Let’s be real. Most people can’t hear the name of the seventh planet without cracking a smile. It’s the ultimate cosmic joke. But if you actually look at the data coming from NASA’s Voyager 2 or the latest scans from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), you realize that Uranus facts are way more intense than a middle-school pun. We are talking about a giant, turquoise ball of gas and ice that literally rolls through space on its side. It’s a chemical oddity. It’s a gravitational puzzle. Honestly, it’s probably the most underrated thing in our neighborhood.

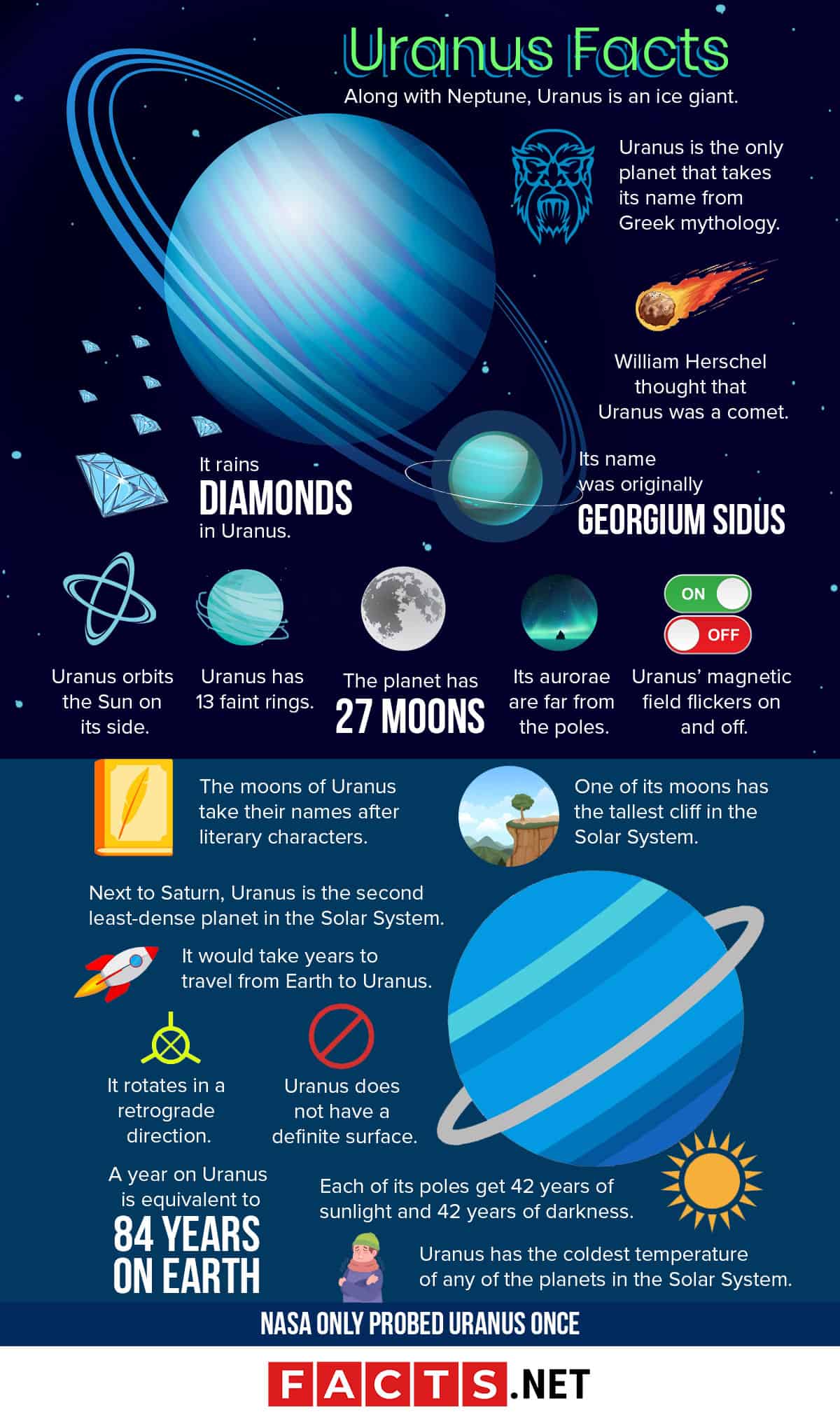

William Herschel found it in 1781. He actually thought it was a comet at first. Can you imagine? You're looking through a homemade telescope in your backyard in Bath, England, and you accidentally stumble upon a world 1.8 billion miles away. He wanted to name it "Georgium Sidus" after King George III. Thankfully, that didn’t stick. The scientific community went with Uranus, keeping the tradition of Greek and Roman deities.

