Tax day is usually a headache for everyone, but for the biggest companies in America, the "sticker price" of their tax bill has swung wildly over the last century. If you look at the US corporate income tax rate history, it’s basically a roller coaster. We’ve gone from tiny single-digit percentages to a staggering 52% during the Cold War, and now we’re sitting at a flat 21%. But here’s the thing—hardly anyone actually pays the top rate. Between deductions, credits, and the magic of offshore accounting, the "effective rate" is the real metric that matters for the bottom line.

Most people think taxes only go up, but that’s just not true. Honestly, the corporate tax landscape today is unrecognizable compared to the 1950s. Back then, corporations were the primary engine funding the federal government. Today? Not so much.

The Early Days and the World War Spike

When the corporate tax first showed up in 1909, it was basically a rounding error. It was a 1% tax on net income over $5,000. Can you imagine? Just 1%. But then the 16th Amendment happened in 1913, giving Congress the actual power to tax income without worrying about population distribution.

Then came World War I. War is expensive. By 1918, the top rate spiked to 12% to help fund the military. It fluctuated through the Roaring Twenties, usually hovering around 10% to 13%, but the Great Depression changed the math entirely. President Herbert Hoover and later FDR needed cash to keep the country from collapsing. By the time we hit the 1940s and World War II, the top marginal rate for corporations hit 40%.

It stayed high. Really high.

The Era of the 50% Tax Rate

If you told a CEO today they had to hand over half their profits to Uncle Sam, they’d probably faint. But from 1951 until 1963, the top corporate tax rate sat at 52%. This was the era of the Korean War and the beginning of the massive infrastructure projects like the Interstate Highway System.

You’d think the economy would have choked under a 52% tax, right? Surprisingly, the 1950s are often cited as a golden age of American economic growth. One reason is that the tax code was full of holes—purposeful ones. Companies could write off massive investments in equipment and factories. It basically forced them to reinvest their money into the business rather than just handing it to shareholders or sitting on cash.

💡 You might also like: Why the Old Spice Deodorant Advert Still Wins Over a Decade Later

The Kennedy and Reagan Shifts

John F. Kennedy actually started the trend of bringing these rates down. He argued that lower rates could spur even more growth. By 1964, the rate dropped to 50%, then 48%. It stayed there for a long time.

Then came 1986.

The Tax Reform Act of 1986, signed by Ronald Reagan, was a massive deal. It slashed the top rate from 46% to 34%. This wasn’t just about being "pro-business." It was part of a global trend where countries were competing to attract capital. If your neighbor has a 30% tax and you have a 50% tax, the money is going to move. Simple as that.

Why the US Corporate Income Tax Rate History is Misleading

Here is the secret: the statutory rate (the one written in the law) and the effective rate (what they actually pay) are two different animals. According to data from the Tax Foundation and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the effective rate has been dropping for decades, even when the "official" rate stayed the same.

In 1993, the rate ticked up slightly to 35% under Bill Clinton. It stayed there for twenty-five years. On paper, the US had one of the highest corporate tax rates in the developed world. But if you looked at a company like General Electric or Apple during that time, they weren't paying 35%. They were using the "Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich"—a real, though now mostly defunct, accounting trick to move profits to low-tax havens.

The TCJA Earthquake of 2018

The biggest recent shift in US corporate income tax rate history happened with the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017. President Trump and Congress permanently slashed the corporate rate from 35% to a flat 21%.

📖 Related: Palantir Alex Karp Stock Sale: Why the CEO is Actually Selling Now

It was a total paradigm shift.

They also moved the US toward a "territorial" tax system. Before this, the US tried to tax American companies on money they made anywhere in the world. Now, we mostly just tax what they make here. The goal was to stop companies from keeping trillions of dollars offshore. Did it work? Sort of. A lot of money came back, but a lot of it went straight into stock buybacks instead of new factories.

