You probably remember that one biology diagram from middle school. It showed a big, blue blob in the middle of a plant cell, labeled "vacuole." It looked like a giant swimming pool taking up all the space. If you're studying for an exam or just fell down a Wikipedia rabbit hole, you're likely asking: is a vacuole prokaryotic or eukaryotic?

The short answer? Vacuoles are a hallmark of eukaryotic cells.

But science is rarely that clean. If you tell a microbiologist that prokaryotes never have vacuole-like structures, they might actually roll their eyes at you. Biology is messy. It’s full of "well, actually" moments. While eukaryotes—like plants, animals, and fungi—rely on these membrane-bound sacs for survival, some bacteria have found ways to mimic them.

The Eukaryotic Powerhouse: More Than Just a Bag of Water

In the world of eukaryotes, the vacuole is the MVP of storage. In plant cells, it’s often the largest organelle. It isn't just sitting there. It creates turgor pressure. This is basically the internal water pressure that keeps a plant from wilting. When you forget to water your peace lily and it droops? That’s because the vacuoles are shrinking.

Animal cells have them too, but they're tiny and temporary. They act like little "delivery trucks" or "trash bins," moving nutrients in or breaking down waste. Protists, which are single-celled eukaryotes like Amoeba or Paramecium, use specialized "contractile vacuoles" to pump out excess water so they don't literally explode in freshwater environments.

What’s Inside the Sac?

It’s not just water. Depending on the cell, a vacuole might contain:

- Enzymes for breaking down molecules.

- Waste products that would be toxic if they floated around the cytoplasm.

- Pigments (like the ones that make flower petals red or purple).

- Stored nutrients like proteins in seeds.

The Prokaryotic Twist: Do Bacteria Have Vacuoles?

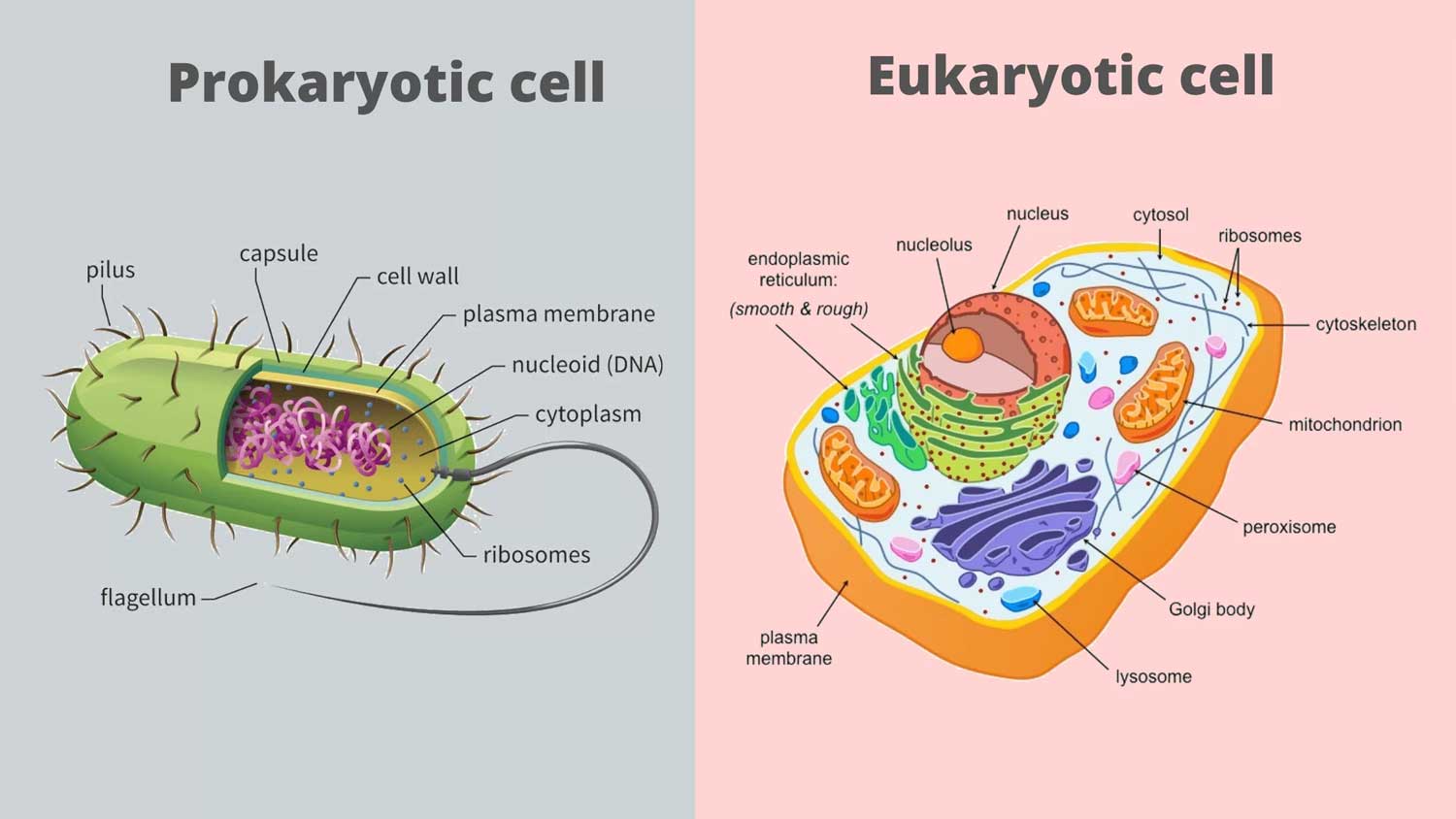

Technically, no. By definition, a vacuole is a membrane-bound organelle. Prokaryotes—bacteria and archaea—are famous for not having membrane-bound organelles. They like to keep things simple. Their DNA just floats around in the nucleoid, and they don't have a Golgi apparatus or endoplasmic reticulum.

