Pigs are basically our biological mirrors. It sounds a little weird, honestly, but when you look at how a pig's body handles fluids, you're essentially looking at a slightly sturdier version of yourself. This isn't just farm science. It's the backbone of modern regenerative medicine and urological research. If you've ever wondered why surgeons and researchers are so obsessed with urinary bladder pig function, it’s because their anatomy is the closest thing we have to a human model without actually being human.

The bladder isn't just a balloon.

Think of it as a highly sophisticated pressure-sensitive vault. In a pig, this organ has to manage massive shifts in volume while maintaining a watertight seal against some pretty acidic waste. It’s a powerhouse of smooth muscle and specialized lining.

What really happens inside: urinary bladder pig function and anatomy

The way a pig's bladder works is a masterclass in biomechanics. You have the detrusor muscle—this thick, interlaced web of smooth muscle fibers—that sits there, chilling, while the bladder fills. It’s got this incredible ability called "compliance." This means the bladder can expand significantly without the internal pressure rising too much. If the pressure spiked every time a little more urine entered, the pig (and you) would feel like they were in a constant state of emergency.

Pigs are large animals. Their bladders can hold a lot, often exceeding 500ml to 1 liter depending on the size of the hog.

The magic happens at the urothelium. This is the inner lining. It’s not just a skin; it’s a barrier. It’s made of "umbrella cells" that stretch out like tiny shields to prevent toxins in the urine from leaking back into the bloodstream. In the context of urinary bladder pig function, this barrier is nearly identical to the human version in terms of permeability and protein expression. That is why, when scientists want to test a new drug for interstitial cystitis or bladder cancer, they don't start with a mouse if they can help it. They look at the pig.

The three layers of the wall

First, you have the mucosa. It's the innermost part. It’s slick. It’s tough.

Then, there's the submucosa. This is where the "infrastructure" lives—blood vessels and nerves that tell the brain, "Hey, we're getting full back here."

✨ Don't miss: Why Do Women Fake Orgasms? The Uncomfortable Truth Most People Ignore

Finally, the muscularis propria. This is the muscle layer that actually does the squeezing. In pigs, this layer is particularly robust. Because pigs have a horizontal posture compared to our vertical one, the gravitational pressures on the bladder are different, yet the fundamental way the nerves trigger a contraction is remarkably similar to ours.

Why the medical world is obsessed with porcine bladders

You might have heard of "SIS" or Small Intestinal Submucosa, but the bladder has its own version: Porcine Urinary Bladder Matrix (UBM).

This is where things get wild.

Doctors realized years ago that if you strip away the actual pig cells—a process called decellularization—you’re left with a scaffold of collagen and growth factors. This extracellular matrix (ECM) is a miracle for wound healing. Because the urinary bladder pig function involves constant stretching and repairing, the tissue is naturally loaded with signals that tell the body to grow new blood vessels.

When a surgeon uses a patch made from a pig's bladder on a human patient, the human body doesn't just see it as a foreign object. It sees it as a blueprint. It crawls into that pig scaffold and starts building human tissue. It's used for everything from hernia repairs to rebuilding "shattered" limbs in military medicine. Dr. Stephen Badylak at the University of Pittsburgh has been a pioneer in this, showing that the "basement membrane" of the pig bladder can actually help regrow lost muscle mass.

It’s not just about the meat. It’s about the architecture.

Comparison with other models

- Mice: Too small. Their bladders empty through different neural pathways.

- Primates: Too expensive and ethically complex.

- Synthetic materials: Often cause inflammation. They don't "breathe" or grow with the patient.

- The Pig: Just right. The size, the thickness of the wall, and the way the nerves are distributed make it the "Goldilocks" of urological research.

