You’re watching a freight train crawl at five miles per hour. It looks slow, almost lazy. But if that train hits a car stalled on the tracks, the car is basically deleted. Now, imagine a tiny 9mm bullet. It weighs almost nothing, yet it can punch through solid wood. Why? Because of momentum. But here’s the thing that trips everyone up in high school science: how do we actually measure that "oomph"? The unit of momentum in physics isn't some fancy named unit like the Newton or the Joule. It’s a bit of a mouthful, but once you break it down, it tells you exactly what’s happening in the physical world.

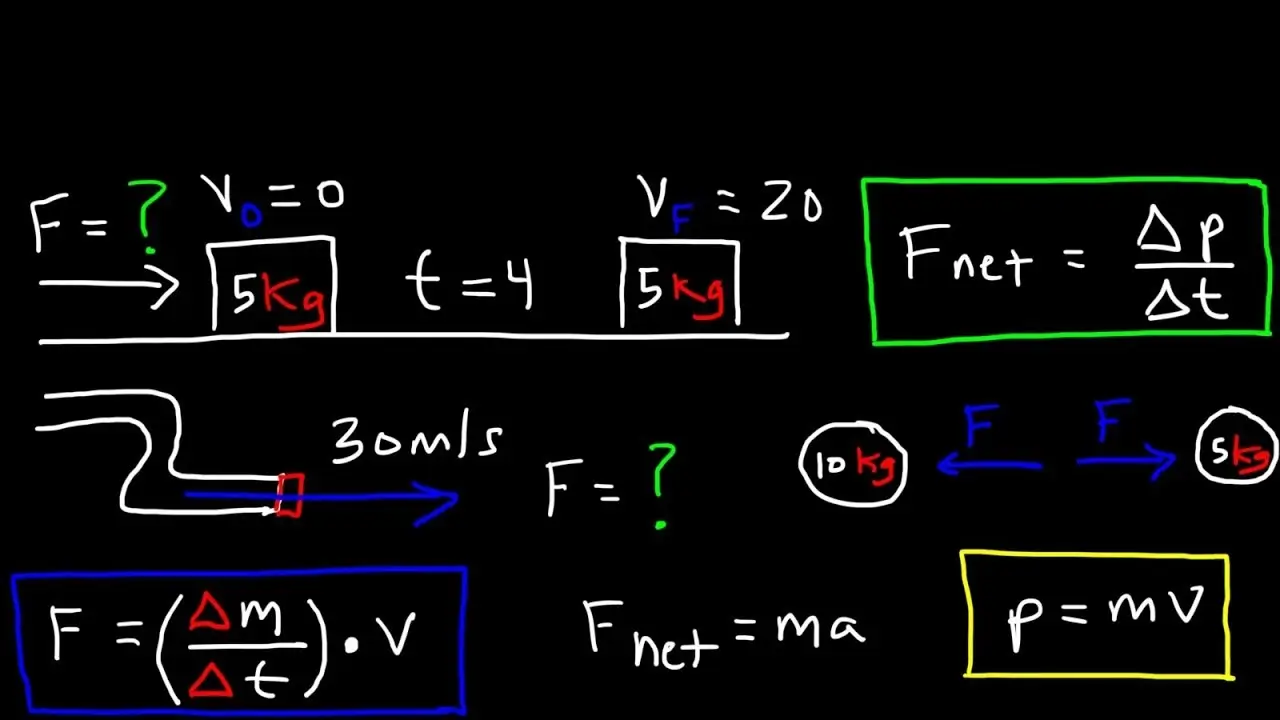

Momentum is the "quantity of motion." If it’s moving and it has mass, it has momentum. To find the unit, we just look at the recipe. Momentum ($p$) is mass ($m$) times velocity ($v$). In the International System of Units (SI), mass is measured in kilograms (kg) and velocity is measured in meters per second (m/s). You just smash them together.

The result? The kilogram-meter per second, written as kg·m/s.

The Anatomy of the kg·m/s

It’s not a "glamour" unit. When you talk about force, you say Newtons. When you talk about energy, you say Joules. But momentum just sits there with its hyphenated name. Honestly, it’s better this way because it’s transparent. It tells you that if you double the weight of a bowling ball, you double the momentum. If you double the speed, you also double the momentum.

Think about a 1,000 kg car moving at 20 m/s. The math is simple: $1,000 \times 20 = 20,000$ kg·m/s. That number represents a physical reality. It tells you how hard it’s going to be to stop that car. If you tried to stop it with a wall, the wall has to absorb all 20,000 units of that momentum.

