They didn't all head for the woods of British Columbia. That’s the first thing you have to realize. When we talk about Vietnam War draft evaders, the image that pops into most heads is a long-haired college kid burning a card in a park or hitchhiking across the Rainy River. It makes for a great movie scene. But the reality? It was way messier, way more diverse, and honestly, a lot more legally complicated than just running away.

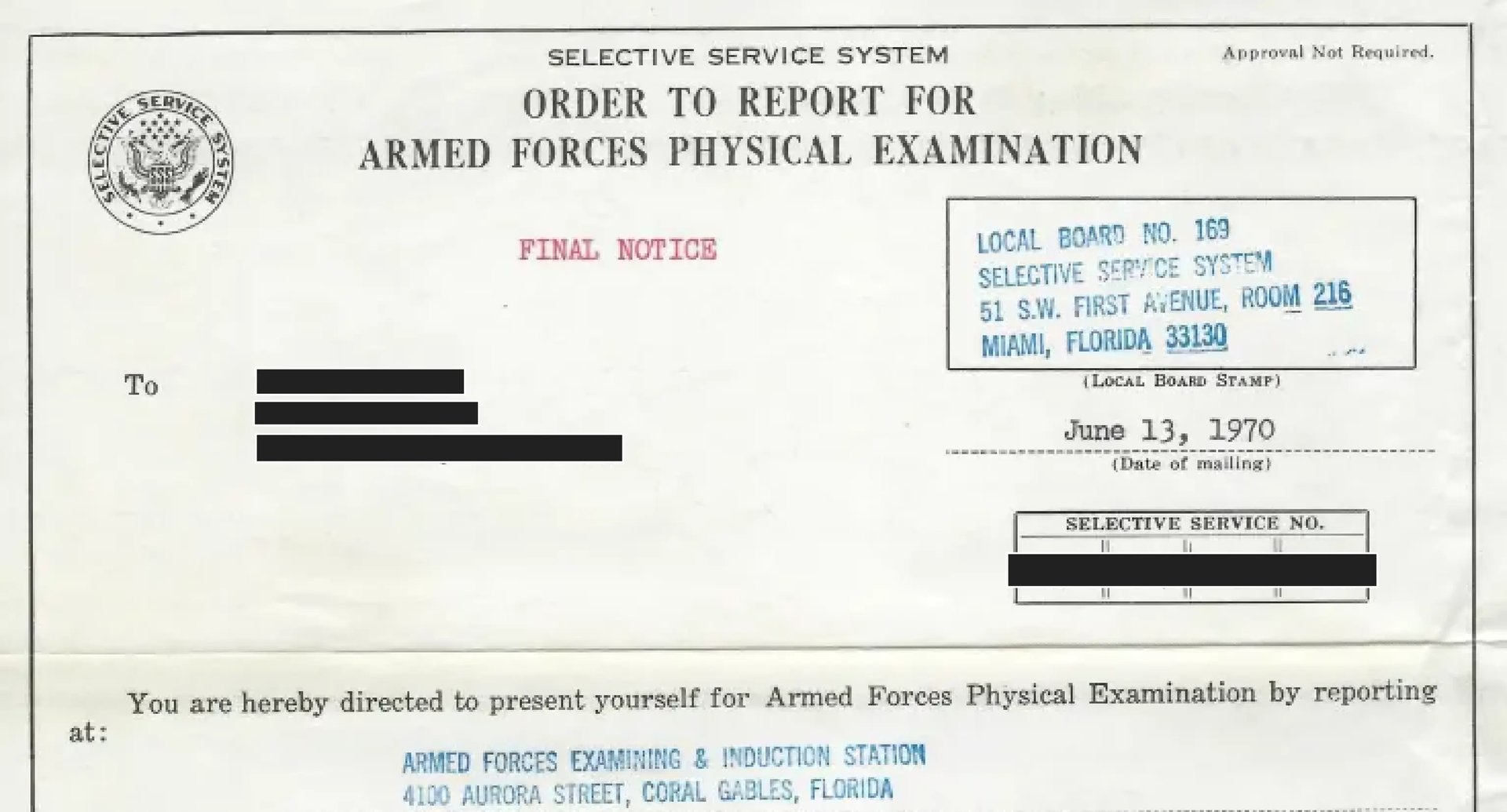

The draft was a giant, creaking machine. Between 1964 and 1973, the Selective Service System inducted about 2.2 million men. But millions more found ways around it. We aren't just talking about "dodgers" who fled the country. We're talking about guys who stayed home and fought the system from the inside, often using the very rules the government wrote.

The Legal Maze of Saying No

Getting out of the draft wasn't always a crime. Actually, for a lot of guys, it was about finding a loophole big enough to walk through.

You had the conscientious objectors (COs). These were the people who, for religious or moral reasons, simply couldn't kill. At first, you had to belong to a "peace church" like the Quakers or Mennonites to even have a shot. But then things changed. In 1970, the Supreme Court weighed in with Welsh v. United States. The Court basically said you didn't need to believe in a traditional God to be a CO; your beliefs just had to be deeply held and moral in nature.

