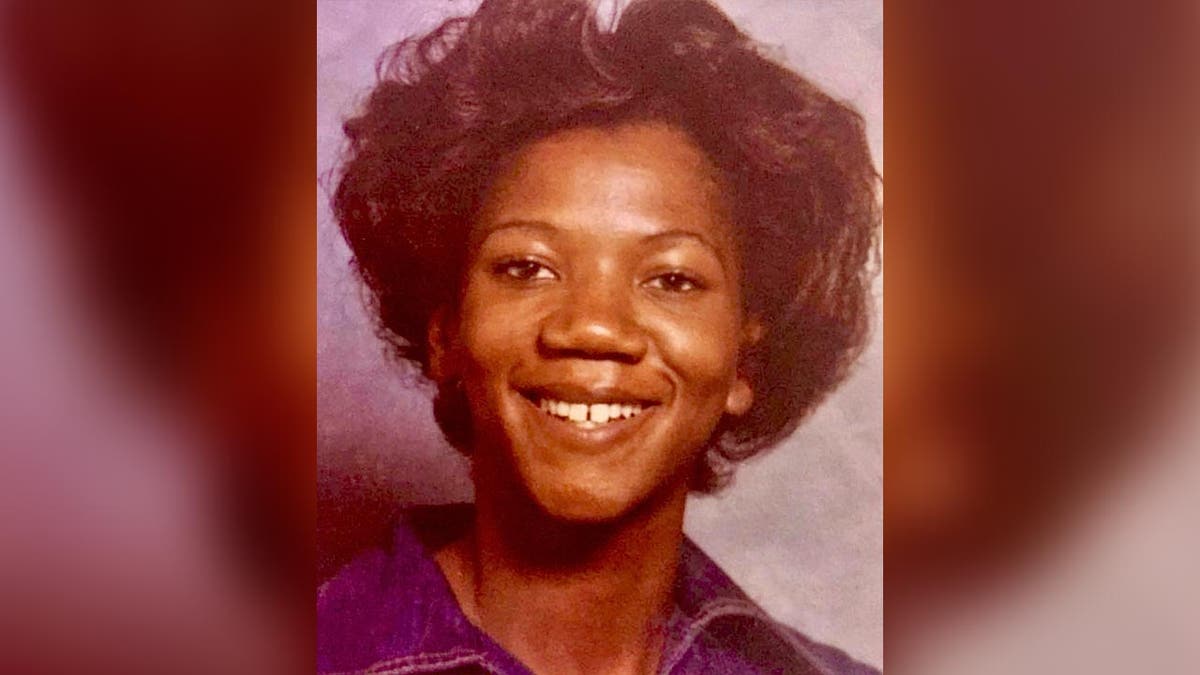

It was September 17, 1984. A Monday. In the Flowing Wells neighborhood of Tucson, Arizona, life felt safe enough that an eight-year-old girl could ride her bike a few blocks away to mail a birthday card. Vicki Lynne Hoskinson did exactly that. She hopped on her bright pink bicycle to send a card to her aunt, a simple errand that should have taken ten minutes.

She never came back.

Her mother, Debbie Carlson, felt that sinking pit in her stomach when twenty minutes passed without Vicki’s return. She sent Vicki’s older sister, Stephanie, to look for her. What Stephanie found changed the family forever: Vicki’s bike was just lying on the side of the road, abandoned. No Vicki. No struggle marks. Just a pink bike in the dirt.

The Man in the Datsun 280Z

Honestly, the way they caught the guy is kinda wild. It wasn't high-tech DNA or a tip from a secret informant. It was a teacher named Sam Hall. He was at the local elementary school that afternoon and saw a suspicious-looking guy in a dark Datsun 280Z with California plates. The driver was acting weird, making "obscene gestures," and struggling with the car's gearshift.

Hall had a gut feeling. He actually ran to his car, grabbed a notepad, and scribbled down the license plate.

🔗 Read more: The Brutal Reality of the Russian Mail Order Bride Locked in Basement Headlines

That single act of intuition broke the Vicki Lynne Hoskinson case. When the plate was run, it came back to Frank Jarvis Atwood. He was 28, a drifter, and—as it turned out—a convicted child molester out on parole from California.

Atwood was already long gone by the time the cops knew his name. He had fled to Texas. But his own parents basically turned him in. When he called them from a mechanic shop in Kerrville, Texas, asking for money to fix his car, his father (a retired brigadier general) took the address and called the FBI.

Seven Months of Agony

For seven months, nobody knew where Vicki was. Atwood was arrested in Texas just days after the disappearance, but he wasn't talking. Well, he was talking, but he was lying. He claimed he was in the area to buy drugs and had gotten into a fight with a dealer, which explained the blood seen on his hands and clothes by his traveling companion, James McDonald.

The search for Vicki was massive. It was the largest in Tucson's history at the time.

💡 You might also like: The Battle of the Chesapeake: Why Washington Should Have Lost

Then came April 12, 1985. A hiker in the Tucson Mountains, about 20 miles from where Vicki vanished, found a small skull. It was Vicki. Because the remains were skeletal after months in the desert, the medical examiner couldn't even determine the exact cause of death. But the location and the context were enough. Atwood was charged with first-degree murder.

The Evidence That Stuck

The trial was a circus of forensic detail. Investigators found pink paint on the front bumper of Atwood's Datsun. It matched the paint from Vicki’s bike perfectly. They also found nickel particles on the car that matched the bike’s handlebars. Basically, the theory was that Atwood had struck the bike with his car to knock her down before snatching her.

The Long Road to June 8, 2022

You’ve gotta realize that this case dragged on for nearly forty years. Atwood was a master of the appeals process. He spent 35 years on death row, maintaining his innocence and claiming the evidence was planted. He even tried to use his degenerative spinal condition as a reason to avoid execution, arguing that being strapped to a gurney would be "cruel and unusual punishment" because of his back pain.

The legal battles went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

📖 Related: Texas Flash Floods: What Really Happens When a Summer Camp Underwater Becomes the Story

On June 8, 2022, justice finally arrived, though many would say it was far too late. Frank Atwood was executed by lethal injection at the state prison in Florence, Arizona. In a surreal twist, because the executioners couldn't find a vein in his arm, Atwood actually helped them, suggesting they try his right hand instead. He died at 10:16 a.m.

Why This Case Still Matters

The Vicki Lynne Hoskinson case didn't just end with a conviction. It fundamentally changed how Tucson—and the rest of the country—viewed child safety. Before Vicki, the "buddy system" was a suggestion; afterward, it became a rule for many families.

Her mother, Debbie Carlson, became a fierce advocate for victims' rights. She helped found the "Victims for Victims" group in Tucson. Her work was instrumental in passing the Arizona Victims' Bill of Rights, ensuring that families of victims have a voice in the courtroom and aren't sidelined by the legal system.

Actionable Insights for Child Safety Today

While the world is different now, the lessons from 1984 remain incredibly relevant.

- Trust Your Gut: Just like Sam Hall, if you see a vehicle or individual acting strangely around schools or parks, document the details. A license plate and a description are better than a vague memory.

- The Power of Advocacy: If you are a victim of a crime or a family member of one, look into local victims' rights organizations. Arizona's laws changed because one mother refused to be quiet.

- Stay Informed on Parolees: In many states, you can search public registries for sex offenders living in your zip code. It's not about living in fear; it's about being aware of your surroundings.

Vicki Lynne’s story is a heartbreaking reminder of how quickly a life can be stolen, but the resilience of her family ensured that her name would be remembered for the lives she protected through legislative change, rather than just the tragedy that took her own.