Most people treat the up and down plank like a race. You’ve seen them in the corner of the gym, flailing their arms and rocking their hips like they’re trying to shake off an invisible attacker. It’s chaotic. It’s loud. And honestly? It’s basically useless if the goal is actual core strength. If your hips are swaying side to side every time you move from your elbows to your hands, you aren't doing a core exercise anymore; you’re just doing a clumsy dance on a yoga mat.

The up and down plank, often called the "commandos" or "plank walks" in high-intensity circles, is a brutal hybrid. It combines the static tension of a standard plank with the dynamic shoulder stability of a push-up. But there’s a massive gap between doing it and doing it well. When you rush the movement, you let momentum take over, which effectively turns off your transverse abdominis—the deep core muscle that actually keeps your spine safe.

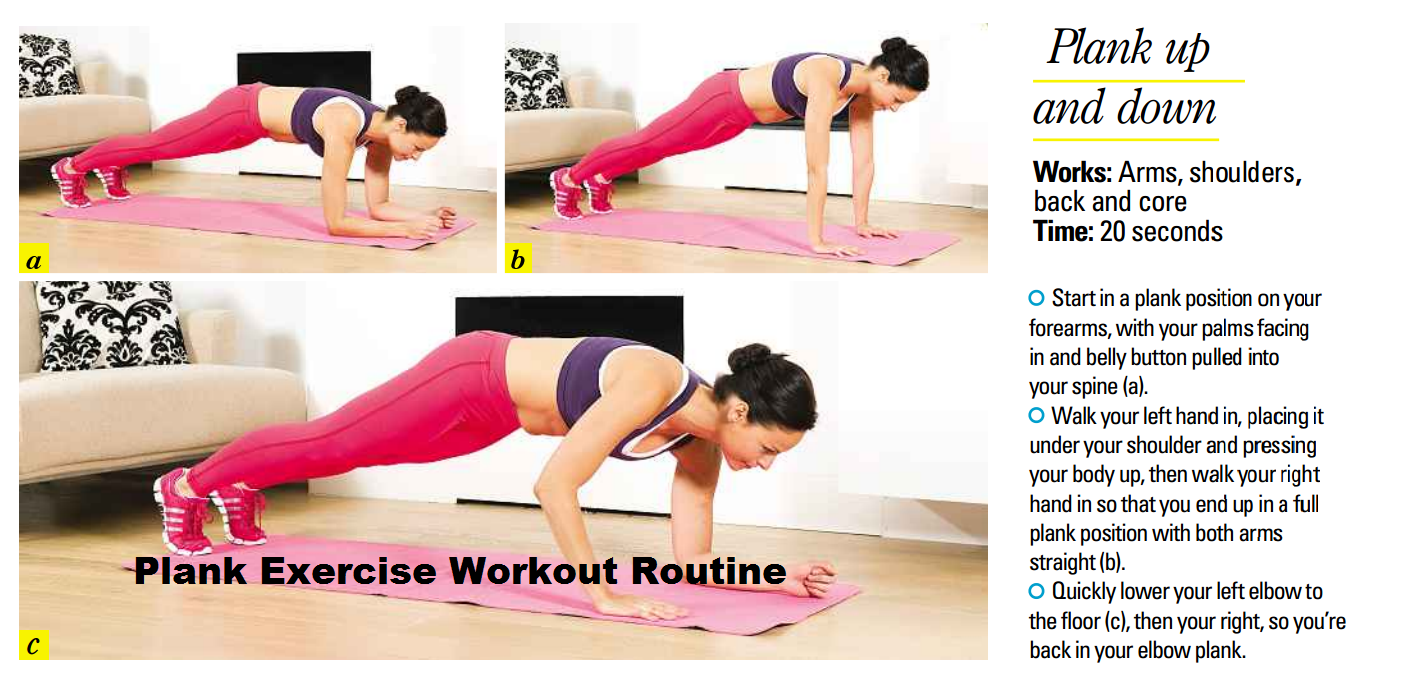

The Biomechanics of the Up and Down Plank

Let’s get nerdy for a second. The up and down plank is technically an "anti-rotational" exercise. While you are moving vertically, the real work is happening horizontally. Your body wants to tip over as soon as you lift one arm to transition. To stop that tip, your obliques and deep core have to fire like crazy.

Dr. Stuart McGill, a world-renowned expert in spine biomechanics at the University of Waterloo, has often pointed out that the spine’s best friend is stiffness. Not stiffness in a "I can’t touch my toes" way, but in a "my torso is a solid block of granite" way. When you perform an up and down plank, you are challenging that stiffness. Every time you transition from your forearm to your palm, you’re creating a moment of instability. If your belly drops or your butt spikes into the air, you’ve lost the battle.

