You’re probably used to thinking of "life" as things you can actually see. Dogs, oak trees, your annoying neighbor, the mold growing on that bread you forgot in the pantry—these are all multicellular giants. But honestly, if you look at the sheer numbers, they’re the outliers. Most of the life on Earth is invisible. It’s single-celled. When we talk about the meaning of unicellular organisms, we aren't just talking about a biology textbook definition; we’re talking about the original blueprint for survival that has outlasted every dinosaur and ice age.

It’s wild to think about. A single cell does everything. It eats. It breathes. It poops. It reproduces. It senses the world around it. All within one tiny membrane. No lungs, no heart, no brain. Just a self-contained biological machine that works perfectly.

What it actually means to be unicellular

Basically, a unicellular organism is a living thing that consists of only one cell. That’s it. That one cell is the entire body. While you have specialized cells—neurons for thinking, muscle cells for moving, blood cells for hauling oxygen—a unicellular organism is a generalist. It has to be a jack-of-all-trades.

Biologists usually split these into two main camps: Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes.

Prokaryotes are the old-school version. Bacteria and Archaea. They don’t have a nucleus. Their DNA just kinda floats around in the cytoplasm like loose spaghetti in a bowl. They’ve been around for roughly 3.8 billion years. To put that in perspective, humans have been here for a blink of an eye.

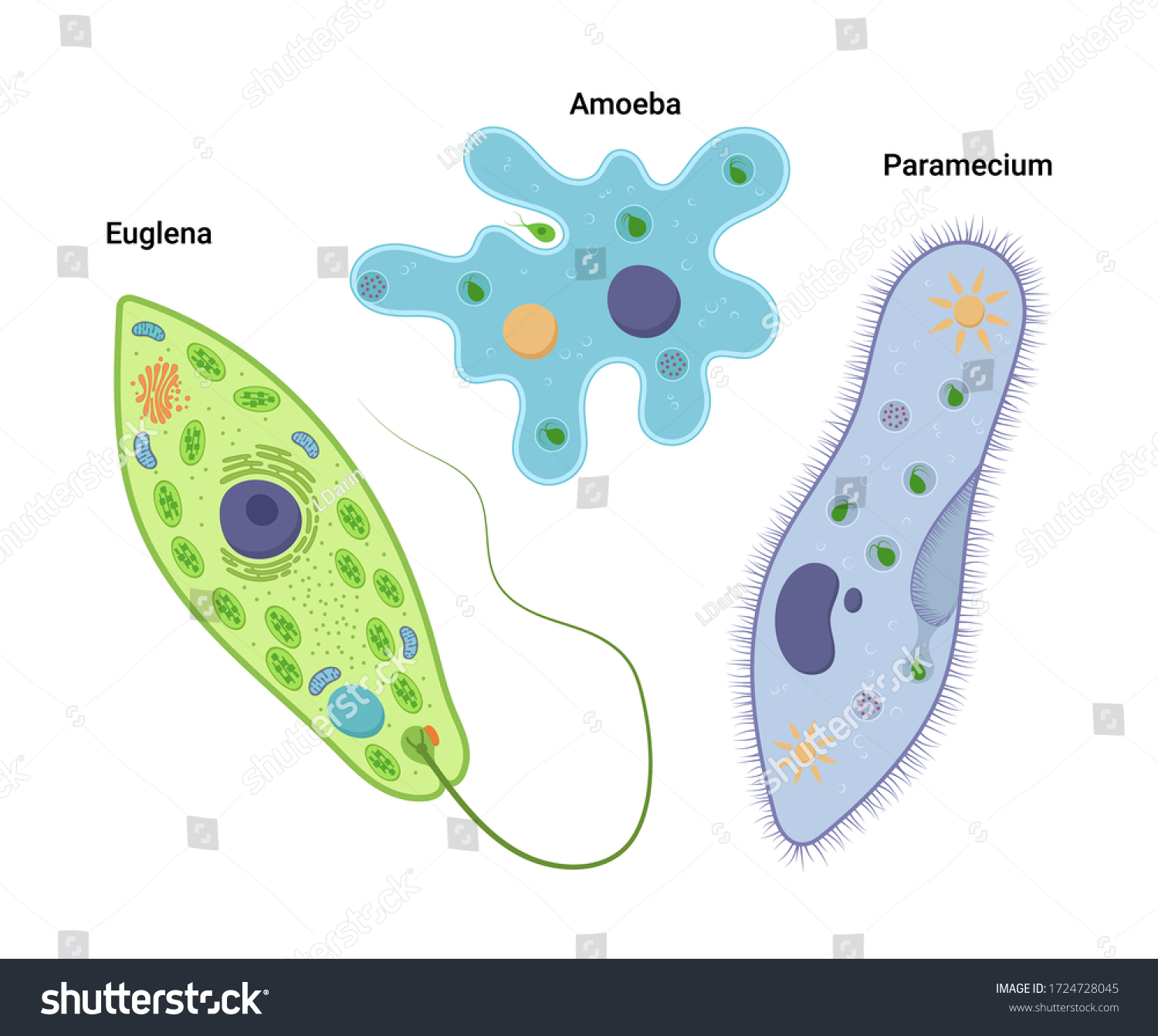

Then you have the Eukaryotic unicellular organisms. These are more "modern," relatively speaking. They have a defined nucleus and little organs called organelles. Think of Amoebas, Paramecia, or even the yeast you use to bake sourdough. They’re more complex, but they still fly solo.

