The numbers are honestly getting hard to wrap your head around. When you look at a US national debt historical chart, it doesn’t even look like a normal graph anymore. It looks like a rocket ship. We’re sitting at over $34 trillion—heading fast toward $35 trillion—and if you’re like most people, you probably wonder when the "bill" actually comes due. Or if it ever does.

Money is weird.

For decades, the debt was a relatively flat line. Sure, it went up, but it stayed in a range that seemed manageable compared to the size of the entire US economy. Then, the 2000s happened. Then 2008 happened. Then a global pandemic happened. Every time the world hit a snag, the chart didn't just tick up; it leaped. It’s not just about "spending too much." It’s a complex mix of tax cuts, wars, social safety nets, and a global financial system that basically relies on the US dollar being the safest bet in the room.

The Long View of the US National Debt Historical Chart

If you zoom all the way out to the beginning of the country, the story is actually pretty fascinating. Alexander Hamilton, the first Treasury Secretary, famously called a national debt a "national blessing" if it wasn't excessive. He thought it tied the interests of the wealthy to the success of the government.

For over a century, the chart followed a very predictable "mountain" pattern. We’d borrow huge amounts of money to fight a war, like the Civil War or World War I, and then we’d spend the next twenty years paying it down. The goal was always to get back to zero, or at least close to it.

Everything changed after World War II.

In 1946, the debt-to-GDP ratio hit 106%. That was the record for a long time. But instead of just paying it off, the economy grew so fast in the 1950s and 60s that the debt effectively "shrank" relative to how much money the country was making. It’s like having a $10,000 credit card balance when you make $30,000 a year versus having that same balance when you make $200,000. The debt didn't vanish, but it mattered less.

The 1980s Inflection Point

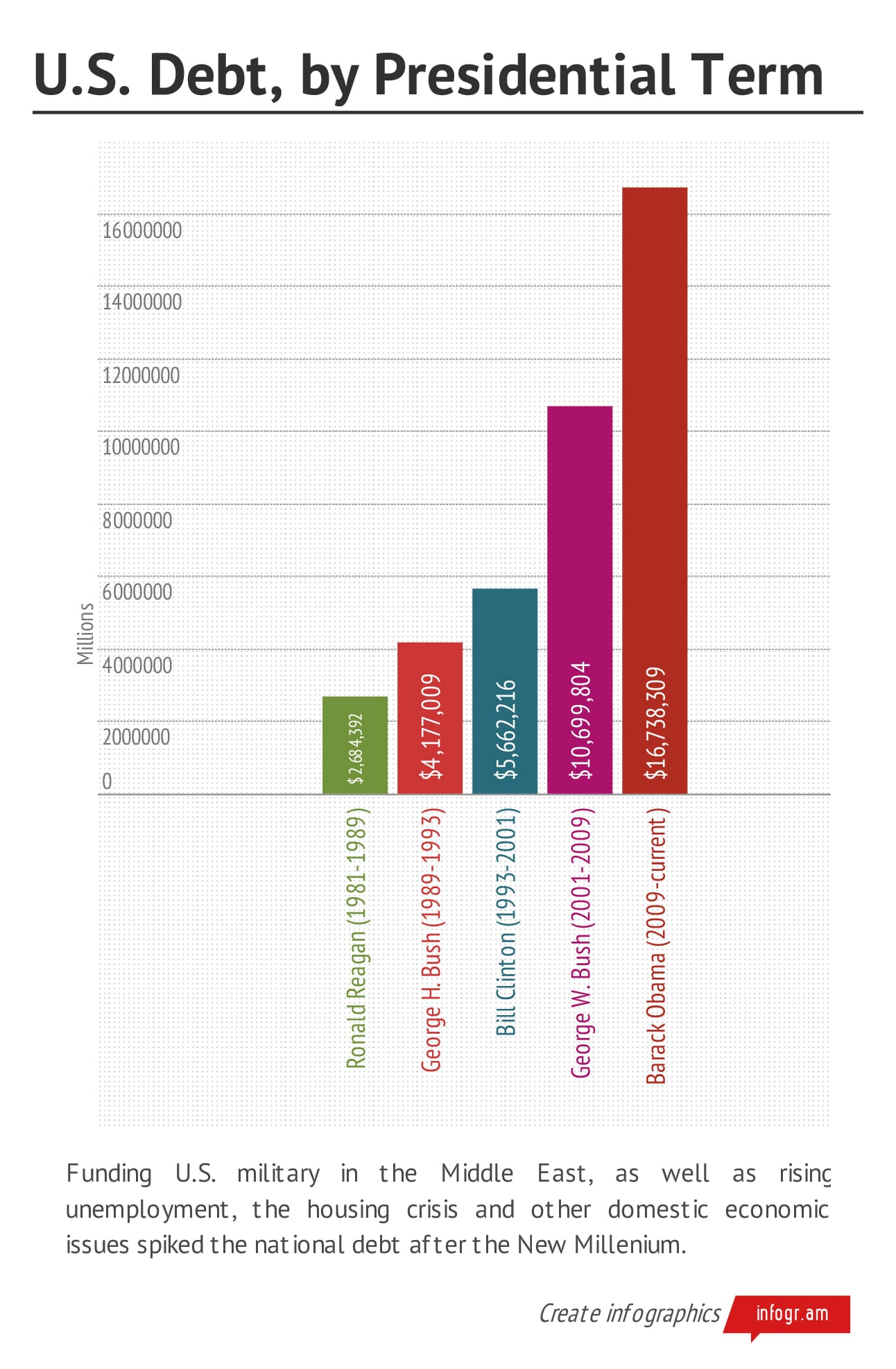

The real "upward turn" on the modern US national debt historical chart starts in the early 1980s. This is where the old rules about paying off war debt seemed to go out the window. Under the Reagan administration, the US combined massive increases in defense spending with significant tax cuts. The idea was "Supply-Side Economics"—the belief that lower taxes would spark so much growth that the debt wouldn't matter.