However, nature loves to break its own rules.

Enter "gas vacuoles." You’ll find these in cyanobacteria and some soil bacteria. These aren't actually vacuoles in the eukaryotic sense. They are clusters of small, protein-shelled cylinders called gas vesicles. They allow the bacteria to float or sink in the water column to find the perfect amount of sunlight or oxygen.

👉 See also: Why Translate English to Japanese Is Harder Than You Think

Then there is Thiomargarita namibiensis. This is a literal giant in the bacterial world. It's visible to the naked eye. How does it get so big? It has a massive central "vacuole" (technically a storage nitrate vacuole) that takes up about 98% of its volume. While it serves the same purpose as a eukaryotic vacuole, its structural origin is different. This is a rare exception that proves the rule.

Comparing the Two: Vacuole Prokaryotic or Eukaryotic Structures

When we look at the vacuole prokaryotic or eukaryotic debate, we have to look at the "skin" of the organelle.

Eukaryotic vacuoles are wrapped in a phospholipid bilayer called the tonoplast. This membrane is sophisticated. It has protein pumps that move ions in and out, maintaining the pH of the cell. It’s a dynamic, living border.

Prokaryotic "vacuoles" (gas vesicles) are usually just protein shells. They aren't "alive" in the same way. They don't merge with other membranes. They are rigid structures designed for buoyancy, not complex metabolism.

Why Does It Matter?

It comes down to efficiency. Eukaryotes are much larger than prokaryotes. As a cell gets bigger, its volume increases faster than its surface area.

✨ Don't miss: Windows 11 S Mode Explained: What Most People Get Wrong

If you're a giant plant cell, you can't just wait for nutrients to drift in from the outside. You need internal compartments to manage the distance. The vacuole solves this by pushing the "active" parts of the cell (the cytoplasm) against the outer wall, making it easier for the cell to exchange gases and nutrients with its environment. Prokaryotes stay small, so they generally don't need that extra help.

Misconceptions That Mess People Up

Many students get confused because textbooks simplify things too much. You might hear that "animal cells don't have vacuoles." That's wrong. They do. They're just small and often called vesicles.

Another big one? The idea that vacuoles are "dead space." Absolutely not. They are chemically active. In some fungi, the vacuole acts like a lysosome, filled with acidic enzymes that chew up old cell parts. It's more like a recycling center than a storage locker.

The Evolutionary "Why"

Why did eukaryotes evolve these and prokaryotes (mostly) didn't? It's about the "Luxury of Complexity."

Eukaryotes have a lot of energy to burn thanks to mitochondria. This energy allows them to build and maintain complex internal membranes. Prokaryotes are the "minimalists" of the biological world. They travel light. Building a membrane-bound organelle takes a lot of ATP (energy). For a bacterium, it's often more efficient to just be small and fast.

Real-World Applications

Understanding these structures isn't just for passing biology 101.

📖 Related: Stellar Acoustics: Why the Sound of Stars is Actually Science, Not Science Fiction

- Agriculture: Scientists study plant vacuoles to create crops that can survive droughts by holding onto water more effectively.

- Medicine: Some fungal infections are treated by targeting the vacuole’s ability to regulate pH. If you break the vacuole, you kill the fungus.

- Biotech: Gas vesicles from bacteria are being researched as "contrast agents" for ultrasound imaging because they reflect sound waves differently than human tissue.

How to Identify Them in the Lab

If you’re looking under a microscope, identifying a vacuole prokaryotic or eukaryotic is usually about scale.

In a plant cell, use a stain like Neutral Red. The vacuole will soak it up, turning a vibrant color while the rest of the cell stays relatively clear. In bacteria, you’re unlikely to see anything resembling a vacuole unless you’re using an electron microscope to look at those specific gas-forming species.

Practical Next Steps for Students and Researchers

If you are trying to master this topic for a course or a project, don't just memorize the "yes/no" answer.

- Map the differences: Draw a plant cell and a Thiomargarita side-by-side. Note that while both have a "big empty space," the plant's version is made of lipids and the bacterium's version is essentially a nitrate storage tank.

- Check the species: If you're looking at an organism and it has a nucleus, it's eukaryotic, and that sac is a true vacuole. No nucleus? It's a prokaryote, and that "bubble" is likely a gas vesicle or a storage granule.

- Read the latest on Thiomargarita magnifica: This species, discovered relatively recently, continues to challenge our ideas of how big and complex a prokaryote can actually be.

The distinction between vacuole prokaryotic or eukaryotic is a perfect example of why biology is fascinating. It starts with a simple rule—prokaryotes don't have organelles—and then introduces you to the weird, wonderful exceptions that make life work in extreme environments.

Focus on the membrane. If it’s a membrane-bound sac used for storage or pressure, it’s a eukaryotic vacuole. If it’s a protein-coated bubble for floating, it’s a prokaryotic specialized structure. Keep that distinction clear, and you'll never get tripped up by a "trick" question again.