💡 You might also like: SpaceX Fractional Shares Blockchain: Why Everyone Is Suddenly Talking About rSpaceX

Does it have another name?

Actually, yeah. There’s a "secret" second unit that physicists use all the time, especially when talking about crashes or rockets. It’s the Newton-second (N·s).

Through some algebraic wizardry involving Newton’s Second Law ($F = ma$), you can prove that $1 \text{ kg}\cdot\text{m/s}$ is exactly the same as $1 \text{ N}\cdot\text{s}$. This usually comes up when we talk about Impulse. If you’ve ever watched a slow-motion video of a golf club hitting a ball, you’ve seen impulse in action. The club applies a force for a tiny fraction of a second.

$Force \times Time = Change \text{ in } Momentum$

So, if a golfer hits a ball with 500 Newtons of force for 0.01 seconds, the impulse is 5 N·s. And since impulse equals the change in momentum, the ball just gained 5 kg·m/s of momentum. They are two sides of the same coin.

Why Scale Matters in the Real World

We don't always use kilograms. If you’re a particle physicist working at CERN, measuring a subatomic particle in kilograms is like measuring the length of a flea in miles. It’s technically possible, but the numbers are stupidly small.

In the world of the very small, scientists often use units like electronvolt-seconds per meter (eV·s/m) or even just MeV/c. This comes from Einstein’s famous $E=mc^2$. It’s weird, but in high-energy physics, mass and energy are so intertwined that it’s easier to measure momentum in terms of the speed of light ($c$).

On the flip side, if you're talking about massive astronomical bodies, like a comet hitting a planet, you’re dealing with numbers so large they lose all meaning to the human brain. But the unit of momentum in physics stays the same. Whether it’s a photon or a galaxy, the kg·m/s is the universal yardstick.

📖 Related: Fast CO2 Dragster Designs: Why Most Students Still Build Slow Cars

The Common Traps: Momentum vs. Kinetic Energy

This is where people get confused. Both involve mass and velocity. Both describe a moving object. But they are not the same thing.

- Momentum is $mv$ (Mass $\times$ Velocity). It is a vector. This means direction matters. If two cars with the same momentum hit each other head-on, their total momentum is zero because one is positive and one is negative. They cancel out.

- Kinetic Energy is $\frac{1}{2}mv^2$. It is a scalar. Direction doesn't matter. Energy doesn't cancel out; it just turns into heat, sound, and twisted metal.

If you triple your speed, your momentum triples. But your kinetic energy? That increases by nine times (because of the square). This is why speeding is so dangerous. A small increase in velocity leads to a massive increase in the energy that needs to be dissipated in a crash, even though the momentum growth is linear.

Momentum in Sports: The "Heavy Hitter"

Ever wonder why a 250-pound linebacker is scarier than a 180-pound safety, even if they run the same speed? It’s the unit.

Let's look at a real-world example.

A rugby player weighing 100 kg sprinting at 8 m/s has a momentum of 800 kg·m/s.

To stop him dead in his tracks in one second, you need to apply 800 Newtons of force.

If you weigh only 70 kg, you have to be moving significantly faster—about 11.4 m/s—just to have the same momentum. If you're moving slower than that, you're the one who’s going to get pushed backward. It’s literal physics.

Practical Next Steps for Mastering Momentum

If you’re trying to actually apply this—whether for a physics exam or just to understand the world better—don't just memorize "kg·m/s." Try these mental exercises:

- Check your dimensions: Every time you see a momentum problem, verify that you have a mass unit and a velocity unit. If someone gives you grams, convert to kilograms first. If they give you kilometers per hour, convert to meters per second.

- Vector visualization: Always draw an arrow. Since the unit of momentum in physics is a vector unit, the direction is part of the answer. If a ball hits a wall and bounces back, its momentum changed from positive to negative. That’s a huge "delta" or change.

- The Impulse Link: Remember that $N\cdot s = kg\cdot m/s$. If you know how long a force was applied, you know the momentum change. This is how engineers design airbags. They can't change the momentum of your head (that’s fixed by your speed and weight), but they can increase the time it takes to stop, which lowers the force required.

Understanding momentum isn't just about passing a test. It’s about recognizing the "invisible weight" that objects carry when they move. The next time you see a heavy truck or a fast-moving ball, think about those kilograms-meters per second. It’s the invisible force that rules every collision in the universe.

To dive deeper, look into the Law of Conservation of Momentum. It’s the reason rockets can fly in the vacuum of space (where there's nothing to "push" against) and why ice skaters spin faster when they pull their arms in. Momentum isn't just a math problem; it's the fundamental rule of how stuff moves.