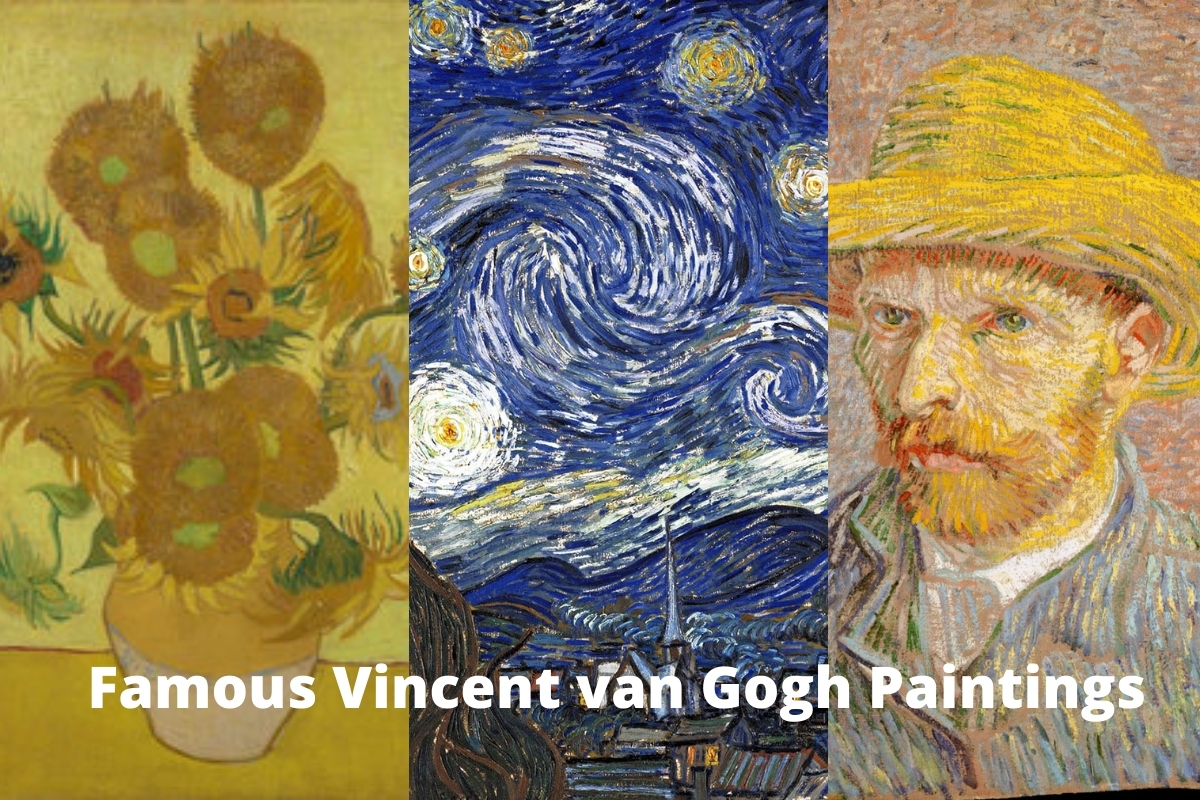

You’ve seen the mugs. You've seen the immersive digital exhibits where the walls "bleed" yellow paint. Honestly, it’s a bit much sometimes. But when you strip away the gift-shop kitsch and actually look at van gogh most famous paintings, there’s a reason they still hit you like a physical weight in the chest. Vincent wasn't just some "tortured artist" archetype that Hollywood dreamed up; he was a guy who was desperately trying to communicate through color because he couldn't quite figure out how to do it with people.

He only painted for about a decade. Think about that. Most artists take ten years just to find a style that doesn't suck. In that tiny window, he churned out over 2,000 works. Most of the stuff we obsess over today—the swirling skies, the heavy impasto, the vibrating yellows—all came from the last two years of his life while he was bouncing between mental breakdowns and a voluntary stay in an asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

The Starry Night is actually a view from a prison cell (basically)

When people talk about van gogh most famous paintings, The Starry Night is the big one. It’s the "Mona Lisa" of the post-impressionist world. But here’s the thing: he painted it from a room with bars on the windows. He wasn't standing in a field under a magical sky. He was in the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum. He wrote to his brother Theo, "This morning I saw the country from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big."

That "morning star" was actually Venus.

The painting is weirdly loud. If you stand in front of it at the MoMA in New York, you realize it isn't "pretty." It’s aggressive. The cypress tree in the foreground looks like a flame, and in the late 1800s, cypress trees were symbols of mourning and death. He was literally painting a bridge between the earth and the sky—between life and whatever comes next. The village at the bottom? He made that up. It’s a mix of the local French scenery and his memories of the Netherlands. He was homesick, lonely, and vibrating with an energy that he couldn't contain.

Why the Sunflowers aren't as bright as they used to be

Most people don't realize that Van Gogh was a bit of a chemistry experimenter, and not always a good one. He loved chrome yellow. It was a new, vibrant pigment at the time. Unfortunately, it’s chemically unstable. Over the last century, many of the van gogh most famous paintings featuring those iconic yellows have started to turn a muddy, olive brown. It’s a literal race against time for conservators at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

👉 See also: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

The Sunflowers series wasn't just one painting. He did a bunch of them. The most famous versions were meant to decorate a bedroom for his friend Paul Gauguin. Vincent wanted to impress him. He wanted to create an artist's colony in the South of France—a "Studio of the South." He was so excited, so hopeful. Then Gauguin showed up, they argued constantly, Vincent cut off a piece of his ear, and the whole dream collapsed.

