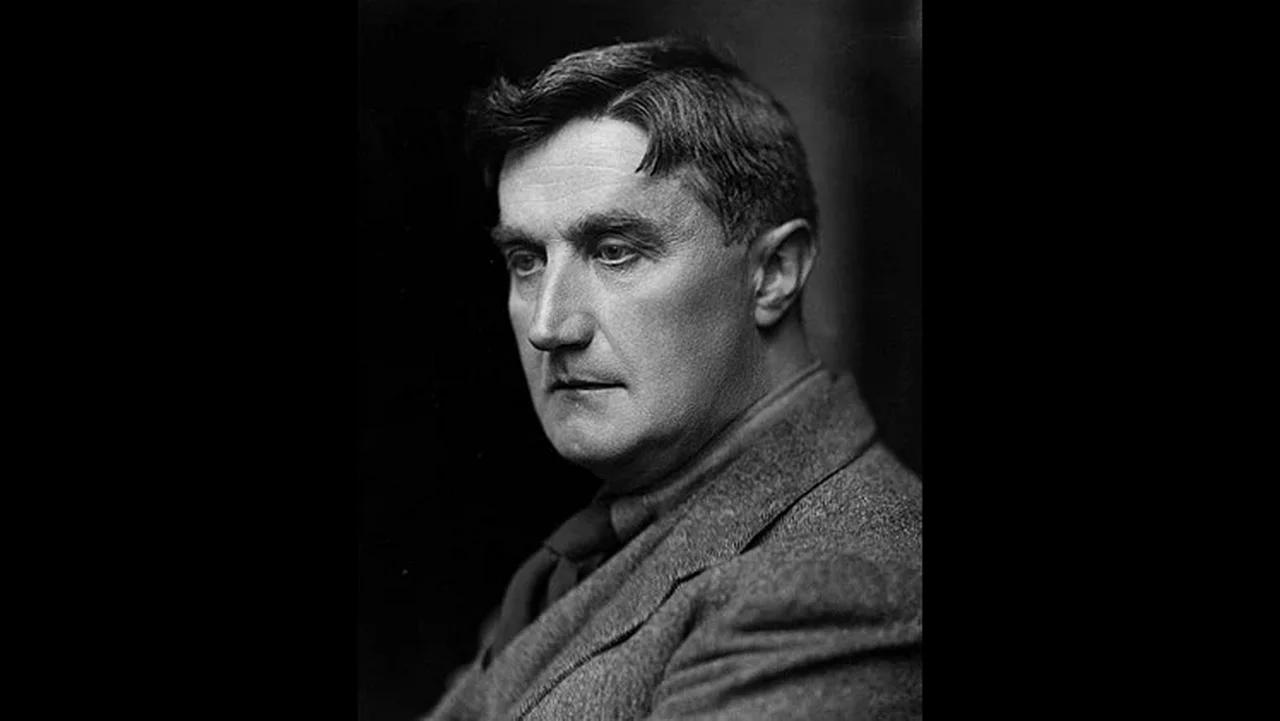

It was 1938. London was nervous. The shadow of another war was stretching across Europe, yet inside the Royal Albert Hall, something remarkably still and beautiful was about to happen. Sir Henry Wood, the legendary conductor who basically built the Proms into what they are today, was celebrating his jubilee—fifty years on the podium. He wanted something special. He didn't want a loud, clashing celebration of his own ego. He asked his friend Ralph Vaughan Williams for a gift. What he got was the Vaughan Williams Serenade to Music, a piece of such ethereal quality that it reportedly left Sergei Rachmaninoff in tears.

Rachmaninoff, sitting in the audience, was so moved by the sheer loveliness of the sound that he admitted he had never heard anything quite like it. It’s easy to see why. Most composers write for a choir as a single block of sound. Vaughan Williams didn't do that. He looked at sixteen of the greatest British singers of the era—stars like Isobel Baillie and Heddle Nash—and he wrote specific lines tailored to their individual voices. He literally put their initials in the score.

Shakespeare, Moonlight, and the Power of Sound

The text isn't some dry, religious hymn. It’s pure Shakespeare. Specifically, it's the "moonlight" scene from Act V of The Merchant of Venice.

"How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank!"

When you hear those opening violin chords, you can almost feel the temperature drop. It’s cool. It’s silvery. The music mimics the rotation of the heavens. Vaughan Williams was obsessed with the idea of the "music of the spheres"—the ancient belief that the planets made a divine sound as they moved.

Most people think of Vaughan Williams as the "folk song guy." You know, the one who walked around the English countryside transcribing tunes from old sailors. While that's true, the Vaughan Williams Serenade to Music shows his other side. This is his sophisticated, luminous side. He takes Shakespeare’s argument—that someone who isn't moved by music is basically untrustworthy—and proves it through harmony.

