Square footage is a liar. You walk into a 200-square-foot shell and think, "Yeah, I can fit a range, a prep table, and a reach-in here." Then reality hits. Most people screw up very small restaurant kitchen design because they treat it like a Tetris game instead of a fluid dance. If your chef has to do a 360-degree spin every time they need a garnish, you’ve already lost the labor cost battle.

Small kitchens are high-stakes. Honestly, they’re basically engine rooms. When things get tight, every inch of stainless steel has to justify its existence or get ripped out.

The vertical trap and why you're ignoring your ceiling

Most owners stare at the floor. That's mistake number one. In a cramped space, your floor is for feet; your walls are for everything else. Look at any high-volume ramen shop in Tokyo or a hole-in-the-wall in Manhattan. They don't use floor-standing shelving if they can help it. They use wall-mounted cantilevered shelves that go all the way to the ceiling.

You’ve got to think about the "reach zone." Items used every thirty seconds—like salt, oil, or tasting spoons—stay at eye level. The stuff you use once a shift, like the heavy stock pots or the backup flour, goes up high. If you aren't using magnetic knife strips or hanging pot racks, you're burning money on square footage you don't actually have.

But there’s a catch. Health codes in many jurisdictions, like under the FDA Food Code guidelines often adopted by local boards, require specific clearances. You can't just pile boxes to the rafters. Fire suppression systems (like your Ansul system) need to be able to actually reach the equipment. If your shelving blocks the spray path of a nozzle, you won’t pass inspection. It’s a delicate balance between density and safety.

Very small restaurant kitchen design is about the "pivot"

Movement is the enemy of speed. In a massive hotel kitchen, "walking" is part of the job. In a tiny footprint, walking is a failure of design. You want your line cooks to be able to reach 80% of what they need by simply pivoting on one foot.

Consider the "Work Triangle," a concept famously used in residential architecture but perfected by efficiency experts like those at the Cornell University School of Hotel Administration. In a small commercial setting, this triangle shrinks until it's almost a single point.

The ergonomics of the line

If you’re running a burger joint, the patty shouldn't be more than an arm’s length from the grill. The buns shouldn't require a walk to the other side of the room. It sounds obvious, right? Yet, I’ve seen dozens of builds where the low-boy refrigerator opens the wrong way, forcing a cook to step back and walk around the door just to grab a slice of cheese.

Check your door swings. Seriously. If two doors (like a walk-in and a prep fridge) collide when opened simultaneously, your kitchen will grind to a halt during the Friday night rush. Some designers swear by sliding doors for reach-ins in tight quarters, though they can be a pain to keep on the tracks.

Multi-functional gear is your only savior

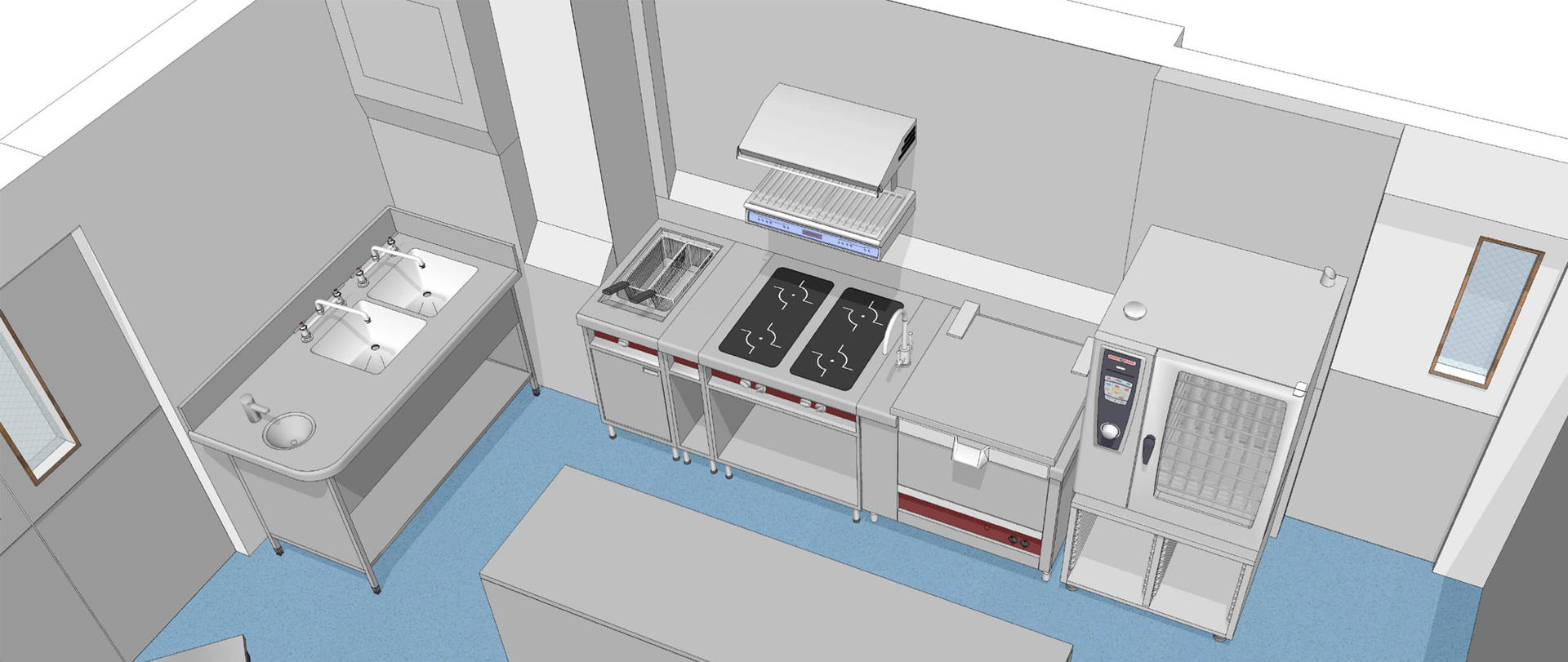

You cannot afford "unitaskers." If a piece of equipment only does one thing, it better do it exceptionally well or it doesn't belong in a very small restaurant kitchen design.

