It was supposed to be the crown jewel of the Gulf Coast’s transition to clean energy. When Vertex Energy bought the Mobile refinery from Shell for $75 million back in 2022, the markets went wild. You could practically hear the collective sigh of relief from investors who thought they’d finally found a traditional oil player with the guts to go full "green." The plan was ambitious. They weren’t just going to refine crude; they were going to turn soybean oil and waste fats into renewable diesel.

But then, things got messy.

If you’ve been following the energy sector lately, you know that the "green premium" is a fickle beast. Vertex Energy’s journey with the Mobile refinery is a case study in what happens when high-interest rates, volatile feedstock prices, and the brutal reality of refining margins collide. It’s not just a story about a factory in Saraland, Alabama. It’s a story about the survival of small-cap energy companies in an era where the rules change every single week.

The Shell Exit and the Birth of a New Mobile Refinery

Shell wanted out. That’s the part people forget. Large integrated oil companies were shedding "non-core assets" faster than a snake sheds skin in 2021 and 2022. The Mobile refinery, situated right on the edge of the Chickasaw River, was a reliable asset, but it didn't fit Shell’s massive global carbon-neutrality roadmap. Vertex stepped in.

They saw potential where others saw a legacy burden.

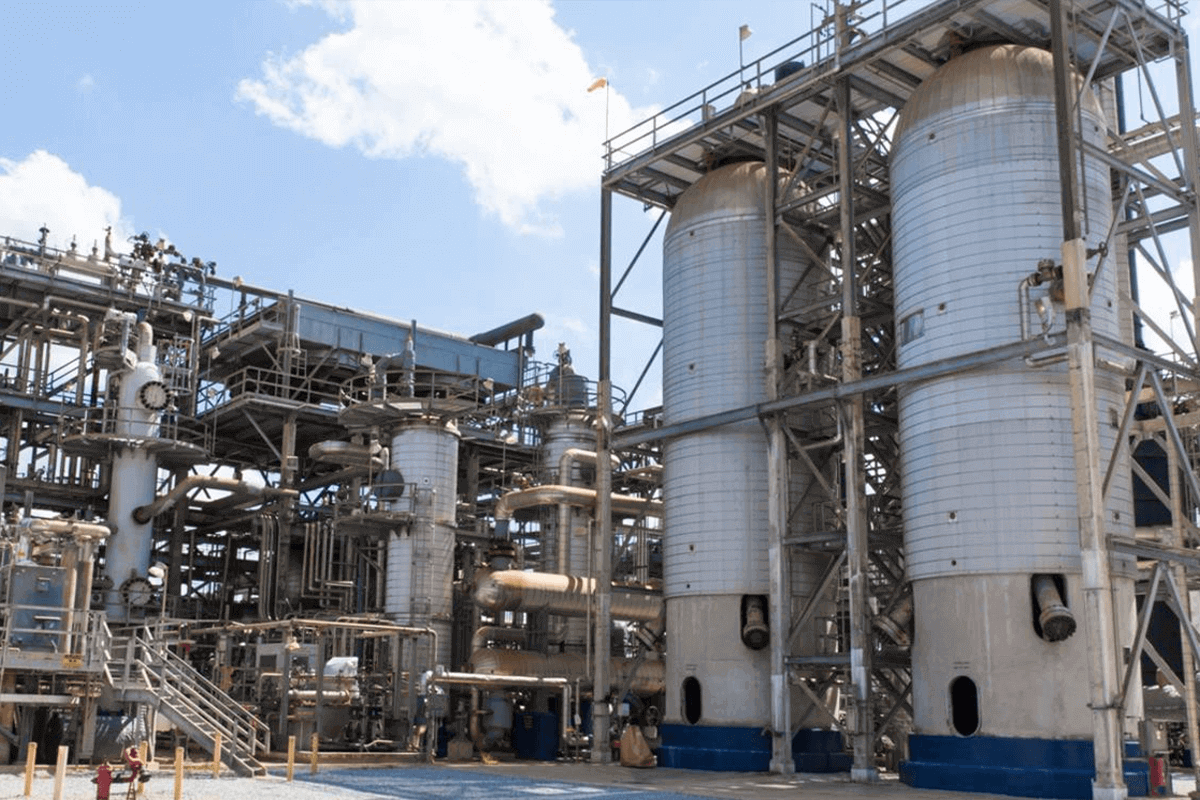

By acquiring the site, Vertex didn't just get some pipes and tanks. They got a strategic location with a high-capacity hydrocracker. To the uninitiated, a hydrocracker is basically the "brain" of a refinery. It uses high pressure and hydrogen to break down heavy molecules into lighter, more valuable products like jet fuel and diesel. Vertex realized that with a few hundred million dollars in upgrades, they could pivot this machine toward renewable feedstock.

