You probably remember that distinct, slightly metallic smell of a high school biology lab. Dust in the air, the hum of an overhead fan, and those heavy, black or beige metal boxes sitting on the counters. Most people treat using a compound light microscope like they’re trying to crack a safe—lots of frantic knob-turning and squinting until something, anything, looks sharp. But honestly? Most of us were taught the wrong way. We were taught to "find the bug" rather than manage the light.

If you can’t see the nucleus of a cheek cell, it’s usually not because the microscope is "bad." It’s because you’re likely blasting the specimen with way too much light or skipping the most important part of the optical path: the condenser. Modern microscopy isn't just about magnification. It’s about contrast. Without contrast, a clear cell is just an invisible blob in a sea of white light.

The Anatomy of a Compound Light Microscope (And What You Can Ignore)

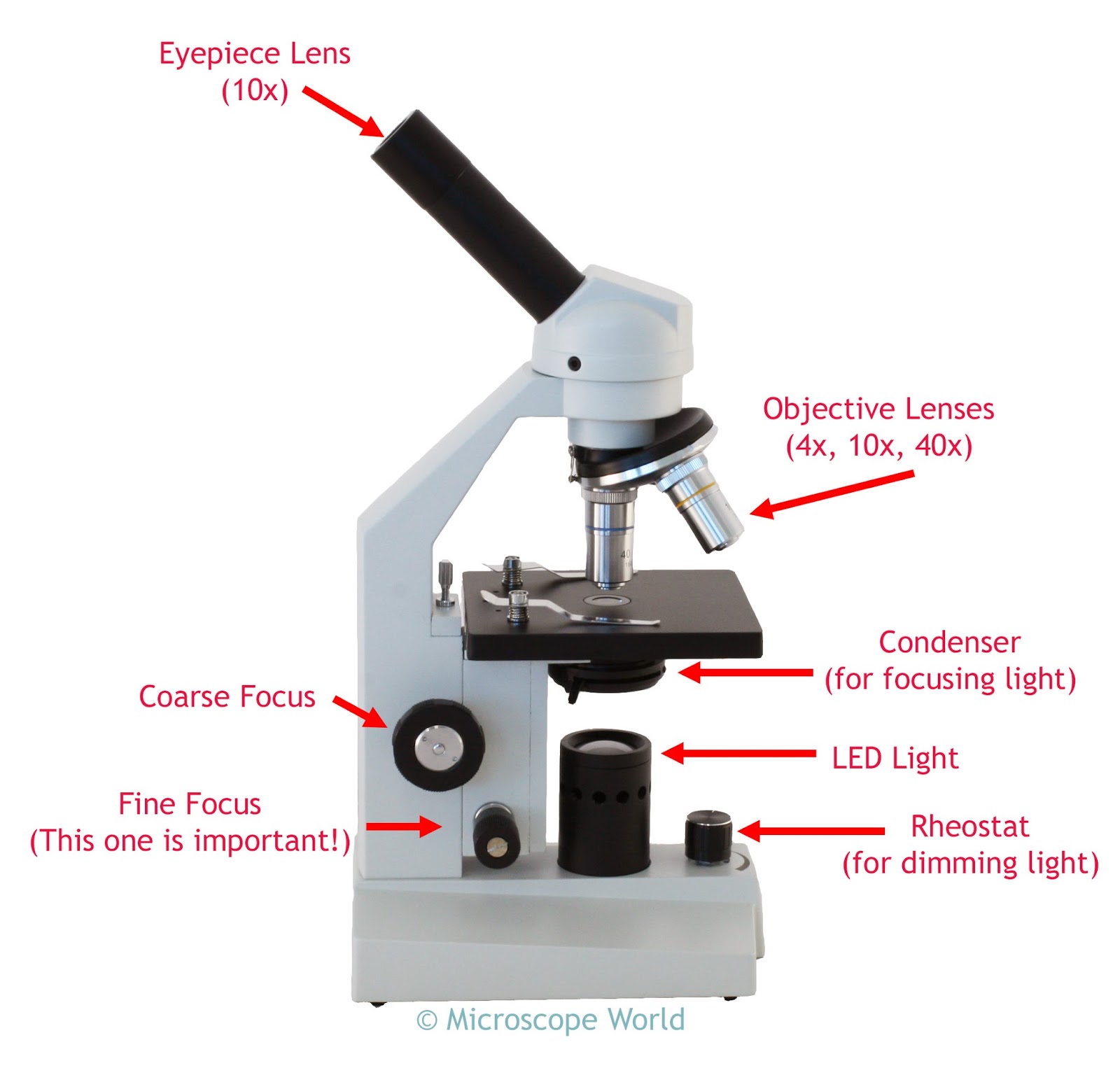

A compound light microscope uses two sets of lenses to multiply magnification. It’s basically a relay race for photons. The objective lens gathers light from the specimen, and the ocular lens—the part your eye actually touches—magnifies that image again. Most standard lab models, like those from Leica or Nikon, cap out at 1000x or 1500x total magnification. Anything beyond that is "empty magnification," where the image gets bigger but not clearer.

Focus on the mechanical stage. If your microscope has one, those two knobs hanging down are your best friends. They allow for x-y axis movement. Older models require you to push the glass slide around with your fingers, which is a nightmare when you're at 400x and a millimeter of movement feels like a mile.

