You probably remember sitting in a stuffy classroom, staring at that giant, colorful chart on the wall. It looked like a crossword puzzle designed by someone who loved math a little too much. Most people see the valence shell periodic table as a static map of "stuff," but honestly? It’s more like a high-stakes social network where everyone is desperate to fit in.

Everything in the universe—from the screen you're tapping on to the coffee cooling on your desk—is basically a result of atoms trying to fix their outer shells. They want to be stable. They want to be like the Noble Gases. If you understand how the valence shell works, the entire periodic table stops being a list of names and starts being a predictable guide to how the world actually sticks together.

The Outer Edge is Where the Magic Happens

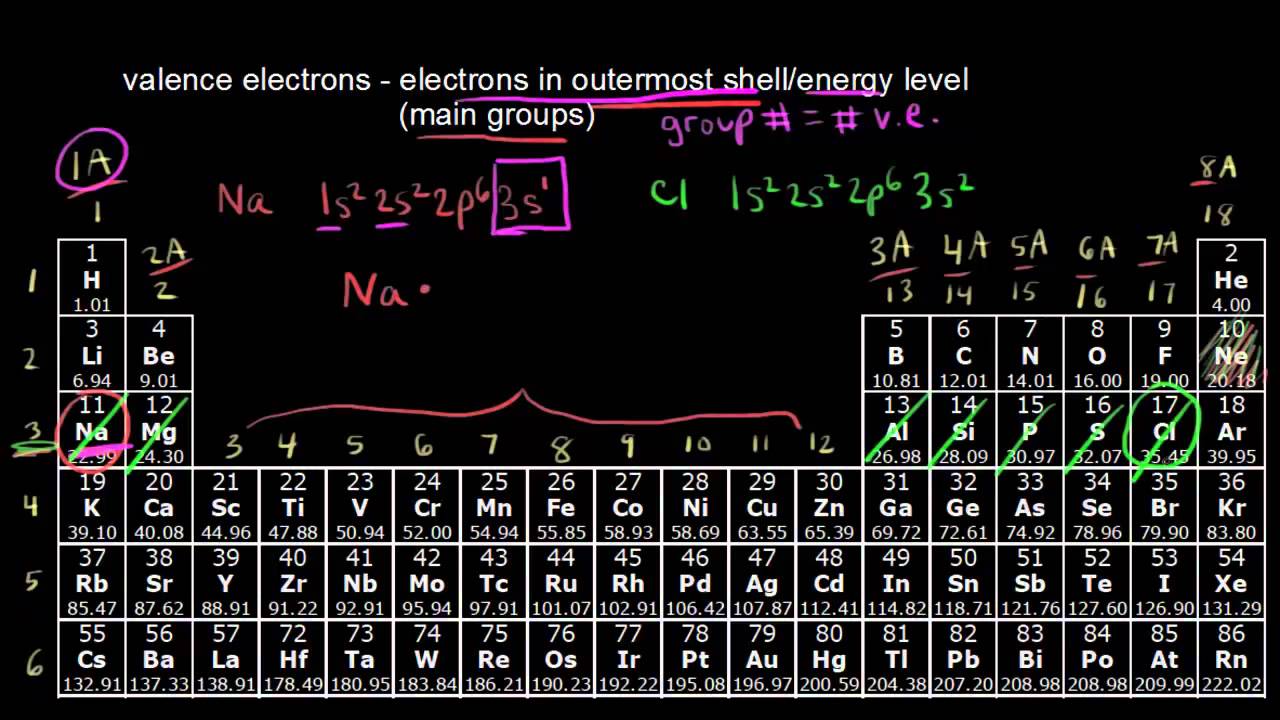

Think of an atom like an onion. Or an ogre, if you're a Shrek fan. It has layers. The inner layers are mostly "set in their ways"—they're shielded, quiet, and don't do much. But that outermost layer? That’s the valence shell. This is the only part of the atom that ever touches anything else. It's the handshake. The frontline.

When we talk about the valence shell periodic table, we're really talking about the electrons hanging out in that exterior zone. These electrons dictate if an element is a violent explosive or a boring, inert gas. For example, look at Sodium (Na). It has exactly one electron in its valence shell. It hates it. It wants that electron gone so badly that it will explode if it touches water just to get rid of it. On the flip side, Chlorine (Cl) is one electron short of a full set. It's desperate. Put them together, and they trade. You get salt. Delicious, stable, non-explosive table salt.

Why the Columns Actually Matter

If you look at the vertical columns, called groups, you’ll notice something cool. Every element in Group 1 has one valence electron. Every element in Group 17 has seven. This isn't just a neat coincidence; it’s the fundamental logic of the valence shell periodic table.

Gilbert N. Lewis, the guy who gave us those "Lewis Dot Structures" we all had to draw in high school, realized that atoms are essentially chasing a "Rule of Octet." They want eight electrons. It’s the magic number for stability. Except for Hydrogen and Helium—they're the oddballs who only want two.

The Transition Metal Mess

Now, I’ll be honest with you. The middle of the table—the Transition Metals—is a bit of a nightmare. While the "Main Group" elements (the tall towers on the left and right) follow the rules pretty well, the transition metals are like the wild west. Their d-orbitals get involved. Sometimes they use electrons from an inner shell as if they were valence electrons. This is why Iron (Fe) can be $Fe^{2+}$ or $Fe^{3+}$. It’s flexible. It’s annoying for students, but it's why our blood can carry oxygen so effectively.