Take the combi-oven. Brands like Rational or Alto-Shaam have become the darlings of the small kitchen world for a reason. They steam, they roast, they bake, and they do it in a footprint smaller than a standard range. You’re paying a premium—sometimes $15,000 to $20,000—but you’re essentially replacing three different appliances.

- Induction burners: These are game-changers. They don't throw off ambient heat. In a 100-square-foot kitchen, a gas range will turn the room into a sauna in minutes. Induction keeps the air cooler, which means your HVAC doesn't have to work as hard, and your staff won't quit due to heat exhaustion.

- Prep-top refrigeration: Don't just get a fridge. Get a fridge with a workspace on top and an integrated rail for containers.

- The "Speed Oven": Think TurboChef or Merrychef. They use a mix of convection and microwave tech to cook things in seconds. If you're doing high-volume toasted sandwiches or quick appetizers, these are worth their weight in gold because they often don't require a Type I hood (depending on what you're cooking).

The invisible monster: Ventilation and Grease

Ventilation is the most expensive part of your build. Period. A standard Type I hood (for grease-laden vapors) can cost $1,000 per linear foot just for the stainless steel, not even counting the makeup air unit or the ductwork.

In a very small space, the "hood footprint" dictates everything. You have to cluster all your heat-producing equipment under that one canopy. If you can move to ventless equipment, do it. Modern ventless fryers and ovens use internal filtration systems that can save you $30,000 in ductwork installation. However, always check with your local fire marshal first. Some cities are still skeptical of ventless tech despite the UL listings.

Drainage is another silent killer. You need floor sinks. You need grease traps. If you’re in an old building, the plumbing is probably shot. Retrofitting a grease interceptor into a tiny basement or under a sink takes up space you don't have. Don't sign a lease until you know exactly where those pipes are going.

Shared spaces and the "Ghost Kitchen" influence

We’re seeing a shift toward "modular" prep. Since you can't fit four people in a tiny kitchen, many owners are moving prep to off-peak hours. One person comes in at 6:00 AM, does all the chopping and portioning, and clears out before the service crew arrives.

This requires a different kind of storage logic. You need "speed racks" that can be tucked away. You need prep tables that fold down or roll on heavy-duty casters. Everything—and I mean everything—should be on wheels. If you can’t move a table to sweep under it or to rearrange the room for a catering order, your kitchen is stagnant.

👉 See also: Euro Money in US Dollars Explained: What You’re Probably Missing

Real talk about the "Dish Pit"

Everyone forgets the dishwasher. They focus on the shiny espresso machine or the wood-fired oven and then realize they have nowhere to put dirty plates.

The dish pit is usually the first place where a small kitchen breaks down. If the "dirty" side of the sink overflows into the "clean" prep area, you've got a cross-contamination nightmare. In a very small restaurant kitchen design, look at high-speed, under-counter glass washers or small-scale upright machines that can cycle in 90 seconds.

You also need a "drying plan." Wet plates take up space. Wall-mounted drying racks that drip directly into the sink are the only way to go. Otherwise, you’ll have stacks of wet trays cluttering your precious counter space.

Specific actionable steps for your layout

Don't just start drawing boxes. Start with the menu. Your menu dictates the equipment, and the equipment dictates the gas lines, water lines, and electrical outlets. If you're only serving cold sandwiches, you don't need a $40,000 ventilation system.

- Map the "Mise en Place": For every menu item, list every ingredient. Where does it live? How far does the cook move to get it? If they have to cross a "traffic lane" to get a garnish, fix the layout.

- Go Ventless Where Possible: Look into EPA 202 test results for ventless equipment. If you can skip the hood, you save tens of thousands in both CAPEX and monthly utility bills.

- Tape it Out: Use blue painter's tape on a floor. Physically stand in the "kitchen" and mimic the motions of making your most complex dish. Do you hit your elbows? Do you trip?

- Electric vs. Gas: In tiny spaces, electric is often better. It’s easier to move, easier to clean, and doesn't add as much heat to the room. Plus, with the 2026 push toward electrification in many urban centers, it's a future-proof move.

- Standardize Your Containers: Use only square Cambros. Round containers waste 25% of the space on a shelf. It sounds nitpicky until you’re trying to fit a week's worth of sauce into a reach-in.

The reality is that a small kitchen forces you to be a better operator. You have to be cleaner. You have to be faster. You have to be more organized. If you can master the flow in 150 square feet, you’ll be unstoppable when you finally upgrade to 1,000.

Focus on the pivot, invest in verticality, and never—ever—underestimate the amount of space you need for dirty dishes. Keep the menu tight, keep the equipment multi-functional, and ensure every square inch earns its rent. That is how you win the small-footprint game.