Comparing the US to the Rest of the World

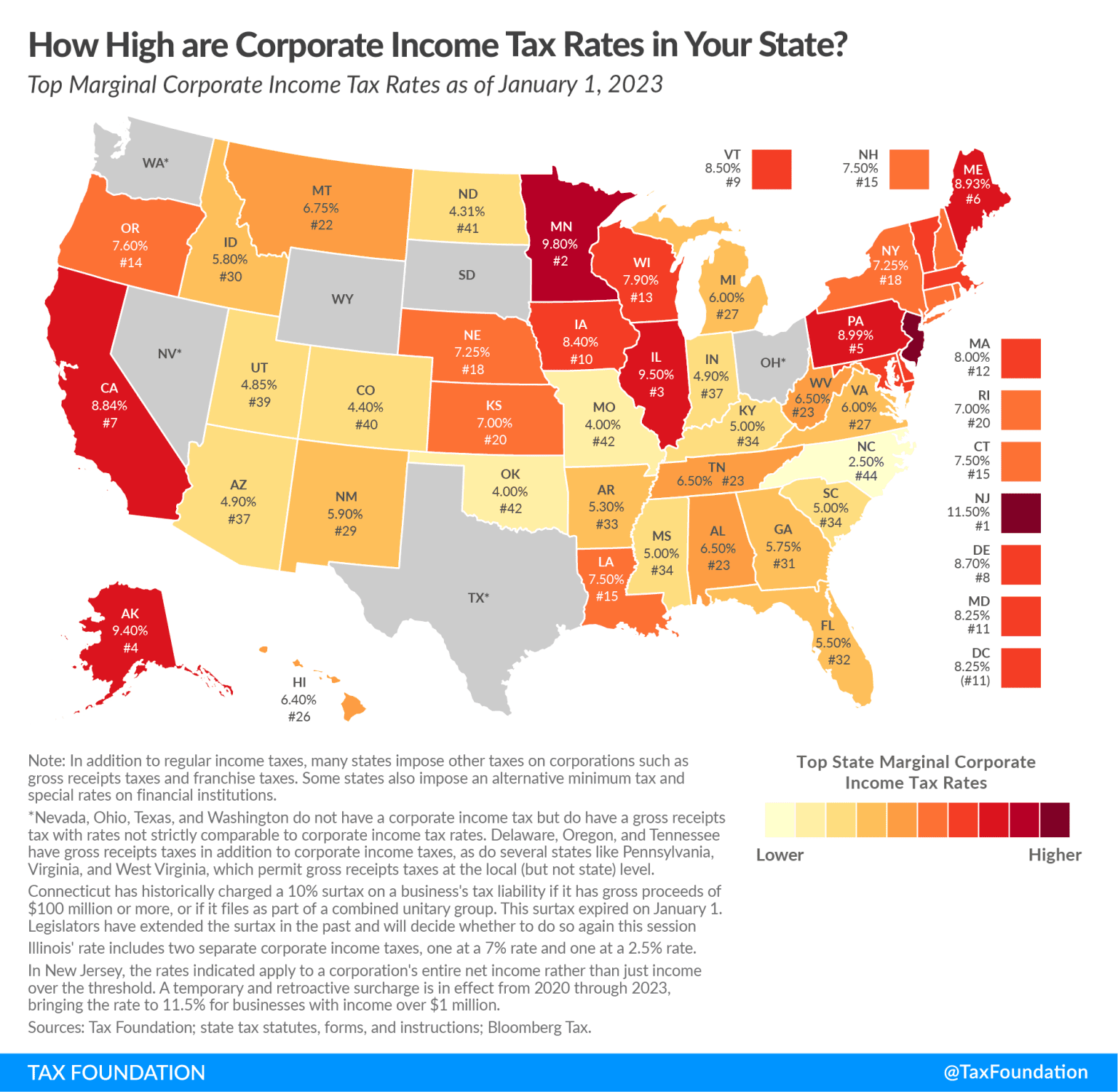

We don't live in a vacuum. For a long time, the US was the outlier with a high 35% rate. Now, at 21%, we’re pretty much in the middle of the pack for OECD countries.

- Ireland: 12.5% (The gold standard for low-tax hubs).

- United Kingdom: Recently raised theirs to 25%.

- Germany: Around 30% (when you add in local taxes).

- France: Roughly 25%.

It’s a race. If the US raises its rate to 28%—which has been a hot topic of debate in Washington lately—we might see another wave of "inversions" where companies try to move their headquarters abroad to save a few billion.

Real-World Impact: Does it actually help the economy?

Economists are split on this, and honestly, both sides have points. The "Supply-Side" folks argue that lower taxes lead to more investment, higher wages, and a bigger economy. They point to the post-2018 period where unemployment hit historic lows.

On the flip side, groups like the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) point out that many of the most profitable companies still pay next to nothing. In 2020, ITEP found that 55 of the largest corporations paid $0 in federal taxes despite billions in profit. They do this through R&D credits, depreciation on assets, and stock option tax breaks.

👉 See also: USD to UZS Rate Today: What Most People Get Wrong

So, when we talk about the history of these rates, we have to acknowledge the complexity. A 21% rate sounds lower than 35%, but if you close the loopholes at the same time, a company might actually end up paying more.

What Happens Next?

The 2017 tax cuts are a big part of the current deficit conversation. Some of the provisions in the TCJA are set to expire soon, though the 21% corporate rate is technically permanent unless a new law changes it.

There’s also the "Global Minimum Tax" led by the OECD. Over 130 countries have agreed in principle to a 15% minimum tax to stop the race to the bottom. If this actually becomes the global standard, the era of tax havens might finally be over.

Actionable Insights for Business Owners and Investors

Understanding the US corporate income tax rate history isn't just for history buffs. It affects how you should view your own financial strategy.

- Watch the "Effective" Rate: If you are investing in a company, don't just look at their revenue. Look at their 10-K filing to see their effective tax rate. If it's 5%, they are very good at using credits, but they are also at risk if the law changes.

- Leverage Section 179: Even with the 21% rate, small and medium businesses can often deduct the full price of equipment in the year they buy it. This is a carryover from the philosophy of the 1950s—encouraging reinvestment.

- Plan for Volatility: Tax laws are political. They change every time the White House changes parties. Don't build a 10-year business plan that relies entirely on a 21% tax rate staying forever.

- Monitor the OECD Minimum Tax: If you do business internationally, the 15% global floor is coming. This will change how you price products in different markets and where you choose to hold your intellectual property.

The history of taxes in America shows one thing clearly: the rate you see on the front page of the newspaper is rarely the rate that actually gets paid. Staying informed means looking past the 21% or 35% and seeing the machinery underneath.

To stay ahead, keep an eye on the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports. They provide the most objective data on how these tax shifts actually impact the federal deficit and the broader economy over long periods.