The Physics of a Planet on its Side

Most planets spin like a top. Uranus spins like a rolling bowling ball. Its axial tilt is roughly 98 degrees. This means for about 21 years at a time, one pole is getting baked in continuous sunlight while the other is plunged into a dark, frozen nightmare. Scientists like Dr. Michele Bannister have suggested that a massive collision—likely an object twice the size of Earth—slammed into Uranus billions of years ago. This "megastrike" literally knocked the planet over.

Because of this tilt, the seasons are broken. If you lived at the north pole of Uranus, you’d have a single summer that lasts 21 Earth years. Then 21 years of autumn. Then 21 years of a brutal, pitch-black winter. It’s not just cold; it’s the coldest place in the solar system. Even though Neptune is further away from the sun, Uranus holds the record for the lowest temperature ever recorded: -224 degrees Celsius. It doesn't have an internal heat source like Jupiter or Saturn. It’s basically a dead battery floating in the void.

What’s Inside an Ice Giant?

We call it a gas giant, but that’s technically wrong. Astronomers prefer "Ice Giant."

Deep down, there’s likely a small, rocky core. But most of the mass is a hot, dense "fluid" of icy materials—water, methane, and ammonia. It’s not "ice" like the cubes in your freezer. It’s a super-pressurized, semi-solid slush. The methane is what gives the planet its signature cyan glow. Methane absorbs red light and reflects blue and green back at us.

The Diamond Rain Theory

This is where things get wild. In the deep layers of the atmosphere, the pressure is so intense that it can break apart methane molecules. This releases carbon, which then crystallizes.

💡 You might also like: Meta Black Friday Deals: Why the Quest 3S is Changing the Math This Year

- Imagine millions of carats of diamonds.

- They rain down through the mantle.

- They likely settle around the core.

- Laboratory experiments at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have actually simulated these conditions using high-powered lasers, proving that "diamond rain" isn't just sci-fi—it’s high-pressure physics.

A Ring System You Can’t See

Everyone loves Saturn’s rings. They’re flashy. But Uranus has 13 distinct rings of its own. They just happen to be incredibly dark. They’re likely made of water ice mixed with organic dark matter. The Epsilon ring, which is the brightest, is narrow and composed of boulders up to a few meters wide.

The rings were discovered almost by accident in 1977. James Elliot, Edward Dunham, and Jessica Mink were using the Kuiper Airborne Observatory to watch Uranus pass in front of a star. They noticed the star "blinked" before and after the planet passed. Those blinks were the rings blocking the starlight. It changed everything we knew about planetary evolution.

The Moons: A Shakespearean Cast

Usually, moons are named after Greek mythological figures. Not here. The 27 moons of Uranus are named after characters from William Shakespeare and Alexander Pope.

- Miranda is the weirdest. It looks like someone smashed it into pieces and glued it back together randomly. It has the tallest cliff in the solar system, Verona Rupes, which is 12 miles high. If you jumped off it, you’d fall for over 10 minutes before hitting the bottom.

- Titania is the largest. It’s covered in giant canyons and frost.

- Oberon is the outermost of the major moons, heavily cratered and old.

- Ariel has the brightest surface and shows signs of recent geological activity.

- Umbriel is the dark twin, reflecting very little light.

These moons aren't just rocks. They are potential "ocean worlds." Recent studies using data re-analysis from the 1980s suggest that four of these moons—Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon—might have internal oceans trapped under the ice. If there’s liquid water, there’s a conversation to be had about habitability.

Gravity and Atmosphere

If you could stand on the "surface" of Uranus (you can't, you'd sink into the slush), you’d feel about 89% of Earth’s gravity. Even though the planet is four times wider than Earth, it's not very dense. You'd actually feel lighter there than you do on Earth.

The wind is terrifying. We’re talking speeds of 560 miles per hour. That’s more than twice as fast as the strongest hurricane ever recorded on Earth. Because the atmosphere is mostly hydrogen and helium, your voice would sound incredibly high-pitched if you could somehow breathe and speak there. But you couldn't. The smell alone would kill the vibe. The upper atmosphere contains hydrogen sulfide—the same chemical that makes rotten eggs smell terrible.

