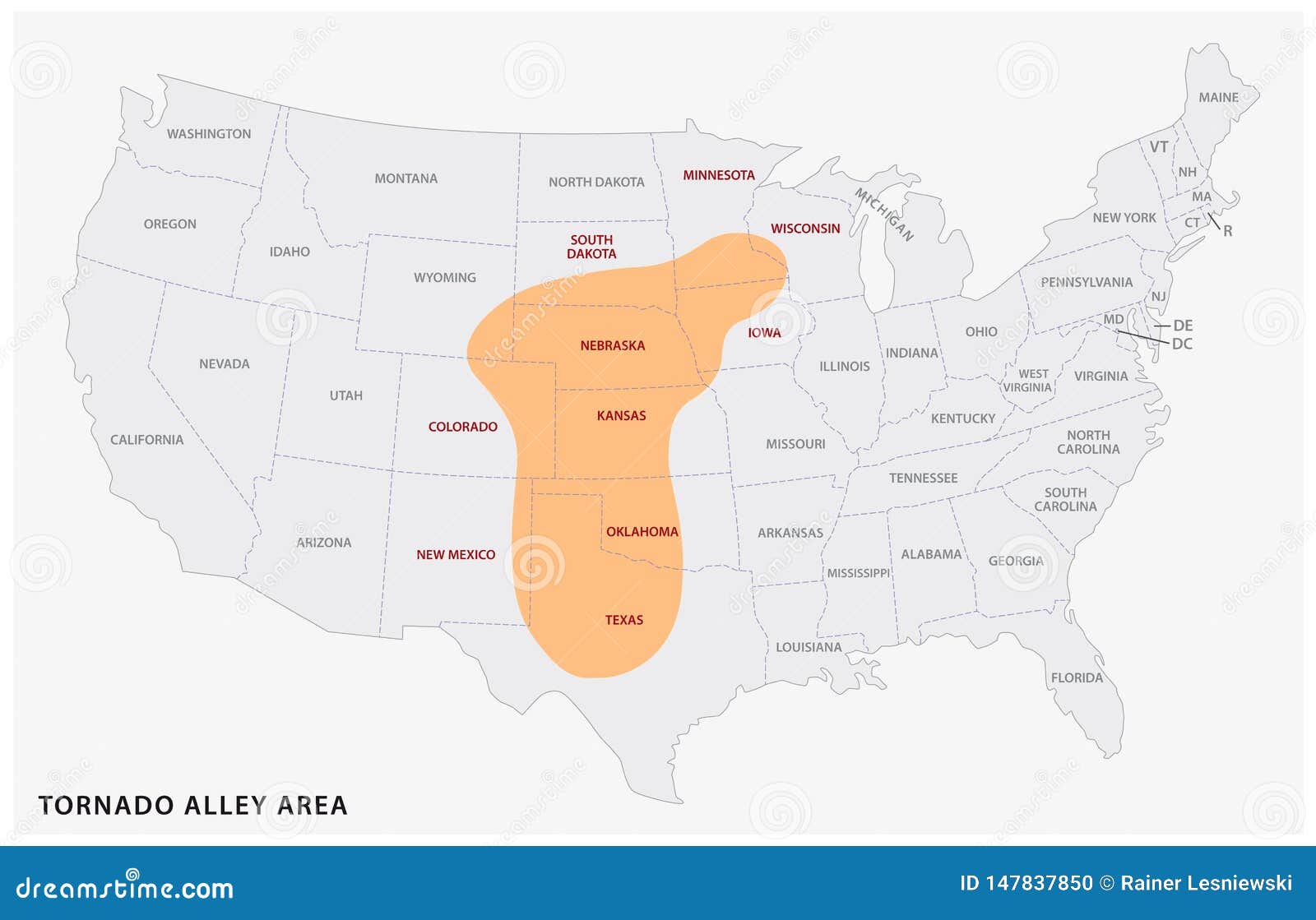

You’ve seen the movies. The dusty plains of Kansas, a lone farmhouse, and a terrifying funnel cloud roaring across the horizon. For decades, the United States map tornado alley was a fixed idea in our collective heads. We pointed to Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska and said, "That’s where the monsters live."