It was a bold move. Maybe too bold for the timing.

The Renewable Diesel Pivot: Why It Slipped

The core of the Vertex Energy Mobile refinery strategy was the "Phase 1" conversion. They spent roughly $115 million to modify that hydrocracker. The goal? Produce about 8,000 to 10,000 barrels per day (bpd) of renewable diesel. For a second, it looked like it was working. By mid-2023, they were actually pumping the stuff out.

But then the math stopped mathing.

You see, renewable diesel depends on something called "feedstock." Usually, this is soybean oil, corn oil, or used cooking oil (the stuff people call "UCO"). In 2023 and early 2024, the price of these fats stayed stubbornly high while the "crack spread"—the profit margin for refining—started to shrink. Honestly, the market got flooded. Too many players jumped into renewable diesel at the same time, and suddenly, that "green gold" felt more like a lead weight.

👉 See also: Facebook Business Support Chat: Why You Can't Find It and How to Actually Get Help

Vertex had to make a painful choice.

In May 2024, they dropped a bombshell. They were pivoting back. Well, "re-optimizing" is the corporate word they used. Basically, they decided to stop focusing so hard on renewable diesel and move the hydrocracker back toward conventional fuels. Why? Because the money was in fossil fuels again. The margins on conventional diesel and jet fuel were simply better than the subsidized, but expensive-to-make, renewable stuff.

What People Get Wrong About the Mobile Refinery Debt

If you read the headlines, you'd think Vertex was underwater solely because of the refinery’s tech. That’s not the whole truth. It was the debt structure.

To buy the Mobile refinery, Vertex took on some heavy-hitting loans. We’re talking about interest rates that would make a credit card holder wince. When the Federal Reserve started hiking rates, the cost of servicing that debt ballooned. It’s one thing to run a refinery when you’re flush with cash; it’s another thing entirely when your lenders are breathing down your neck every quarter.

The Realities of Saraland Operations

The site itself is a beast.

- It covers hundreds of acres.

- It has a total capacity of around 75,000 barrels per day.

- It employs hundreds of local Alabamians who have worked those units for decades.

When a company like Vertex struggles, it’s not just a ticker symbol moving on a screen in Manhattan. It’s a community in Saraland wondering if the flares will stay lit. The shift back to conventional refining was actually a move to save those jobs. By focusing on what the refinery was originally built for—processing various grades of crude—they sought to stabilize the cash flow.

The Chapter 11 Filing: A Necessary Reset?

In September 2024, the shoe finally dropped. Vertex Energy filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

Wait. Don’t assume that means the refinery is closing.

In the energy world, Chapter 11 is often just a very expensive, very legal way of telling your lenders, "We need to talk." Vertex entered into a "stalking horse" agreement to sell the Mobile refinery. The goal was to wipe out the debt and find a buyer with deeper pockets—someone who could weather the storm of volatile oil prices without worrying about the next interest payment.

✨ Don't miss: Why 444 West Lake Chicago Actually Changed the Riverfront Skyline

During this whole process, the refinery has kept running. That’s the crazy part. Most people think a bankruptcy means the lights go out. In reality, the Mobile refinery continued to process crude, ship fuel to the Southeast, and keep its staff on the payroll. It’s a "debtors-in-possession" situation where the operations are actually the most valuable thing the company owns.

Why This Matters for the Future of US Energy

The Vertex Energy Mobile refinery saga is a warning. It’s a warning that the energy transition isn’t going to be a straight line. It’s going to be jagged.