📖 Related: Private Credit News Today: Why the Golden Age is Getting a Reality Check

It didn't quite work out that way. The debt tripled in a decade.

By the time Bill Clinton took office, there was a genuine panic about the deficit. For a brief, shining moment in the late 1990s, the US actually ran a surplus. People were literally talking about what would happen if the national debt disappeared entirely. Imagine that. But then came the 2001 recession, the 9/11 attacks, and two very expensive wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The surplus evaporated, and the chart started its vertical climb.

Why the Chart Looks Like a Hockey Stick Now

If you look at a chart from 2008 to 2024, the angle is staggering. There are two main culprits: the Great Recession and COVID-19.

When the housing market collapsed in 2008, the government stepped in with the TARP program and various stimulus packages to keep the global economy from flatlining. Tax revenue plummeted because people weren't working. Spending went up because people needed help. Then, just as things were starting to stabilize, 2020 arrived.

The response to the pandemic was a fiscal explosion. We’re talking trillions of dollars in CARES Act funding, PPP loans, and direct checks to households.

The Interest Rate Trap

Here is the thing that keeps economists like Maya MacGuineas from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget awake at night: interest.

For a long time, the debt was "cheap." Interest rates were near zero, so even though we owed $20 trillion, the monthly payments were manageable. But now? The Federal Reserve raised rates to fight inflation. Suddenly, the interest alone on our debt is costing more than our entire defense budget. We are essentially using a credit card to pay the interest on another credit card.

👉 See also: Syrian Dinar to Dollar: Why Everyone Gets the Name (and the Rate) Wrong

It’s a cycle that is incredibly hard to break because no politician wants to be the one to tell voters they have to either pay more in taxes or receive fewer benefits.

Real World Consequences of a Ballooning Chart

Does this actually matter to you? Honestly, it depends on who you ask.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) suggests that as long as a country prints its own currency, it can’t really "go bankrupt" in the way a person can. They argue that the only real limit is inflation. If the government prints too much money and there aren't enough goods to buy, prices skyrocket. Sound familiar?

On the other side, traditionalists argue that high debt "crowds out" private investment. If the government is sucking up all the available cash to fund its debt, there’s less money for businesses to innovate or for you to get a cheap mortgage.

- Inflation Risks: When the debt grows too fast, the value of the dollar can slip.

- Reduced Flexibility: If another crisis hits, does the US have the "room" to borrow another $5 trillion?

- Tax Pressures: Eventually, the "low tax" era might have to end to service the interest.

Misconceptions About Who We Owe

People love to say "China owns us" when they look at the US national debt historical chart. That’s not really true.

Most of our debt is actually owed to... us. The biggest holders of US debt are American citizens, pension funds, the Federal Reserve, and state governments. Foreign countries like Japan and China do hold trillions, but they aren't the majority owners. They buy our debt because, despite the scary-looking chart, US Treasury bonds are still considered the "gold standard" of safety in the global market.

If the world stopped trusting the US to pay its bills, the global economy would essentially cease to function. That’s the "too big to fail" reality we live in.

✨ Don't miss: New Zealand currency to AUD: Why the exchange rate is shifting in 2026

Where Do We Go From Here?

There is no easy fix. You can't just "cut waste" and solve a $34 trillion problem. Total "waste" is a tiny fraction of the budget. The real money is in Social Security, Medicare, and Defense. Cutting those is political suicide.

But looking at the historical trends, we know that the current trajectory isn't sustainable forever.

Actionable Steps for Your Own Finances

Since you can't control the federal budget, you have to control your own response to it.

1. Diversify Your Assets

If you’re worried about the long-term value of the dollar due to debt levels, don't keep all your eggs in one basket. Look into a mix of domestic stocks, international equities, and perhaps hard assets like real estate or gold.

2. Watch Interest Rates, Not Just the Debt

The debt total is a "scary headline" number, but the interest rate is what actually changes your life. When the government has to pay more for its debt, your mortgage and car loan rates usually stay higher too. Plan your big purchases around the Fed's movements.

3. Don't Panic-Sell

People have been predicting a "debt collapse" since the 1970s. It hasn't happened. The US economy is still the most productive engine on earth. Use the historical chart as a tool for context, not a reason to hide your cash under a mattress.

4. Vote with the Budget in Mind

If fiscal responsibility matters to you, look past the campaign slogans. Check out non-partisan sources like the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to see how proposed policies actually impact the long-term chart.

The US national debt historical chart tells a story of a country that has grown through crisis by leveraging its future. We've been here before, though never quite at this scale. Understanding the history helps you see that while the numbers are huge, the system is designed to carry weight—at least for now. Keep an eye on the interest payments; that’s the real metric that will tell us when the party is finally over.