But the map is lying to you. Or at least, it’s out of date.

Nature doesn't care about our neat little boxes. While the traditional "Alley" remains a high-risk zone, the real danger is creeping toward the Mississippi Valley and the Southeast. This isn't just a minor tweak to a graphic on the evening news. It’s a massive geographic shift that puts millions more people in the path of violent, fast-moving storms.

The Classic United States Map Tornado Alley: A Legend Under Pressure

If you look at a historical United States map tornado alley, the heart of the action sits right in the Great Plains. Meteorologically, this happened because of a perfect, violent recipe. Dry, cool air from the Rockies crashes into warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico. Right in the middle? The dryline.

This is where the supercells used to congregate.

Oklahoma City is often cited as the most "hit" city in America. Between 1890 and today, over 150 tornadoes have touched down within the city limits. That’s a staggering density. Dr. Harold Brooks from the National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL) has spent years tracking these patterns. His data shows that while the Plains still get plenty of twisters, the frequency of big outbreaks is staggering elsewhere now.

Why is the classic map failing us?

Basically, the "Alley" was never an official term coined by the National Weather Service. It was popularized by two U.S. Air Force meteorologists, Robert Miller and Ernest Fawbush, back in 1952. They were trying to describe where the most intense activity happened. Over time, the media grabbed the term and wouldn't let go. It became a brand.

But the climate is changing, and so is the geography of risk.

The Dixie Alley Expansion

The most significant change to the United States map tornado alley isn't a disappearance of storms in the West; it's an explosion of activity in the East. Specifically, the Southeast. Meteorologists often call this "Dixie Alley."

Think Alabama. Mississippi. Tennessee.

👉 See also: Statesville NC Record and Landmark Obituaries: Finding What You Need

These states are seeing a measurable increase in "tornado days" over the last twenty years. Research led by Victor Gensini of Northern Illinois University has highlighted this eastward shift. His studies show a downward trend in the central plains and a sharp upward tick in the Midwest and Southeast.

It’s a different kind of danger here.

In Kansas, you can see a tornado coming from miles away. The terrain is flat, and the air is often clearer. In Alabama or Mississippi, you’re dealing with hills and heavy forest cover. You can't see the storm until it's on top of you. Plus, the storms in the Southeast are frequently "rain-wrapped." They look like a wall of water rather than a distinct funnel.

Then there’s the timing.

Plains tornadoes are often afternoon events—climaxing between 4 PM and 9 PM. In the Southeast, nocturnal tornadoes are terrifyingly common. A tornado at 3 AM is exponentially more lethal because people are asleep and don't hear the sirens or phone alerts. When you look at a United States map tornado alley today, the "hot zone" for fatalities is actually centered more over Memphis and Birmingham than it is over Wichita or Amarillo.

Why the Map is Changing

Atmospheric science is messy. Honestly, anyone who tells you they know exactly why the shift is happening is probably oversimplifying. But there are leading theories.

One major factor is the expansion of the "Dry Line." This is that boundary between moist Gulf air and dry desert air. Historically, it hung out over West Texas and Western Kansas. Lately, that boundary has been nudging eastward. When that line moves, the "convective potential" moves with it.

Climate change plays a role, though maybe not in the way you think. It isn't necessarily making more tornadoes. It's making the environments that support them more frequent in new places. Warm, moist air from the Gulf is reaching further north and further east, more often, especially in the winter and early spring.

Remember the December 2021 outbreak?

A massive tornado tore through Mayfield, Kentucky, and stayed on the ground for nearly 165 miles. That happened in December. In Kentucky. If you were looking at a traditional United States map tornado alley from the 1970s, you wouldn't expect a catastrophic EF4 event there in the dead of winter. That event was a wake-up call for many who still think of "Tornado Alley" as a May/June phenomenon in the Plains.

✨ Don't miss: St. Joseph MO Weather Forecast: What Most People Get Wrong About Northwest Missouri Winters

Infrastructure and Vulnerability

When we talk about the United States map tornado alley, we have to talk about people. Risk isn't just about where the wind blows; it’s about what the wind hits.

