You're hiking. The sun is beating down on the dusty trail when a flash of scales darts across your path. Your heart does a little jump. Naturally, the first thing you probably think is, "Is that snake poisonous?"

I hate to be the "actually" person, but honestly, you're almost certainly using the wrong word.

✨ Don't miss: Blonde Hair Eyebrow Tint: Why Most People Get the Shade Completely Wrong

It’s a linguistic slip-up that drives herpetologists up the wall. Most snakes aren't poisonous at all. They're venomous. It’s not just about being a pedantic science nerd; knowing the difference between a venomous vs poisonous snake can genuinely change how you handle an encounter in the wild, or at least help you sound like you know what you’re talking about at the next backyard BBQ.

The "Who Bites Whom" Rule

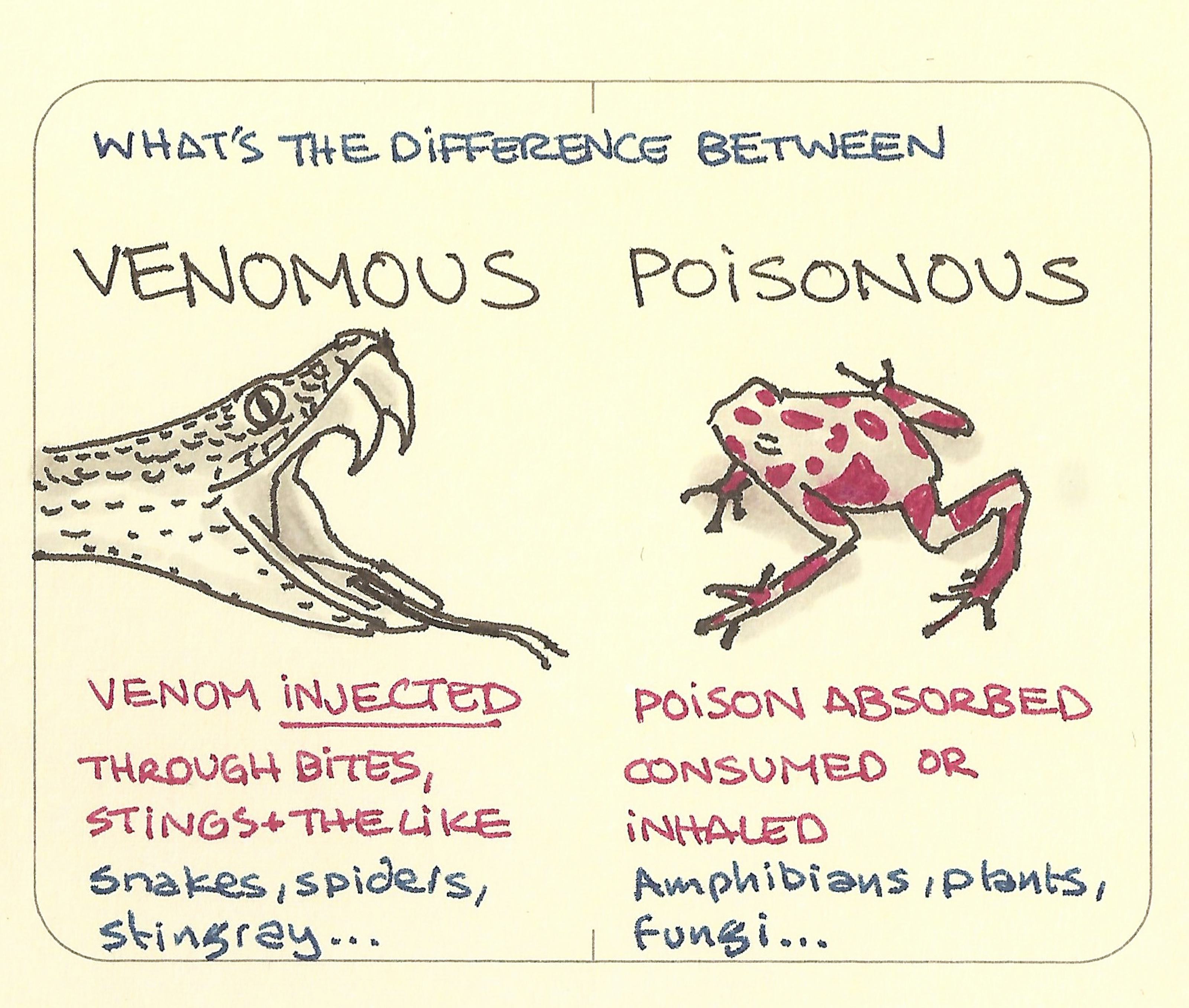

Basically, the distinction comes down to delivery. Biologists have a simple, slightly morbid rhyme to keep it straight: If you bite it and you die, it's poisonous. If it bites you and you die, it's venomous.

Venom is an active delivery system. It’s a specialized saliva, a complex cocktail of proteins and enzymes stored in glands and injected through fangs or teeth. Think of it like a biological syringe. The snake has to do something to you—strike, bite, or in the case of some cobras, spit—to get that toxin into your bloodstream.

Poison, on the other hand, is passive. It’s usually secreted through the skin or stored in the liver or muscles. To get sick from something poisonous, you have to touch it or eat it. If you decided to sauté a dart frog for lunch, you’d be in a world of hurt. But if that same frog hopped across your foot? You'd likely be fine unless you had an open wound.

Why the mix-up happens

It’s easy to see why we get confused. Both involve toxins. Both can be lethal. In common conversation, we use "poisonous" as a catch-all term for "deadly thing that comes from nature." But in the animal kingdom, these two strategies evolved for completely different reasons. Venom is usually for hunting—subduing prey so the snake doesn't have to wrestle a frantic rat. Poison is almost always for defense—making sure a predator regrets its life choices after taking a nibble.

The Weird Exceptions: Snakes That Are Both

Nature loves to make things complicated. Just when you think you’ve mastered the venomous vs poisonous snake distinction, along comes the Rhabdophis genus, specifically the Japanese Grass Snake (Rhabdophis tigrinus).

