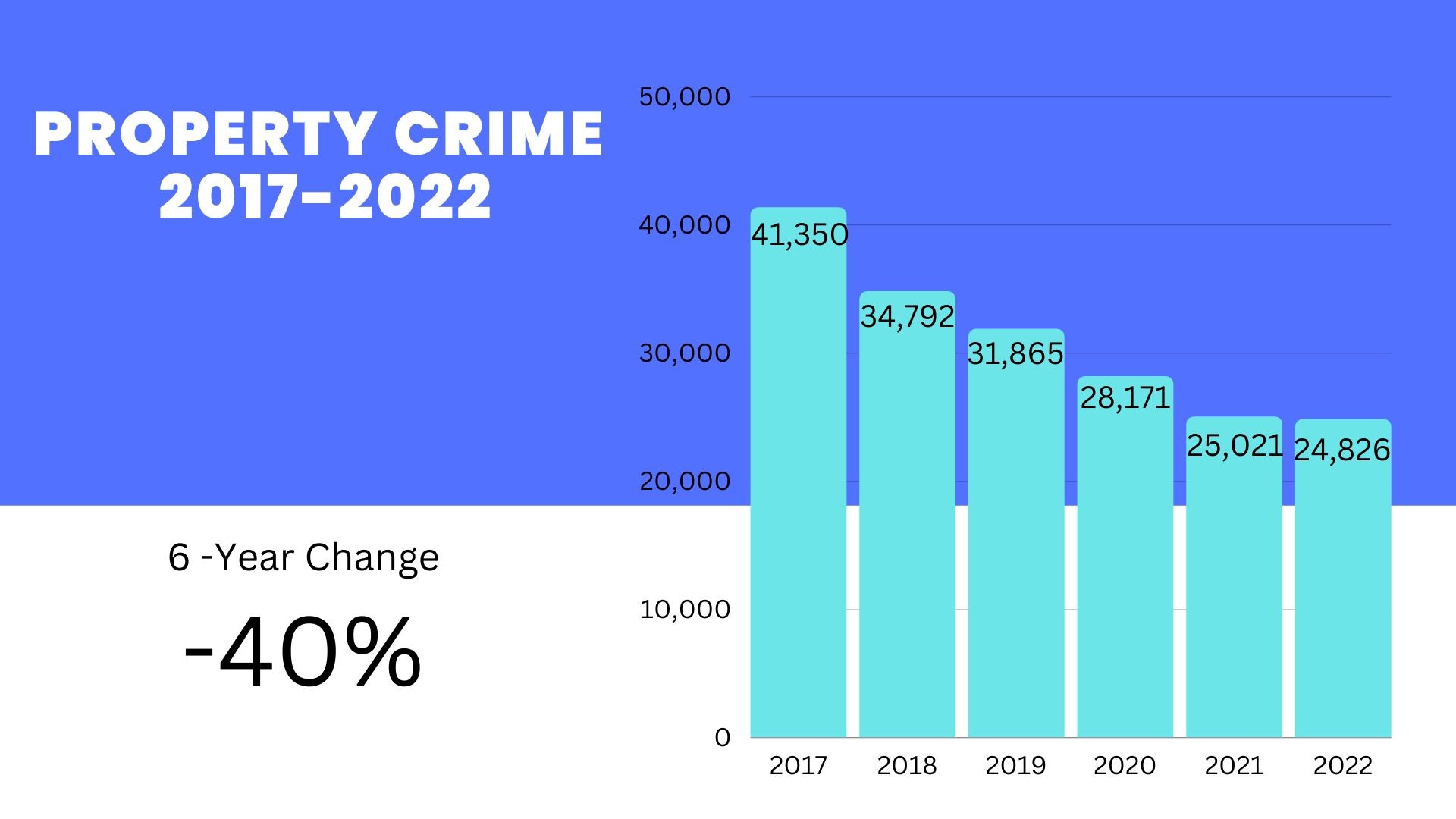

- The "Retail Theft" Illusion: You see videos of shoplifting daily. It feels like violent crime is up. But shoplifting isn't a violent crime. It’s a property crime. They are tracked separately for a reason.

- The Big City Myth: Many people think big cities are inherently more dangerous. While the volume of crime is higher because there are more people, the rate of crime per 1,000 residents is often higher in smaller, rural towns struggling with the opioid crisis.

- The Immigrant Correlation: Study after study, including research from the Cato Institute, shows that immigrant populations (both legal and undocumented) actually have lower crime rates than native-born citizens. The data just doesn't support the "border-driven crime wave" narrative that often pops up in election years.

How Economic Factors Move the Needle

Inflation sucks. We all know it. But does it cause violent crime?

Sorta. It’s indirect.

High inflation and economic instability tend to correlate more with property crime (theft, burglary) than violent crime. However, when communities lose funding for youth programs, or when the "unemployment gap" between demographics widens, the social fabric thins. That's when you see the violent crime by year stats start to creep up. It’s about "collective efficacy"—the fancy term sociologists use for how much neighbors look out for each other. When people are stressed about rent, they look out for each other less.

Actionable Steps: How to Actually Track Safety

If you want to know what’s really going on with violent crime by year without the political spin, you have to do a little homework. Don't just trust a headline.

✨ Don't miss: Why the 2013 Moore Oklahoma Tornado Changed Everything We Knew About Survival

First, check the Council on Criminal Justice (CCJ) reports. They release quarterly updates that are much faster than the FBI. They look at 30+ major cities and give you a real-time pulse of what’s happening. It’s the closest thing we have to a "weather report" for safety.

Second, look at your local police department's "Transparency Portal." Most mid-to-large cities now have a dashboard. You can see exactly how many incidents happened in your precinct last month compared to last year. This is way more useful for your daily life than national averages. National averages are like knowing the average temperature of the entire United States—it doesn't tell you if you need a coat in Seattle.

Third, distinguish between "fear" and "risk." Use the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) National Crime Victimization Survey. This is different from police reports. It asks thousands of regular people if they’ve been victims of a crime. This captures all the stuff that people never even reported to the cops. It gives a much fuller picture of the "dark figure of crime."

Stay informed, but don't stay terrified. The long-term trend of violent crime by year shows that we are, in a broad historical sense, significantly safer than our parents were in the 70s, 80s, and early 90s. The spikes are real, and they are tragic, but they are often the exception, not the new rule.

To keep yourself and your community safe, focus on local involvement. Data shows that neighborhoods with high "civic engagement"—people who show up to town halls, run community gardens, or just know their neighbors' names—have lower violent crime rates regardless of what the national trend is doing. Safety is local. Always has been.