We need these mid-sized refineries. Without them, the supply chain for gasoline and diesel in the Southern United States gets incredibly brittle. If the Mobile site were to shut down permanently, fuel prices across Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida would likely see a noticeable spike.

Also, it highlights the "Scale Problem."

- Large companies like ExxonMobil or Valero can afford to lose money on a green project for years.

- Small companies like Vertex have zero margin for error.

- When the government changes a tax credit or a "RVO" (Renewable Volume Obligation) mandate, the small guys feel the punch immediately.

Vertex tried to do something extremely difficult: they tried to be the small, agile pioneer in a world built for giants. They succeeded in the engineering, but they got caught in the economic crossfire.

Analyzing the Buyout Potential

So, who wants a 75,000 bpd refinery in Alabama?

Actually, quite a few people. Private equity firms often look at "distressed assets" like this and see a bargain. If you can buy a refinery for a fraction of its replacement cost and you don't have the baggage of the old debt, you can make a killing. There’s also the possibility of a larger independent refiner stepping in.

The Mobile refinery is a "complex" site. It’s not a simple teapot refinery. It can handle different types of crude oil, which is a massive advantage when global shipping routes are a mess. Whether it’s Brent, WTI, or something heavier, the Mobile units can generally handle the diet.

The Operational Shift: What’s Happening Now

Right now, the focus is back on the basics.

🔗 Read more: Panamanian Balboa to US Dollar Explained: Why Panama Doesn’t Use Its Own Paper Money

The renewable diesel equipment is still there. It’s not like they threw it in the trash. It’s "idled" or "dual-purpose." This means if the market for renewable diesel suddenly rockets back up—say, because of a new carbon tax or a massive jump in government subsidies—the Mobile refinery could, in theory, flip the switch back.

But for today? It’s all about traditional crack spreads. They are looking at the price of a barrel of oil versus the price of the gasoline and diesel they can pull out of it.

What You Should Do If You're Following This Space

If you’re an investor, a local resident, or just an energy nerd, you need to watch the court filings. The "sale process" for the Vertex Energy Mobile refinery will dictate the next decade of energy in that region.

- Watch the "Stalking Horse" Bid: This sets the floor price for the asset. If no one outbids them, the refinery goes to the primary lender or a designated buyer.

- Monitor Feedstock Spreads: If you see the price of soybean oil drop significantly while diesel stays high, that's when the "green" talk will start up again.

- Keep an eye on the RINs market: Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs) are the "currency" of the renewable fuel world. They are notoriously volatile. Vertex’s fortunes have often risen and fallen based on these regulatory credits.

Honestly, the whole situation is a bit of a rollercoaster. You've got a company that tried to do the right thing for the environment, got smacked by the economy, and is now trying to survive through a total restructuring. It’s as "real world" as it gets in the business of energy.

Actionable Insights for the Path Ahead

The story of the Vertex Energy Mobile refinery isn't over, but the lessons are already clear. Here is how you should approach this moving forward:

Evaluate the Asset, Not the Ticker If you are looking at the viability of the refinery, look at its "throughput" and "complexity rating." The hardware at the Mobile site is objectively good. It’s the balance sheet that failed, not the pumps.

Understand the Regional Impact If you live in the Alabama area, recognize that the refinery is a critical infrastructure piece. Its survival is tied to regional energy security. Support for the "re-optimization" back to conventional fuels is, ironically, the most "sustainable" thing for the local economy right now.

Watch for the New Ownership Structure Once the Chapter 11 process concludes, the "new" Mobile refinery will likely emerge with a much leaner cost structure. This "NewCo" will be a formidable competitor in the Gulf Coast market because it won't be carrying the $600+ million in debt that hobbled Vertex.

Diversification is a Double-Edged Sword The biggest takeaway from the Vertex experiment is that diversifying into renewables requires a massive capital cushion. If you're looking at other small-cap energy companies trying to make the "green pivot," check their cash reserves first. If they don't have enough to survive two years of bad margins, they might be the next Vertex.

The Mobile refinery remains a powerhouse of production. Its future might not be as "green" as originally promised three years ago, but in the world of energy, being "profitable" is the only way to stay "available." The pivot back to basics isn't a failure—it's a survival tactic in an unforgiving market.