If you look through a microscope at a slice of an onion and then at a cheek swab, the first thing that hits you isn't the nucleus. It’s the empty space. Or, what looks like empty space. In reality, those "bubbles" are vacuoles, and they are basically the storage lockers of the cellular world. But here's the kicker: how vacuoles are different in plant and animal cells is one of the most fundamental distinctions in biology. It isn't just a minor tweak in design. It’s a total shift in survival strategy.

Most people think of vacuoles as just "storage." Boring, right? Wrong. In a plant, that vacuole is a hydraulic press. In an animal, it’s more like a wandering garbage truck or a temporary pantry. They share a name, but their day-to-day jobs couldn't be more different.

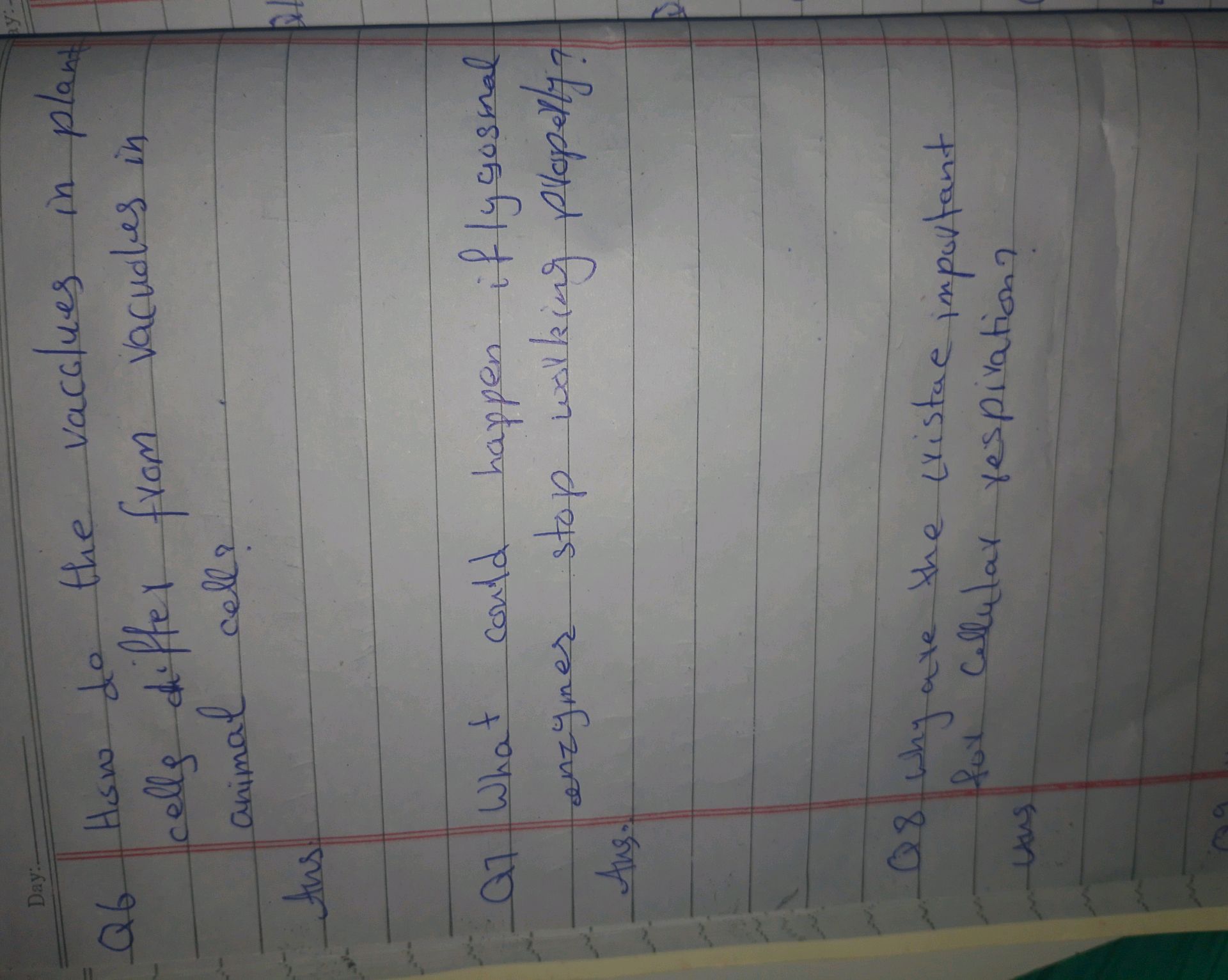

The Giant in the Room: The Central Vacuole

In a mature plant cell, the vacuole is the protagonist. It’s huge. We are talking up to 90% of the total cell volume in some species. Biologists call this the Central Vacuole. Imagine moving into a studio apartment where the closet takes up almost the entire room, pushing your bed and kitchen against the walls. That’s exactly what happens to the nucleus and chloroplasts; they get shoved to the periphery by this massive, fluid-filled sac.

Why so big? Plants don't have skeletons. They can't run to a shady spot when they're thirsty. They rely on turgor pressure.