- The 1888 version (Yellow Background): This is the one everyone knows. It’s yellow on yellow. It breaks all the traditional rules of contrast.

- The 1887 Paris versions: These are different. The flowers are cut and lying on a table, looking a bit more "dead" and realistic.

- The National Gallery version: Often cited as the pinnacle of his color theory work.

He used "impasto," which is just a fancy way of saying he globbed the paint on so thick that it stands off the canvas. You can see the ridges of his brush. You can see where he used a palette knife. It’s tactile. It’s messy. It’s human.

The Bedroom and the crushing reality of loneliness

If you want to understand the man behind van gogh most famous paintings, look at The Bedroom. He painted his room in the "Yellow House" in Arles. He wanted it to express "absolute restfulness." But look at the perspective. The floor seems to be tilting up. The furniture is slightly skewed. It feels like the room is closing in on you.

It’s a portrait of a man trying to convince himself he’s okay. He painted three versions of this. The first one was damaged in a flood, so he painted two more while he was in the asylum because he wanted to preserve the memory of that brief moment of independence. Experts like Martin Bailey, who has written extensively on Van Gogh’s time in the Yellow House, point out that the paired objects in the room—two chairs, two pillows—suggest a deep longing for a companion. He was waiting for Gauguin. He was waiting for a life that never quite materialized.

Cafe Terrace at Night: A sky without black

Van Gogh once said that "the night is more alive and more richly colored than the day." This is wild if you think about how people painted back then. Most artists used black for shadows. Vincent? He used blues, violets, and greens.

✨ Don't miss: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

In Cafe Terrace at Night, there isn't a drop of black paint in the sky. It’s all deep ultramarine. It was the first time he used those swirling stars that would later define The Starry Night. You can still visit this spot in Arles today. It’s called the Café Van Gogh. It’s a tourist trap now, obviously, but if you stand there at night and look up, you can sort of see what he saw before the neon signs and the iPhones took over.

Portraiture and the "Man with the Bandaged Ear"

Self-portraits were Vincent’s way of practicing. He couldn't afford models. He was broke, living on bread, coffee, and absinthe that his brother Theo paid for. So, he looked in the mirror.

The Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear is probably the most raw piece of "celeb" history in the art world. He’d just had a psychotic break. He’d mutilated himself. Most people would hide. Vincent? He put on his coat, grabbed a brush, and recorded the damage. He looks haunted, but also strangely calm. It’s a document of survival.

He did over 35 self-portraits. In some, he looks like a refined gentleman. In others, he looks like a ghost. He was trying on different identities, trying to find one that fit.

Wheatfield with Crows: Was it a suicide note?

For a long time, people thought Wheatfield with Crows was the last thing he ever painted. The turbulent sky, the dead-end path, the crows that look like black slashes of ink—it feels like a goodbye. It’s heavy. It’s dark.

🔗 Read more: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Actually, scholars now think Tree Roots might have been his final work. But the myth of the Wheatfield persists because we love a good tragedy. Even if it wasn't the final one, it was painted in July 1890, the month he died. He walked into those fields in Auvers-sur-Oise with a revolver.

Whether he shot himself or—as a recent, controversial biography by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith suggests—he was accidentally shot by some local teenagers, the painting remains a staggering look at a mind that was frayed at the edges. The colors are beautiful but violent.

How to actually "experience" Van Gogh today

If you want to go beyond a Google search for van gogh most famous paintings, you have to look at the letters. Over 800 of them. Mostly to Theo. They are the "user manual" for his art.

- Read the letters: Go to the Van Gogh Letters Project online. It's free. You’ll see he wasn't just a "madman." He was incredibly articulate, well-read, and spoke multiple languages.

- Look at the texture: If you can’t get to a museum, look at high-resolution scans on the Google Arts & Culture app. Zoom in until you see the cracks in the paint (craquelure).

- Visit the small spots: Skip the "Immersive Van Gogh" digital light shows if you want the real deal. Go to Auvers-sur-Oise. It’s a short train ride from Paris. You can see the church he painted, the room where he died, and his grave right next to Theo's.

Vincent didn't sell his work because it was "bad." He didn't sell it because he was 100 years ahead of his time. He was painting emotion when everyone else was still painting objects. He didn't want to show you what a flower looked like; he wanted to show you what it felt like to be alive and looking at that flower.

Stop looking at the paintings as "masterpieces." Look at them as a diary. Once you do that, the colors start to make a lot more sense. He wasn't trying to be famous. He was just trying to stay sane.

To get the most out of his work, start by tracking the evolution of his palette from the dark, earthy tones of The Potato Eaters in the Netherlands to the neon explosions of his time in Arles. You'll see a man discovering light in real-time. Use the official Van Gogh Museum database to cross-reference his letters with specific dates of his works to see exactly what he was feeling the day he put brush to canvas.

Actionable Insights for Art Enthusiasts

- Visit Chronologically: If you ever visit the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, start at the bottom and work up. Seeing his progression from "clunky" drawings to "The Starry Night" reveals his relentless work ethic.

- Study the "Japonisme" Influence: Look at his 1887 Oiran or his Almond Blossoms. He was obsessed with Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e). Understanding this explains his use of bold outlines and flat areas of color.

- Check Provenance: When looking at "Van Gogh most famous paintings" online, always verify the source. Because he's so valuable, the market is full of high-end fakes and "attributed" works that scholars still argue about.

- The "Theo" Factor: Realize that without his brother Theo, none of this exists. Theo was an art dealer who supported Vincent financially and emotionally. Their relationship is the actual backbone of the entire Post-Impressionist movement.