The Plains are sparsely populated. If a tornado hits an empty wheat field in rural Nebraska, it’s a scientific curiosity. If that same tornado hits a densely packed suburb in the suburbs of Atlanta or Nashville, it’s a national tragedy.

The Southeast has a much higher population density than the Great Plains.

There's also the issue of housing. Mobile homes are significantly more common in the "New Tornado Alley" states. According to NOAA data, mobile homes account for a disproportionate number of tornado-related deaths. Even a relatively weak tornado can be fatal in a structure that isn't anchored to a permanent foundation. This makes the eastward shift of the United States map tornado alley a massive public health crisis, not just a weather curiosity.

The Problem with "Alley" Language

There’s a growing movement among weather experts to ditch the "Alley" terminology altogether. Why? Because it gives people outside those zones a false sense of security.

If you live in Pennsylvania or New York, you might think you're "safe." But the truth is, every single one of the lower 48 states has had a tornado. Just look at the 2021 remnants of Hurricane Ida—it dropped destructive tornadoes in New Jersey.

The United States map tornado alley should really just be a map of the entire eastern two-thirds of the country.

Real-World Survival: What the Shift Means for You

If you're looking at a United States map tornado alley because you're planning a move or just trying to understand your own risk, don't focus on the shaded orange boxes from your 5th-grade geography book.

Focus on your local environment.

The shift east means we have to rethink building codes. In the Midwest, basements are standard. In the South, because of the high water table, nobody has a basement. People rely on interior closets or bathtubs. Is that enough? Probably not for an EF4 or EF5. This has led to a surge in "Safe Room" installations—reinforced concrete or steel boxes bolted to a garage floor.

🔗 Read more: Snow This Weekend Boston: Why the Forecast Is Making Meteorologists Nervous

The "New Alley" also requires better communication.

In a state like Oklahoma, people are "weather-aware" by birth. They know the names of the local meteorologists. They have multiple ways to get alerts. In the "new" high-risk zones, that culture is still catching up. If you find yourself in the expanding footprint of the United States map tornado alley, you need a redundant alert system. A weather radio isn't "old school"—it’s a literal lifesaver when the power goes out and cell towers are down.

Mapping the Future

We are likely going to see the "center of mass" for tornado activity continue its slow trek toward the Mississippi River. The 2024 and 2025 seasons have already shown significant activity in the Ohio Valley.

Does this mean Kansas is safe? No way.

It just means the risk is spreading. The United States map tornado alley is becoming less of an "alley" and more of a "neighborhood." A very big, very dangerous neighborhood.

Scientists like Dr. Walker Ashley have been vocal about the "Expanding Bullseye." As our cities grow larger and take up more space, the chance of a tornado hitting a populated area increases, regardless of whether there are "more" tornadoes or not. We are essentially building bigger targets.

Taking Action on Your Local Risk

Stop thinking about Tornado Alley as a place you visit on a storm-chasing tour. If you live anywhere east of the Rockies, the United States map tornado alley includes you to some degree.

First, get a NOAA Weather Radio. It sounds boring. It is boring. Until it’s 2 AM and a tornado is moving at 60 mph toward your house. Apps are great, but they rely on the internet and cell service, both of which are the first things to fail in a major storm.

Second, identify your "safe place" today. Not when the sirens go off. Today. If you don't have a basement, you need an interior room on the lowest floor, away from windows. Put a pair of sturdy shoes in that spot. People often forget that after a tornado, the ground is covered in glass and nails. You can't escape if your feet are shredded.

Third, check your insurance. Many homeowners are surprised to find their "windstorm" coverage has high deductibles or specific exclusions in high-risk zones.

The United States map tornado alley is a living document. It’s shifting, stretching, and becoming more unpredictable. Stay weather-ready, ignore the outdated maps, and respect the fact that the atmosphere doesn't follow state lines.

Keep your eye on the sky, but keep your plan on the ground. Be ready for the "New Alley" long before the clouds start to rotate. Proper preparation usually means the difference between a scary story and a tragedy. Make sure you're on the right side of that line.