Periodic Trends: More Than Just Increasing Numbers

People often think the table is just organized by weight. Not really. It’s organized by how those valence shells behave as you add more protons to the nucleus. This leads to something called Electronegativity.

Imagine a game of tug-of-war. Fluorine is the undisputed champion. It sits at the top right of the valence shell periodic table (ignoring the noble gases) and it pulls on electrons harder than anything else. As you move from left to right across a row, the atoms get "hungrier" for electrons because their valence shells are getting closer to being full.

But as you move down a column? The atoms get bigger. The valence shell is further away from the nucleus. It’s like trying to hold onto a toddler's hand while standing on the opposite side of a crowded room. The grip is weaker. This is why Francium, at the bottom left, is so incredibly reactive—it can barely hold onto its valence electron at all.

🔗 Read more: Computer Systems Servicing Module: What Most People Get Wrong About Tech Support

Real World Stakes: Semiconductors and Your Phone

We aren't just talking about abstract science here. The valence shell periodic table is the reason Silicon Valley exists. Silicon is in Group 14. It has four valence electrons. It’s right in the middle. It’s not quite a metal, not quite a non-metal. It’s a "metalloid."

Because it has four electrons, it can form these perfect, stable lattice structures. But if you "dope" it—meaning you throw in an element with five valence electrons (like Phosphorus) or three (like Boron)—you create a situation where electrons can flow. That’s a semiconductor. Your entire digital life is built on the fact that we can manipulate the valence shells of Group 14 elements.

The Misconception of "Full" Shells

One thing that drives chemists crazy is the idea that shells are like literal hard spheres. They aren't. They’re probability clouds. When we say a valence shell is "full," we mean the energy levels are balanced.

Also, don't let the "Octet Rule" fool you into thinking every atom stops at eight. Elements in Period 3 and below (like Sulfur or Phosphorus) can have "expanded octets." They have access to d-orbitals that allow them to hold 10 or 12 electrons. This is why $SF_6$ (Sulfur Hexafluoride) exists. It’s a heavy gas that makes your voice sound like Darth Vader, and it’s only possible because Sulfur's valence shell is more "spacious" than the one in Oxygen.

🔗 Read more: Chinese Phone Numbers: Why 11 Digits and "Lucky" SIMs Rule the Streets

How to Actually Use This Info

If you’re trying to predict how a chemical reaction will go, stop looking at the atomic mass. Look at the group number.

- Group 1 & 2: High reactivity, eager to lose electrons. They’re the "givers."

- Group 16 & 17: High reactivity, eager to steal electrons. They’re the "takers."

- Group 18: The Noble Gases. They are the "trust fund kids" of the periodic table. They have everything they need (a full valence shell) and they don't want to talk to anyone.

- Carbon (Group 14): The "builder." With four electrons, it can bond in four directions, which is why it’s the backbone of all life on Earth.

Subtle Nuance: Shielding and Effective Nuclear Charge

Why does the size of the atom matter? Well, it's all about the Effective Nuclear Charge ($Z_{eff}$). The inner electrons act as a screen. They block the "pull" of the positive nucleus from reaching the valence electrons.

In a large atom like Lead, those valence electrons are feeling a very muffled version of the nucleus's attraction. This makes the valence shell "loose." In a tiny atom like Oxygen, there’s very little shielding. The nucleus is practically screaming at the valence electrons to stay put. This tension—the battle between the pull of the center and the distance of the edge—is what creates every chemical bond in existence.

Moving Beyond the Basics

To truly master the valence shell periodic table, you have to stop seeing it as a chart and start seeing it as a set of energy states. Electrons don't like being crowded, but they love being close to the nucleus. It’s a balancing act.

If you're a student or just a curious nerd, the best thing you can do is memorize the "S, P, D, F" blocks.

- S-block: Groups 1 and 2.

- P-block: Groups 13 through 18.

- D-block: The transition metals.

- F-block: The weird rows at the bottom (Lanthanides and Actinides).

Once you see the blocks, you see the electron configurations. Once you see the configurations, you see the valence shell. And once you see the valence shell, you see how the entire physical world is put together.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Steps

- Visualize the 'Gaps': Next time you look at the table, don't look at the letters. Look at how many spaces are left until the end of the row. That's the "hunger" level of the atom.

- Check the Oxidation States: If you're looking at a supplement bottle or a cleaning product, look up the elements. If you see something from Group 1 (like Potassium), you know it’s likely there as an ion because it easily lost its one valence electron.

- Dopant Awareness: If you’re interested in tech, look into how Gallium (3 valence electrons) and Arsenic (5 valence electrons) are used together to make high-speed LEDs. It’s all a game of balancing that outer shell.

- Practice Lewis Diagrams: If you want to understand bonding, draw the dots. It seems childish, but it's the fastest way to see why Carbon Dioxide ($CO_2$) forms double bonds while Methane ($CH_4$) forms single ones.

The valence shell periodic table isn't just a classroom decoration. It's the blueprint for the universe's construction site. Whether you're trying to pass a test or just trying to understand why your phone battery works the way it does, the answer is always hidden in that thin, outermost layer of the atom.