The nervous system connection: How it actually fires

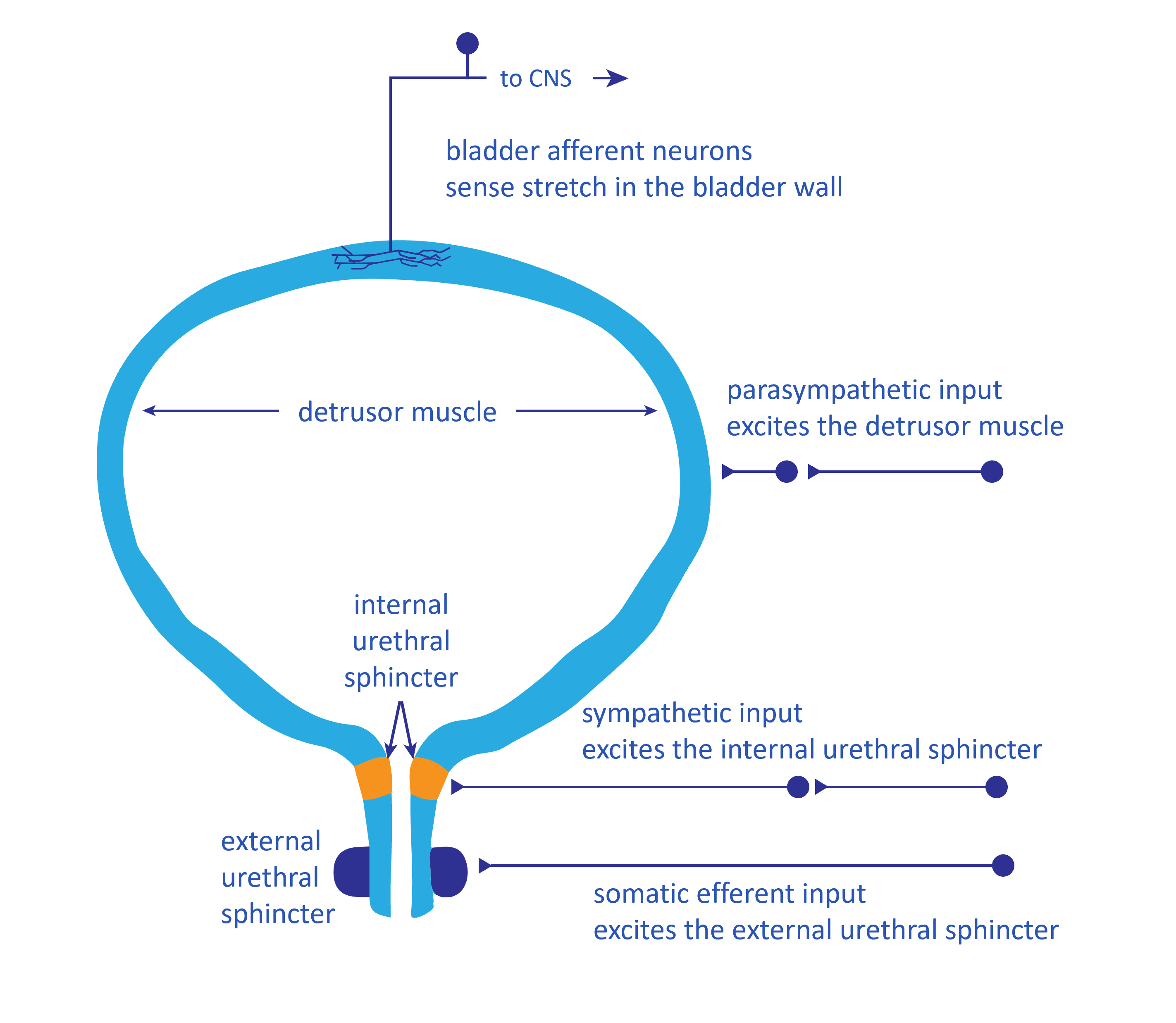

A bladder doesn't just empty because it's full. It empties because the brain gives it the green light. In pigs, this involves a complex dance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

🔗 Read more: That Weird Feeling in Knee No Pain: What Your Body Is Actually Trying to Tell You

When the bladder is filling, the sympathetic nerves keep the "exit door" (the sphincter) closed and the "squeezer" (the detrusor) relaxed. As the volume increases, stretch receptors start firing like crazy. These signals travel up the spinal cord. In a healthy urinary bladder pig function cycle, the pig eventually finds a spot, the parasympathetic system kicks in, the sphincter relaxes, and the detrusor contracts.

