If you’ve ever looked at a US national debt over time graph, you probably felt a little bit of vertigo. It’s not just a line going up; it’s a line that looks like it’s trying to escape the top of the chart. Honestly, it’s kind of terrifying when you first see it. We just hit $38.4 trillion in early 2026, and the speed at which we’re adding to that total is, frankly, wild.

But here’s the thing: most people read these graphs all wrong. They look at the raw dollar amount and freak out. While $38 trillion is a massive, almost incomprehensible number, it doesn’t tell the whole story of whether the country is actually "broke" or just heavily leveraged. To understand the real situation, you have to look past the scary curve and see what’s actually driving those spikes.

Why the Raw Dollars on a US National Debt Over Time Graph Lie to You

If you look at a graph of the debt in pure dollars starting from 1790, it looks like nothing happened for 200 years, and then suddenly the world ended in the year 2000. That’s because $1 billion in 1865 (the end of the Civil War) was an astronomical amount of money, but on a chart next to $38 trillion, it looks like a flat line at zero.

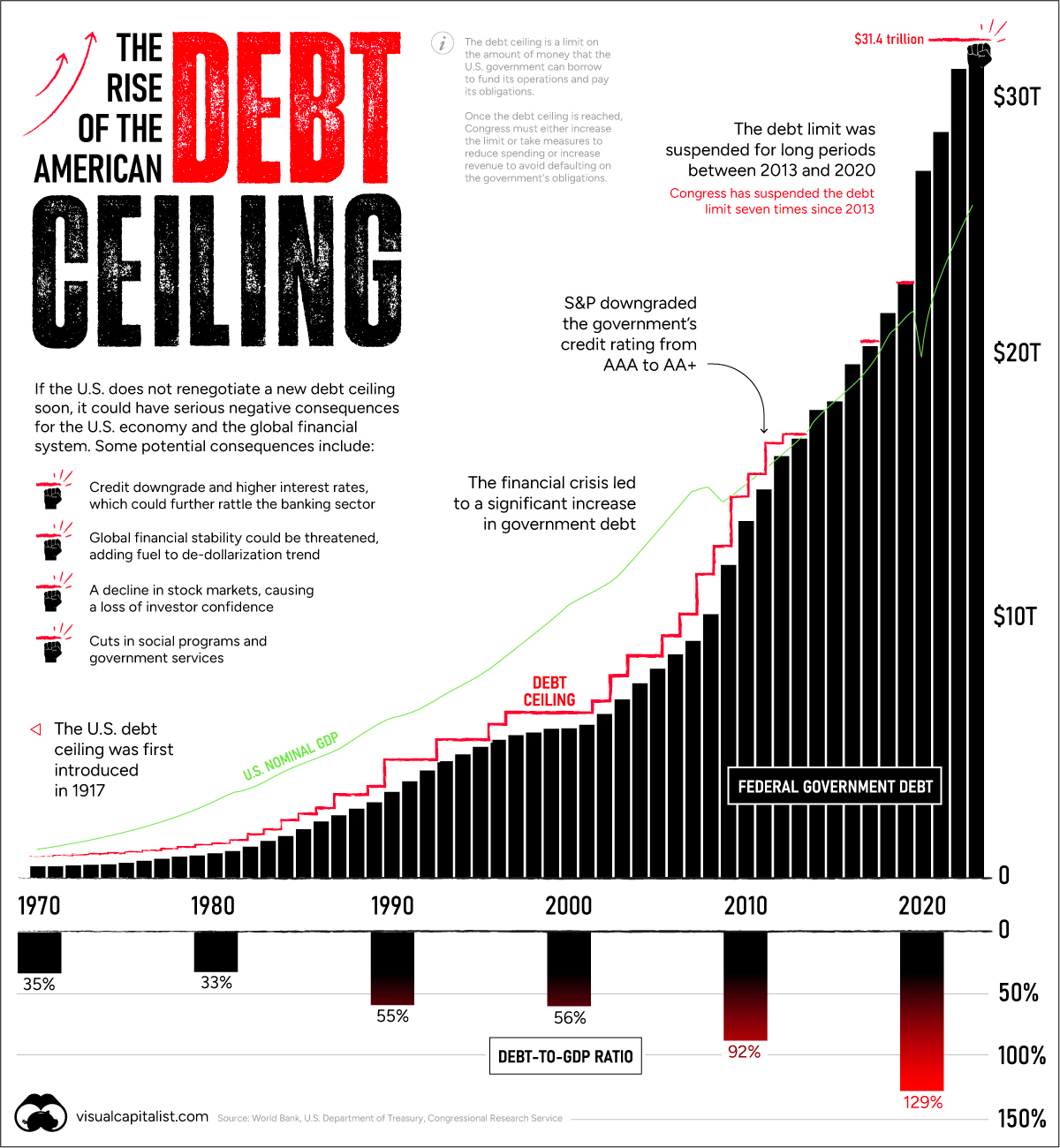

To get a real sense of the "weight" of the debt, experts like those at the U.S. Treasury and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) prefer looking at the Debt-to-GDP ratio. This basically compares what we owe to what we produce. Think of it like a mortgage: a $500,000 debt is ruinous for someone making $30,000 a year, but it’s pocket change for a billionaire.