Why the "Hustle" Mentality Fails

In many HIIT classes, the instructor yells for "more reps." This is the death of good form. In a study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, researchers found that as fatigue sets in during dynamic core tasks, the recruitment of the primary stabilizers drops significantly, and the body begins to compensate with the lower back (lumbar spine).

✨ Don't miss: Forehead Fillers Gone Wrong: Why This Particular Treatment Can Get Ugly Fast

Basically, if you do 50 sloppy up and down planks, you’re just training your lower back to take a beating. That’s why you feel that weird ache in your spine after a workout instead of a burn in your abs.

Common Mistakes That Kill Your Progress

You've probably done these. We all have.

The "Elvis Hips." This is the most common sin. Your hips should stay parallel to the floor the entire time. If they are swiveling left and right as you move, you're bypassing the core and just using your hip flexors and momentum.

Hand Placement. When you move from the elbow to the hand, where do you put your hand? Most people put it way out in front of their face. Wrong. To protect your rotator cuff and maximize tricep engagement, your hand needs to land exactly where your elbow just was. Right under the shoulder.

Neck Tension. Stop looking at your toes. Or the clock. When you crane your neck, you break the "neutral spine" alignment. Look at a spot about six inches in front of your hands. It keeps the cervical spine in line with the rest of your back.

Real-World Variations That Actually Work

If you’ve mastered the basic up and down plank, don't just add more time. That's boring.

The Weighted Commando: Throw a small sandbag or a 5lb plate on your mid-back. If the plate slides off, your hips are moving too much. It’s an instant feedback tool. It forces you to be slow.

The "Pause" Method: When you reach the top (the high plank), hold for three seconds. When you reach the bottom (the forearm plank), hold for three seconds. Removing the "flow" makes it twice as hard because you can't use the bounce from your tendons to get back up.

Slow-Motion Transitions: Try taking a full five seconds to move from the bottom to the top. It’s agonizing. It also builds incredible shoulder stability.

Is it Better Than a Standard Plank?

It depends. A static plank is great for building endurance, but the up and down plank adds a functional element. Life isn't static. You’re constantly moving, lifting, and shifting weight. This exercise mimics those real-world demands.

However, it’s also harder on the joints. If you have "clicky" shoulders or wrist issues like carpal tunnel, the constant transition can be inflammatory. In those cases, a static plank or a "Dead Bug" exercise might actually be a better use of your time. You have to listen to your body. Pain is a signal, not a challenge.

👉 See also: Understanding Your Positive Strep Test Picture: What Those Red Lines Actually Mean

The Impact on the Serratus Anterior

One often overlooked benefit of the up and down plank is the activation of the serratus anterior—that "boxer’s muscle" that sits on your ribs. This muscle is crucial for healthy shoulder blade movement. As you press up from the floor, you're performing a protraction of the scapula. This strengthens the muscles that keep your shoulders from rounding forward, which is a godsend for anyone who sits at a desk all day.

How to Program This Into Your Routine

Don't do these every day. Your core muscles need recovery just like your biceps do.

- For Beginners: Aim for 3 sets of 10 controlled reps (5 leading with the right arm, 5 with the left). Focus entirely on "quiet hips." If someone placed a cup of water on your back, would it spill?

- For Intermediate/Advanced: Use it as a "finisher" at the end of a chest or shoulder day. Try 45 seconds of work followed by 15 seconds of rest, for 4 rounds.

- The Pro Tip: Always alternate your "leading" arm. If you always push up with your right hand first, you'll end up with a weird strength imbalance. Left, then right. Right, then left. Keep it even.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Workout

To get the most out of the up and down plank, stop thinking of it as an "abs" move and start thinking of it as a "total body tension" move.

First, squeeze your glutes. Hard. Like you're trying to hold a coin between your butt cheeks. This locks your pelvis in place and prevents that painful lower-back arch.

Second, drive your heels back. This engages your quads and calves, creating a "long" line of tension from your head to your heels.

Third, when you're on your forearms, don't clench your fists. Keep your palms flat on the floor. It sounds minor, but clenching your fists sends a signal to your brain to tighten the neck and jaw. Keeping your hands flat helps keep the tension where it belongs: in your midsection.

Finally, record yourself. Set your phone up on the floor and film one set from the side. You'll probably be surprised. What feels like a straight line is often a sagging bridge or a mountain peak. Adjust based on the video, not your feelings. Quality over quantity, every single time.