Interestingly, pigs can suffer from "overactive bladder" just like people. Researchers use this to test neuromodulation devices—basically pacemakers for the bladder. By stimulating the sacral nerves in a pig, scientists can figure out the exact electrical frequency needed to stop a human from having to run to the bathroom every twenty minutes.

Biomechanics and the "Stress-Strain" curve

If you took a piece of pig bladder and put it in a machine that pulls it apart (which scientists actually do), you’d see some fascinating physics.

The tissue is "viscoelastic."

This means it behaves somewhat like a liquid and somewhat like a solid. If you stretch it fast, it resists. If you stretch it slowly, it yields. This property is crucial for urinary bladder pig function because it allows the organ to accommodate a sudden influx of urine—say, after the pig drinks a ton of water—without rupturing.

The collagen fibers in the bladder wall are "crimped" like a spring. When the bladder is empty, they are coiled up. As it fills, they uncoil. Once they are fully straight, the bladder becomes very stiff, which is the physical signal that it's time to go. It’s a mechanical safety switch.

Real-world applications: Beyond the lab

We aren't just talking about theory here.

💡 You might also like: Does Birth Control Pill Expire? What You Need to Know Before Taking an Old Pack

- Tissue Engineering: Creating entire "bio-artificial" bladders using pig scaffolds seeded with human cells.

- Surgical Training: Resident surgeons often practice on pig bladders because the "tissue feel"—the way it resists a needle or tears under pressure—is the only way to truly prep for a human operating room.

- Drug Delivery: Testing "intravesical" therapies (drugs put directly into the bladder) to see how long they stay in the lining before being washed away.

There are limitations, obviously. Pigs grow fast. Their hormonal cycles are different, especially in sows, which can affect bladder capacity. Also, the immune response to pig tissue (even decellularized) has to be carefully managed, though the UBM products are generally very well-tolerated.

What most people get wrong about porcine urology

People think a bladder is just a storage tank. It’s actually an active sensory organ.

The cells lining the bladder (the urothelium) actually "taste" the urine. They can sense chemical changes and release signaling molecules like ATP to talk to the underlying nerves. When we talk about urinary bladder pig function, we're talking about a system that is constantly monitoring the chemical makeup of waste to ensure the body's internal balance remains stable.

It’s also not a "dumb" muscle. The detrusor muscle has "micromotions." Even when it's filling, small parts of the muscle are twitching and shifting to redistribute the load. It’s like a crowd of people shifting their weight so nobody gets tired of standing.

Actionable insights for those in research or health

If you’re looking at porcine models for urological health or regenerative medicine, keep these specific factors in mind:

- Source matters: The age and breed of the pig significantly change the thickness of the extracellular matrix. Younger pigs have more "growth factors," while older pigs have more "cross-linked" (tougher) collagen.

- Decellularization is key: If you're using bladder-derived scaffolds, the method of removing cells (detergents vs. enzymes) completely changes how the urinary bladder pig function is mimicked in the final product.

- Hydration impacts data: Just like humans, a pig's bladder wall health is directly tied to its hydration levels. Dehydrated porcine tissue loses its viscoelasticity, making it a poor model for surgical testing.

- Focus on the Trigone: Most bladder issues happen in the "trigone"—the triangular area where the tubes enter and exit. When studying pig bladders, this is the area with the highest density of nerves and the most complex blood supply.

Understanding the pig bladder isn't just for vets. It’s for anyone interested in how we might one day replace failing organs with biological "upcycles." The pig has given us a map. We’re just now learning how to read the finer details of the terrain.

To utilize this knowledge effectively, researchers should prioritize fresh tissue samples over frozen ones whenever testing mechanical properties, as ice crystals can micro-tear the delicate collagen "crimp" that gives the bladder its unique elasticity. For those looking into regenerative patches, verify the processing method of the UBM to ensure the basement membrane remains intact, as this is the specific layer responsible for true tissue regeneration rather than just scar formation.