These guys are absolute overachievers. They have venomous fangs to kill frogs, but they also have "nuchal glands" in their necks. When they eat certain toxic toads, they actually sequester the toad's toxins and store them in those neck glands. If a bird tries to eat the snake, it gets a mouthful of stolen toad poison.

So, yes, it’s a venomous snake that is also poisonous. It’s a double-threat that breaks all the standard rules of biology classes.

📖 Related: Why the FIT Fall 2025 Calendar is Stressing Everyone Out (and How to Fix It)

There’s also the Common Garter Snake. Most people think they're totally harmless. While they are technically mildly venomous (don't worry, it's mostly just itchy for humans), some populations in the Pacific Northwest become poisonous to predators because they eat toxic newts. Their bodies hold onto the toxins, making the snake itself a dangerous meal for a hawk or a crow.

How Venom Actually Works (It’s Not Just One Liquid)

When people talk about venomous snakes, they often treat "venom" as one thing. It's not. It’s a terrifyingly diverse array of chemical weapons.

- Hemotoxins: These go after your blood and tissue. If you get bit by a Rattlesnake or a Copperhead, you’re dealing with hemotoxins. They basically start digesting you from the inside out, breaking down red blood cells and causing massive swelling and internal bleeding. It is excruciating.

- Neurotoxins: These are the "quiet" killers. Found in Cobras, Mambas, and Coral Snakes, neurotoxins attack the nervous system. They block the signals from your brain to your muscles. Eventually, your diaphragm stops moving, and you stop breathing. The scary part? Sometimes there’s very little pain or swelling at the bite site.

- Cytotoxins: These are localized. They destroy cells at the site of the bite. Imagine a chemical burn that just keeps spreading.

The complexity of these toxins is why "all-in-one" antivenom doesn't exist. You can't use King Cobra antivenom to treat a Diamondback Rattlesnake bite. They are fundamentally different chemical formulas.

Identifying the Danger in Your Backyard

In the United States, we’re lucky. We only have two main families of venomous snakes to worry about: Pit Vipers and Elapids.

The Pit Viper Squad

This includes Rattlesnakes, Copperheads, and Cottonmouths (Water Moccasins). They’re called pit vipers because of the heat-sensing pits located between their eyes and nostrils. It’s basically infrared vision.