✨ Don't miss: Why Vegan Mac and Cheese with Pumpkin is Actually Better Than the Original

The sheer scale of the invisible world

It’s easy to ignore what you can't see. But if you took all the bacteria on Earth and piled them up, they would outweigh all the animals combined. By a lot.

Dr. William Whitman and his team at the University of Georgia famously estimated there are about $5 \times 10^{30}$ bacteria on Earth. That is a five followed by thirty zeros. You've got more bacterial cells in your gut right now than there are stars in the Milky Way galaxy. If you're looking for the true meaning of unicellular organisms in a global sense, it’s that they are the primary janitors and engineers of our planet.

Without them, the nitrogen cycle stops. Plants die. You die.

They also inhabit places where "complex" life wouldn't stand a chance. We call these extremophiles. There are Archaea living in hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean where the pressure would crush a submarine and the water is hot enough to melt lead. Others live in salt lakes so briny that they’d pickle a human in minutes. They don't just survive; they thrive.

How do they actually work?

Since they don't have mouths or hands, they have to get creative.

Take the Amoeba. It uses something called "pseudopodia," which translates to "false feet." It basically stretches its entire body out, wraps itself around a piece of food—maybe a smaller bacterium—and pulls it inside. This is called phagocytosis. It’s messy, it’s slow, and it’s effective.

Then you have things like Paramecium. These guys are covered in tiny hairs called cilia. They beat these hairs in unison like a thousand tiny oars to swim through water. They even have a specific "oral groove" that acts like a mouth. It’s sophisticated machinery on a microscopic scale.

💡 You might also like: Mormon vs Seventh Day Adventist: What Most People Get Wrong

The big misconceptions about "simple" life

People often call these organisms "simple."

That's a mistake.

Being small doesn't mean you're simple; it means you're efficient. A single bacterium like E. coli can replicate every 20 minutes under ideal conditions. In less than half a day, one cell can become billions. Your body takes nine months just to make one human. Evolutionarily speaking, who’s winning?

Another myth is that all unicellular organisms are "germs."

While it's true that some cause diseases—like Vibrio cholerae (cholera) or Plasmodium (malaria)—most are either harmless or strictly beneficial. You literally cannot digest your dinner without the unicellular help in your large intestine. They break down the fibers your own enzymes can't touch. They synthesize Vitamin K. They even protect you from the "bad" bacteria by hogging all the space and food. It’s a microscopic turf war in your belly, and you want the good guys to win.

The jump from one to many

If being a single cell is so great, why did multicellular life even happen?

It probably started with cooperation. Some unicellular organisms, like Dictyostelium discoideum (social amoebas or "slime molds"), live most of their lives as individuals. But when food gets scarce, they send out a chemical signal. They swarm together. They form a "slug" that can move as a single unit to find a better environment.

Eventually, some cells stopped being temporary partners and became permanent roommates. This is the colonial theory. Over millions of years, cells started specializing. One group focused on movement, another on digestion. This specialization is what eventually led to you. But even in your body, each of your trillions of cells still carries the "memory" of its unicellular ancestors. Your mitochondria—the powerhouses of your cells—were actually independent bacteria billions of years ago that got swallowed by a larger cell and just... stayed. We call this endosymbiosis.

Why you should care about the meaning of unicellular organisms

This isn't just about science lab slides.

👉 See also: Pump Bar in West Hollywood: What Really Happened to the Pink Palace

Understanding these organisms is how we make breakthroughs in medicine and technology. We use yeast (unicellular fungi) to produce insulin for diabetics. We use bacteria to clean up oil spills in the ocean. We are even looking at using them to create "living" building materials that can heal their own cracks.

They are the ultimate recyclers. When a tree falls in the woods, it doesn't just stay there forever. Unicellular fungi and bacteria descend upon it, breaking down the tough lignin and cellulose, returning the carbon to the soil so a new tree can grow. Life is a loop, and the single-celled world is what keeps the loop turning.

What to do with this info

If you're looking to apply this knowledge, start by paying attention to your "internal ecosystem."

- Prioritize your microbiome. Since you're essentially a walking planet for unicellular life, feed the "good" residents. Fermented foods like kimchi, kefir, and sauerkraut are loaded with beneficial Lactobacillus.

- Respect antibiotics. These drugs are designed to kill unicellular pathogens. But they’re like a nuclear bomb in a city—they kill the bad guys and the good guys alike. Never take them for viral infections (they don't work on viruses anyway), and always finish the course to prevent creating "superbugs."

- Get a cheap microscope. Seriously. You can get a decent digital one for under $50. Take a drop of water from a local pond. Looking at the frantic, busy world of a single drop of water will change your perspective on what "alive" really means.

The world is much bigger—and much smaller—than we think. The meaning of unicellular organisms is ultimately that life finds a way to exist in every possible niche. We are just the new kids on the block, living in a world that belonged to the single cell long before we arrived, and will likely belong to it long after we're gone.