Basically, the vacuole pumps itself full of water and solutes, pushing outward against the rigid cell wall. This internal pressure is what keeps a sunflower standing tall instead of flopping over like a wet noodle. When you forget to water your houseplants and they wilt, you're literally watching millions of central vacuoles deflating. The pressure drops, the walls lose their support, and the whole structure collapses.

What’s inside that liquid?

It’s not just water. It’s a complex "cell sap." This cocktail includes sugars, proteins, and mineral salts. In many flowers, the vacuoles also store anthocyanins—the pigments responsible for those brilliant reds, purples, and blues.

✨ Don't miss: The Portable Monitor Extender for Laptop: Why Most People Choose the Wrong One

There's a darker side, too. Because plants can’t run away from herbivores, many species store bitter tannins or even toxic alkaloids inside their vacuoles. One bite from a caterpillar, and the vacuole ruptures, releasing a chemical "keep out" sign that tastes like garbage or kills the pest outright. It’s a storage locker that doubles as a chemical weapons silo.

The Nomadic Lifestyle of Animal Vacuoles

Animal cells take a totally different approach. You won't find a single, massive central vacuole here. Instead, animal vacuoles are small, numerous, and often temporary. They’re the "gig workers" of the cell.

In humans and other animals, these organelles are mostly involved in exocytosis and endocytosis. They move stuff. If a cell needs to eat (phagocytosis), it wraps its membrane around a food particle, creates a temporary food vacuole, and then fuses it with a lysosome to digest the contents. Once the job is done, the vacuole often disappears.

They’re tiny. Really tiny. Compared to the massive "lake" in a plant cell, animal vacuoles are more like puddles.

Breaking Down the Structural Differences

Let's get into the nitty-gritty of how vacuoles are different in plant and animal cells when it comes to their actual physical makeup.

🔗 Read more: Silicon Valley on US Map: Where the Tech Magic Actually Happens

The plant vacuole is encased in a specialized membrane called the tonoplast. This isn't just a simple wrapper. The tonoplast is highly active, loaded with protein pumps that move protons ($H^+$) into the vacuole to keep it acidic. This acidity is crucial for breaking down waste, much like the stomach-like function of a lysosome in animal cells.

Animal cells actually have lysosomes for that heavy-duty digestion. In plants, the central vacuole often takes over that role because it has the space and the acidic environment to handle it. This is a nuance many textbooks gloss over: the plant vacuole is a multi-tool. It's a skeleton, a stomach, and a pantry all in one.

In animals, vacuoles are often classified by their specific job:

- Contractile Vacuoles: Found in many freshwater protists like Amoeba or Paramecium. These are basically little pumps that squirt excess water out of the cell so it doesn't explode.

- Food Vacuoles: Temporary sacs containing nutrients waiting to be broken down.

- Secretory Vacuoles: Little bubbles carrying hormones or neurotransmitters to the cell surface to be released into the body.

Survival Tactics and Environmental Stress

The way these vacuoles function tells a story about evolution. Plants are stationary. They deal with feast or famine in terms of rainfall. The large central vacuole allows them to grow very large very quickly without needing to manufacture tons of expensive cytoplasm. They just fill the "balloon" with cheap water. This is how a weed can grow three inches in a day. It’s mostly water-weight held under high pressure.

Animals, being mobile, can’t afford to be heavy balloons filled with water. We need to be dense, muscular, and agile. Having a giant, water-filled sac in our cells would make us incredibly fragile and inefficient. Our vacuoles are optimized for transport and rapid recycling of materials, not for structural support.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Best Wallpaper 4k for PC Without Getting Scammed

Is it ever the other way around?

Biology loves to break its own rules. While the "one large plant vacuole vs. many small animal vacuoles" rule holds 99% of the time, there are weird outliers. Some immature plant cells start with several small vacuoles that eventually fuse into one as the cell grows. Some specialized animal cells might have larger-than-average vacuoles for specific storage needs, like in certain fat-storing cells, though even then, they don't function like the turgor-providing plant version.

Key Takeaways for Students and Hobbyists

When you're trying to remember how vacuoles are different in plant and animal cells, honestly, just think about a house versus a car.

A plant cell is like a house. It needs a massive water tank (the central vacuole) to keep the plumbing working and the structure stable. It stays in one place.

An animal cell is like a car. It’s smaller, it moves, and it uses small, specialized containers (small vacuoles) to hold onto snacks for the road or to carry trash to the curb.

Actionable Insights for Biology Success:

- Look for the Tonoplast: If you're identifying a cell under a high-res micrograph, look for the tonoplast membrane. If it’s there, you’re almost certainly looking at a plant.

- Check the Position of the Nucleus: In animal cells, the nucleus is usually central. In plants, it’s often squished against the side. If you see a nucleus that looks like it's being bullied by a giant empty bubble, that bubble is a central vacuole.

- Turgor Test: Remember that wilting is a vacuole issue, not a "cell death" issue initially. Adding water can often "re-inflate" the plant because the vacuoles are still functional; they're just empty.

- Waste Management: Remember that animal cells rely more on lysosomes for waste, while plant cells use their central vacuole as a secondary waste site.

Understanding these differences isn't just about passing a quiz. It’s about understanding why a tree can grow 300 feet tall without a skeleton and why humans can move with such fluidity. It all comes back to how these tiny (or not-so-tiny) bubbles manage their space.