Suddenly, the floodgates opened.

But it wasn't easy. You had to go before a local draft board—usually a group of older, conservative men in your hometown—and prove you weren't just scared. They would grill you. They’d ask, "What would you do if someone attacked your mother?" If you hesitated, you were headed to basic training.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Then there were the deferments. College was the big one. If you could afford tuition, you could stay in school. This created a massive class divide. It meant the front lines were disproportionately filled by working-class guys and people of color who couldn't afford a four-year degree. By the time the government switched to the lottery system in 1969 to try and make it "fair," the damage to the social fabric was already done.

The Canadian Connection and Beyond

Okay, let's talk about the ones who actually left. Estimates vary, but most historians, including experts like Jessica Squires, suggest around 30,000 to 40,000 people went to Canada.

It wasn't a vacation.

Canada didn't officially welcome them with open arms at first. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau eventually said Canada "should be a refuge from militarism," but the border was a roll of the dice. Some guards let you through; others didn't. Once there, these Vietnam War draft evaders had to find jobs without proper papers. They lived in communal houses in Toronto or Vancouver. They were homesick. They missed their parents. They missed Thanksgiving.

And it wasn't just Canada. Some went to Sweden. A few ended up in Mexico.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

What's wild is that the military itself had a massive problem with "evasion" that we now call desertion. There is a huge distinction here. A draft evader is someone who refuses to be inducted. A deserter is someone who is already in the military and leaves. By the end of the war, the desertion rate was staggering. Thousands of GIs just walked away from their posts, often while stationed in Europe or even during R&R in places like Tokyo.

The Myth of the "Rich Kid" Dodger

While it’s true that wealth helped—think of the "bone spurs" or the sudden interest in the National Guard—not everyone who avoided the draft was a privileged elite.

Many were activists. Take the "Oakland Seven" or the guys involved in the "The Catonsville Nine." These weren't people trying to save their own skins; they were trying to break the machine. They raided draft boards and poured animal blood on files. They wanted to make it impossible for the system to function. For them, evading the draft was a political statement, a way to throw a wrench into what they saw as an immoral war.

The Hard Road Back: Amnesty and Scars

The war ended, but the legal limbo didn't.

If you had fled to Canada, you couldn't just come home for Christmas. You faced prison time. It took years of political bickering to figure out what to do with these men.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

- President Gerald Ford tried a "clemency" program in 1974. It was kind of a flop. You had to work a period of alternative service, and many evaders felt they shouldn't have to apologize for being right about the war.

- President Jimmy Carter went bigger. On his first full day in office in 1977, he issued a blanket pardon for most draft evaders.

It was a huge moment. It allowed thousands of men to come home. But—and this is a big "but"—it didn't include deserters. If you had joined the Army and then left, you were still a criminal in the eyes of the law. This created a lasting bitterness. The guy who never went was forgiven, but the guy who went, saw the horror, and then couldn't take it anymore was still a felon.

Why it Still Stings

Even now, decades later, the topic of Vietnam War draft evaders starts arguments. You see it in veterans' halls and at family reunions.

To some, these men were cowards who let others die in their place. They see the 58,000 names on The Wall in D.C. and feel a deep sense of betrayal. To others, the evaders were the moral conscience of a generation. They argue that by refusing to fight in a war based on lies—like the Gulf of Tonkin incident—they were being the ultimate patriots.

The truth is usually somewhere in the middle. Most of these guys weren't trying to be heroes or villains. They were just 19-year-olds caught between a government that wanted them to kill and a conscience that told them not to.

The legacy of this era changed how the U.S. does war. It’s why we have an all-volunteer force today. The government realized that a conscripted army that doesn't want to be there is a liability. They learned that if you force people to fight a war they don't believe in, the system eventually breaks.

Actionable Insights for Researching Ancestry or History

If you’re looking into a family member who might have been a draft evader, or you're just a history buff, here is how you actually find the real stories:

- Check the National Archives: You can request Selective Service records, but keep in mind that many records from the Vietnam era are still being digitized or have privacy restrictions. You usually need the person's consent if they are still living.

- Look for "Other Than Honorable" Discharges: For those who were in the military and left (deserters), their records won't show up in draft evasion databases. They will show up in military personnel files.

- Search Canadian Newspaper Archives: Small-town papers in Ontario and BC often ran stories about "American newcomers" in the late 60s and early 70s. These are goldmines for personal narratives.

- Distinguish between "Draft Dodger" and "Draft Evader": In legal terms, "evasion" is the broad category. "Dodging" is the slang. When searching legal databases like LexisNexis, use the term "Selective Service Act violations" to find actual court cases.

The story of the draft is the story of a divided America. It wasn't just about a war in Southeast Asia; it was about who we are as a country and what a citizen owes the state. Whether you see them as protesters or fugitives, those who said "no" changed the course of American history just as much as those who went.