The real MVP, however, is the iris diaphragm. Located right under the stage, this little lever controls the diameter of the light beam. Think of it like the pupil of your eye. When you're at low power, you need less light. As you click into higher magnification, you need to open that iris up. Most beginners leave it wide open all the time, which "washes out" the specimen. It’s like trying to see a white cat in a snowstorm.

How to Use a Compound Light Microscope Without Breaking the Glass

Safety first sounds cliché, but when a 40x objective lens smashes into a $50 prepared slide, the "crunch" is heart-wrenching. It’s a rite of passage, but one you can avoid.

👉 See also: Hard Math Equations Algebra: Why They Still Break Brains and How to Solve Them

- Start at the bottom. Always. The 4x objective (usually the shortest one with a red ring) is your "scouting" lens. It has the widest field of view.

- The coarse adjustment is for 4x only. This is the big knob. Once you move past the 4x or 10x lenses, you should almost never touch the coarse adjustment again. If you do, you risk driving the lens right through your sample.

- Center the specimen. Before you even think about zooming in, make sure the "thing" you want to see is dead-center in your field of view. As you increase magnification, the area you see gets smaller. If it’s not centered at 4x, it’ll be gone at 40x.

When you rotate to the 10x (yellow) or 40x (blue) lenses, only use the fine adjustment knob. This moves the stage in microscopic increments. At these levels, the depth of field is incredibly shallow. You might see the top of a cell but not the bottom. You have to "dance" with the fine focus, rolling it back and forth to see different layers of the specimen. It’s a 3D object, even if it looks 2D.

The Mystery of the 100x Oil Immersion Lens

Eventually, you'll see the lens with the white ring. The 100x. This is where things get messy—literally. You cannot use this lens dry. Light bends (refracts) when it moves from glass to air and back into glass. At such high magnification, that bending causes the light to scatter, making the image a fuzzy mess.

[Image showing the path of light through air versus immersion oil between a microscope slide and an objective lens]

You have to bridge that gap with a tiny drop of specialized cedarwood or synthetic immersion oil. The oil has the same refractive index as glass. Basically, the light "thinks" it's still traveling through glass, so it doesn't bend. It goes straight into the lens.

Pro tip: If you get oil on the 40x lens by accident, clean it immediately with lens paper. Not Kimwipes. Not your shirt. Lens paper. The 40x lens is not sealed, and oil can seep inside, ruining the internal optics forever. It’s an expensive mistake.

👉 See also: Reverse lookup with phone number: What most people get wrong about finding the caller

Why Contrast Matters More Than Power

If you're looking at live protists from a pond, they are mostly water. They are transparent. This is why using a compound light microscope effectively often requires staining. Methylene blue or iodine are the classics. They bind to DNA or starch, making the internal structures pop.

But what if you don't want to kill the specimen with chemicals?

This is where you play with the sub-stage condenser. By lowering the condenser slightly or closing the diaphragm more than "recommended," you create shadows around the edges of transparent objects. This is a "poor man's phase contrast." It creates enough artificial shadow to see the cilia beating on a paramecium or the movement of a nucleus without needing to dye it.

Common Troubleshooting (What to do when it's all black)

- Is the light on? Seriously. Check the plug.

- Is the objective clicked in? If the lens isn't fully snapped into the nosepiece, the light path is blocked.

- Is the diaphragm closed? If you've got it shut tight, no light gets through.

- Is the slide upside down? This happens more than people admit. If the cover slip is on the bottom, the high-power lenses won't be able to get close enough to focus.

Real-World Applications: More Than Just School Labs

Beyond the classroom, these tools are workhorses. In 2024, clinical pathologists still rely on light microscopy to catch malaria parasites in blood smears or identify cancerous cells in a biopsy. Hematology labs use specialized counting chambers called hemocytometers under a light microscope to manually check blood cell counts when automated machines give an error.

Even in the age of electron microscopes that can see atoms, the compound light microscope is king for one reason: it can look at things while they are still alive. You can't put a living cell in a vacuum-sealed, gold-coated electron microscope chamber. If you want to see a cell divide in real-time, you use light.

📖 Related: How to find passwords for apps on iPhone: Why checking Settings isn't enough anymore

Taking Care of the Optics

Dust is the enemy. Always cover your scope when you're done. When you carry it, use two hands—one on the "arm" and one under the "base." These things are surprisingly heavy because of the lead-glass lenses and cast-iron frames.

If your view has "specks" that stay in the same place when you move the slide, the dirt is on your lenses. Rotate the eyepiece. If the dirt rotates too, it’s on the eyepiece. If not, check the objective. Use a specialized cleaning solution and move in a circular motion. Scratches are permanent, so be gentle.

Moving Forward With Your Observations

Ready to actually see something cool? Don't just look at the pre-made slides of "onion skin." Go find some standing water from a flower vase or a birdbath. Use a pipette to grab a drop from the very bottom where the "gunk" settles.

- Place the drop on a clean slide.

- Drop a cover slip on at a 45-degree angle to avoid air bubbles.

- Start at 4x magnification with the diaphragm nearly closed.

- Slowly increase the light as you move up to 10x and 40x.

You'll see a hidden world of rotifers, tardigrades, and diatoms. It's a chaotic, busy universe happening in a single drop of water. Once you master the balance of light and focus, the microscope stops being a piece of lab equipment and starts being a portal. Keep your eyes open, keep the diaphragm adjusted, and never force a knob if it feels stuck.