The Mystery of the Magnetic Field

Uranus’s magnetic field is a total mess. On Earth, our magnetic poles roughly align with our geographic poles. On Uranus, the magnetic field is tilted 60 degrees away from the axis of rotation. Even weirder, it doesn't pass through the center of the planet. It’s offset by a third of the planet's radius.

Why? We don't really know. One theory is that the magnetic field is generated by a convection current in a shallow layer of electrically conducting water (a "water-ammonia ocean") rather than in the core. It makes the magnetosphere wobble like a lopsided top as the planet rotates.

🔗 Read more: Smart Rear View Mirror: Why Your Car Needs Better Eyes Than Yours

Exploration: Why haven't we gone back?

We have only visited Uranus once. Voyager 2 flew by in January 1986. Everything we know in high detail comes from those few days of data. Since then, we’ve relied on the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based observatories.

In 2022, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released a "decadal survey." They listed a mission to Uranus as the highest priority for the next decade of space exploration. We need a "Uranus Orbiter and Probe." We need to drop a sensor into that atmosphere to see what’s actually happening under those clouds.

- The flight would take 12 to 15 years.

- It would require a gravity assist from Jupiter.

- The probe would measure isotopes to tell us exactly where in the solar system Uranus formed.

Surprising Tidbits You Probably Didn't Know

Uranus is actually visible to the naked eye. If you have a perfectly dark sky and you know exactly where to look, you can see it without a telescope. It just looks like a very faint, dim star. This is why ancient astronomers missed it—they assumed it was just another star because it moves so slowly through its orbit. One year on Uranus is 84 Earth years. If you were born there, you likely wouldn't live to see your first birthday.

The planet’s mass is about 14.5 times that of Earth. It’s the "lightweight" of the giants. Despite being huge, it's the least massive of the outer planets.

Its density is only 1.27 grams per cubic centimeter. For context, water is 1.0. This means Uranus is only slightly denser than water. If you had a bathtub the size of a solar system, Uranus would almost float (but not quite as well as Saturn would).

Why This Planet Matters for Exoplanets

When we look at stars outside our solar system, we find "sub-Neptunes" and "ice giants" more than anything else. By studying Uranus, we are basically studying the most common type of planet in the universe. Understanding its weird magnetic field and its lopsided tilt helps us understand how solar systems form everywhere.

Is there life? Almost certainly not. The temperatures and pressures are too extreme for the biology we understand. But the moons? That's a different story. Any place with liquid water and internal heat is a candidate for further investigation.

Fast Facts for Your Next Trivia Night

- Distance from Sun: About 2.9 billion kilometers.

- Diameter: 51,118 km (roughly 4 Earths).

- Day Length: 17 hours and 14 minutes.

- Atmosphere: Mostly Hydrogen and Helium, with a dash of Methane.

- Total Moons: 27 confirmed.

- Discovery Date: March 13, 1781.

- First (and only) Spacecraft Visit: Voyager 2.

The cloud layers are segregated by temperature. The lowest clouds are thought to be water ice, while the higher ones are ammonium hydrosulfide and the topmost are methane ice. It's a vertical stack of different chemicals.

Actionable Insights for Amateur Astronomers

If you want to see Uranus yourself, you don't need a NASA budget, but you do need patience.

- Use a Sky Map App: Apps like Stellarium or SkyGuide are essential. Uranus moves so slowly that it stays in the same constellation for years.

- Get Binoculars: A pair of 10x50 binoculars will show Uranus as a tiny, slightly bluish-green dot. It won't look like a disc; it'll look like a "star" that doesn't twinkle quite right.

- Wait for Opposition: This is when Earth is directly between the Sun and Uranus. The planet is at its brightest and closest.

- Find Dark Skies: Light pollution is the enemy. Get away from city lights to see that subtle cyan hue.

The next step for humanity is a dedicated mission. Until then, we keep staring through the lens of the JWST, trying to figure out why this giant ball of ice decided to tip over and freeze while the rest of the solar system stayed upright. It’s a reminder that space is messy, violent, and incredibly strange.

To dig deeper into the actual raw data, check out the NASA Solar System Exploration page or the recent publications from the Planetary Science Decadal Survey. These sources provide the peer-reviewed backbone for why we are likely headed back to the seventh planet by the late 2030s.