✨ Don't miss: Why La Mera Mera Radio is Actually Dominating Local Airwaves Right Now

The structure is fluid. It doesn't follow a rigid A-B-A format like a pop song or a standard symphony movement. Instead, it breathes. It expands when the text talks about "the floor of heaven" being "thick inlaid with patines of bright gold," and it shrinks back down to a whisper when discussing the "soft stillness" of the night.

The Logistics of Sixteen Soloists

Honestly, the biggest problem with this piece is the math. Writing for sixteen soloists is a nightmare for modern concert promoters. It’s expensive. You have to hire sixteen high-level professionals, all of whom need to be balanced perfectly.

In the original performance, these weren't just random singers. They were the "Who's Who" of the British vocal scene. Because the piece was so deeply tied to those specific people, some critics initially thought it wouldn't survive them. How do you replace an Isobel Baillie?

Well, Vaughan Williams was practical. He eventually made arrangements for a standard four-part choir and orchestra, and even a purely orchestral version. But let’s be real: those versions are fine, but they don't have the "magic." There is a specific friction and shimmer that happens when sixteen distinct solo voices vibrate against each other. It creates a texture that feels three-dimensional.

Why the Serenade to Music Hits Different Today

We live in a loud world. Everything is compressed. Everything is "content." The Vaughan Williams Serenade to Music is the opposite of that. It requires a certain type of patience.

🔗 Read more: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

One of the most striking moments is the setting of the line, "I am never merry when I hear sweet music." It’s a paradox, right? Why would sweet music make you sad? Vaughan Williams captures that specific "blue" feeling—the melancholy that comes from seeing something so perfect you know it can't last.

Musically, he uses a lot of "false relations." This is a fancy way of saying he plays a natural note and a flattened note almost at the same time or in quick succession. It creates a shimmering, slightly blurred harmonic effect. It’s like looking at a reflection in a pond just as a ripple goes through it. It’s quintessentially English, yet it feels universal.

The Rachmaninoff Connection

It’s worth circling back to Rachmaninoff. He was a man known for his own lush, romantic melodies, but he was also a bit of a grump. He didn't hand out compliments easily. For him to be visibly shaken by the Vaughan Williams Serenade to Music says everything you need to know about the work's emotional weight.

It wasn't just the melody. It was the orchestration. Vaughan Williams used the harp and the solo violin to create a sense of infinite space. When the singers reach the climax—"O hear the music!"—the orchestra doesn't just get louder. It gets wider.

Common Misconceptions

People often mistake this for a religious work because of the "heaven" references. It's not. It’s deeply secular. It’s about the human experience of art.

💡 You might also like: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

Another mistake? Thinking it’s just "pretty." If you listen closely to the middle section, where the text discusses "the man that hath no music in himself," the tone shifts. It gets darker. Grittier. There’s a warning there. The music suggests that a soul without art is "fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils." It’s a brief, sharp reminder that beauty exists in contrast to the darkness of the human heart.

Performing and Listening: What to Look For

If you’re looking for a recording, the original 1938 recording with the original sixteen soloists is essential history, though the audio quality is obviously aged. For a modern crispness, the Matthew Best recording on Hyperion or the Sir Adrian Boult versions are usually the gold standard.

When you listen, pay attention to the transition back to the opening theme at the end. The way the solo violin climbs up into nothingness is one of the most perfect endings in all of classical music. It doesn't "finish" so much as it just evaporates.

How to Truly Experience This Work

To get the most out of the Vaughan Williams Serenade to Music, you have to stop multitasking. This isn't background music for answering emails.

- Find the text first. Read the "Merchant of Venice" passage (Act 5, Scene 1). Understand the context of Lorenzo and Jessica sitting in the garden.

- Listen for the "Initial" solos. If you can find a score or a guided listening note, try to identify when the different soloists take their turns.

- Watch a live performance if possible. Seeing the physical arrangement of sixteen singers across the stage adds a visual layer to the antiphonal effects Vaughan Williams built into the music.

- Focus on the silence. The gaps between the phrases are just as important as the notes themselves.

The Vaughan Williams Serenade to Music remains a testament to a specific moment in time when music was used to stave off the encroaching darkness of the world. It’s a reminder that even when things look grim, there’s a "soft stillness" that we can retreat into, if only for thirteen minutes.

To explore this further, compare this work to Vaughan Williams’ Toward the Unknown Region or Flos Campi. You’ll start to see a pattern in how he uses the human voice not just as an instrument, but as a bridge between the physical world and something much more vast. Look for the 1938 Columbia recording to hear the original "Sixteen"—it's the only way to hear exactly what Wood heard on that historic night.