You’ve probably heard the old wives' tale about "triangular heads" being the mark of a venomous snake. There’s a grain of truth there, but it’s a dangerous rule to rely on. Many non-venomous snakes, like the Hognose or North American Water Snake, will flatten their heads when they feel threatened to look like a viper. It's a bluff. On the flip side, some venomous snakes have slim, oval heads.

The Elapid Exception: The Coral Snake

The Coral Snake is the outlier. It doesn’t have a big, chunky viper head. It’s small, colorful, and looks like a toy. This is where the famous rhyme comes in: "Red touch yellow, kill a fellow; red touch black, friend of Jack." This works in the U.S. for distinguishing Coral snakes from harmless King snakes, but do not use this rhyme in Central or South America. Down there, the patterns vary wildly, and the rhyme could literally get you killed. Honestly? Just don't touch colorful snakes.

The Myth of the "Aggressive" Snake

We need to clear something up. Snakes are not out to get you.

I’ve spent a lot of time around snakes, and the "aggressive" label is almost always a misunderstanding of defensive behavior. A Cottonmouth gaping its white mouth at you isn't trying to hunt you down; it's saying, "Look at my scary fangs, please leave me alone so I don't have to waste my precious venom on something I can't even eat."

Venom is "metabolically expensive." It takes a lot of energy for a snake’s body to produce it. If they use it on you, they might not have enough left to catch the mouse they need for dinner tomorrow. This is why "dry bites" happen. Between 20% and 50% of venomous snake bites in humans contain no venom at all. It’s a warning shot.

What to Do (and Absolutely NOT Do) If Bitten

Forget everything you saw in old Western movies. Seriously.

- Do NOT try to suck out the venom. You aren't John Wayne. You’ll just get venom in your mouth and bacteria in the wound.

- Do NOT use a tourniquet. If it's a hemotoxic bite (like a Rattlesnake), a tourniquet traps all that tissue-destroying venom in one spot. It’s a great way to ensure you lose the entire limb instead of just having a nasty scar.

- Do NOT apply ice. It doesn't help and can actually worsen tissue damage.

- Do NOT try to catch the snake. Medical professionals don't need the snake brought into the ER. They can usually tell what bit you by the symptoms, and trying to catch it just leads to a second person getting bitten.

The only real "cure" for a bite from a venomous snake is a cell phone and a car. Get to a hospital that has antivenom. Keep the bitten limb at or slightly below heart level, stay as calm as possible to keep your heart rate down, and get professional help.

📖 Related: Why 5 times 7 is the weirdest number in basic math

Real World Survival Insights

If you live in an area where snakes are common, your best defense isn't a field guide—it's a pair of boots and a flashlight. Most bites happen because someone stepped on a snake they didn't see or stuck their hand into a dark crevice (like a woodpile or under a rock) where a snake was napping.

Wear thick leather boots when hiking. Use a stick to poke around before you reach into tall grass. Most importantly, respect the distance. Most snakes can strike about half their body length. If you're six feet away, you're generally in the safety zone.

The whole venomous vs poisonous snake debate is more than just a grammar lesson. It’s about understanding the mechanisms of the natural world. Snakes are vital to our ecosystem; they keep rodent populations in check and provide the basis for life-saving medicines (the blood pressure drug Captopril was actually derived from jararaca pit viper venom).

Your Next Steps for Snake Safety

- Audit your yard: Remove piles of debris, tall grass, and rock piles near your house. You aren't just removing snake hiding spots; you're removing the habitat for the mice that snakes like to eat.

- Identify your locals: Look up a "Snakes of [Your State]" guide. Learn the 3 or 4 venomous species in your area so you can recognize them instantly.

- Get the right gear: If you're an avid hiker, invest in snake gaiters. They're lightweight and provide peace of mind in heavy brush.

- Download the "SnakeSnap" app: It’s a great resource for quick identification if you manage to snap a photo from a safe distance.

Stop worrying about being "attacked" and start being aware. A snake is just a hungry tube of muscle trying to survive in a big, scary world. Give them their space, use the right terminology, and you’ll both get home in one piece.