👉 See also: Stock Market Real Time: Why Your Screen Is Lying To You (Sorta)

Right now, our debt-to-GDP ratio is sitting around 124%. For context, we actually broke the previous World War II record of 118% back in 2020 during the pandemic. We’ve been living in "uncharted territory" for a few years now, and the graph shows no sign of heading back down to the 30% or 40% levels that were normal in the 1960s and 70s.

The Big Spikes: What Actually Pushes the Line Up?

The US national debt over time graph isn't a smooth ramp. It’s a series of jumps. If you trace the line back, you can see the "scars" of American history written in the data.

- The Revolutionary War: We started with about $75 million in debt. Alexander Hamilton basically argued that a bit of debt was good—it "cemented" the union because people wanted the government to survive so they’d get paid back.

- The Civil War: Debt jumped 4,000%. We went from $65 million to $2.7 billion in just a few years.

- World War II: This was the "Big One." The ratio hit 118%. But after the war, we actually managed to bring that ratio down significantly—not by paying off the debt, but by growing the economy so fast that the debt became "small" by comparison.

- The 21st Century "Hockey Stick": This is where the graph goes vertical. Between the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve added more debt in 20 years than in the previous 200.

Basically, we used to borrow for emergencies (wars and depressions) and then "grow" our way out of it during peace time. Now, we’re borrowing even when the economy is technically doing okay. That’s a huge shift in how the US handles its checkbook.

The Hidden Driver: Interest Rates

Something most people ignore when looking at a US national debt over time graph is the cost of "carrying" that debt. For a long time, interest rates were near zero. It was basically free money. But as of late 2025 and early 2026, the average interest rate on our debt has climbed to over 3.3%.

That might sound low, but when you owe $38 trillion, a 3% interest bill is more than $1 trillion a year. In 2024, for the first time, we spent more on interest than we did on the entire National Defense budget. That is a massive milestone that most people completely missed. We are now paying more for the "privilege" of our past spending than we are to protect the country today.

Is This Sustainable? (What the Experts Say)

There’s a lot of debate here, and honestly, nobody has a crystal ball. On one side, you have folks who point out that the US prints its own currency. We can’t "run out" of dollars. As long as the world wants to buy Treasury bonds—which they still do, because the US is seen as the safest bet in a messy world—we can keep this going.

But there’s a limit. Economists like Alan Auerbach at Brookings have pointed out that we are on an "unsustainable path." If the debt-to-GDP ratio keeps climbing toward 200% or 300% over the next few decades, it could "crowd out" private investment. Basically, if the government is sucking up all the available cash to pay its bills, there’s less money for businesses to grow, which slows down the whole economy.

Another weird factor in 2026 is the role of tariffs. Recent policy shifts have increased customs duties significantly. While the CBO suggests this might bring in a few trillion over the next decade to help reduce the deficit, it also risks making our trading partners (like Japan and the EU) less likely to buy our debt. If they stop buying, interest rates go even higher. It’s a delicate, sorta scary balancing act.

Breaking Down the $38 Trillion

Who do we actually owe all this money to? A lot of people think it’s all "China," but that’s a myth.

- The Public: This is the biggest chunk. It includes regular people with savings bonds, pension funds, and big banks.

- Foreign Governments: Japan is actually the largest foreign holder now, followed by China. But together, foreign countries only hold about 25-30% of the total.

- The Government itself: This sounds crazy, but the government owes itself money. Specifically, the Social Security Trust Fund "lends" its extra cash to the Treasury.

Actionable Insights: How This Affects Your Wallet

You might think "that’s a Washington problem," but the US national debt over time graph eventually hits your bank account. Here is how you should think about it as we move through 2026:

- Inflation Risk: When the government borrows and spends this much, it can devalue the dollar. Keeping some of your savings in "hard" assets or inflation-protected securities (like TIPS) isn't a bad idea.

- Tax Volatility: At some point, the "math" has to work. Most experts agree that we can't just cut spending to fix this; we’ll likely see tax increases eventually. If you have the option to lock in current tax rates (like with a Roth IRA), it might be worth considering.

- Interest Rates: High national debt usually keeps upward pressure on interest rates. Don't expect the era of 3% mortgages to come back anytime soon. The government is competing with you for loans, and they have deeper pockets.

The best thing you can do is stay informed. Watch the Debt-to-GDP ratio more than the total dollar amount. If that ratio starts to stabilize, we might be okay. If it keeps skyrocketing even during "good" economic years, then it’s time to get a bit more defensive with your personal finances.

To keep a closer eye on these numbers as they change, you can track the daily updates at FiscalData.Treasury.gov or use the CBO’s Budget and Economic Outlook reports which come out a few times a year. These are the gold standards for seeing where that line on the graph is headed next.