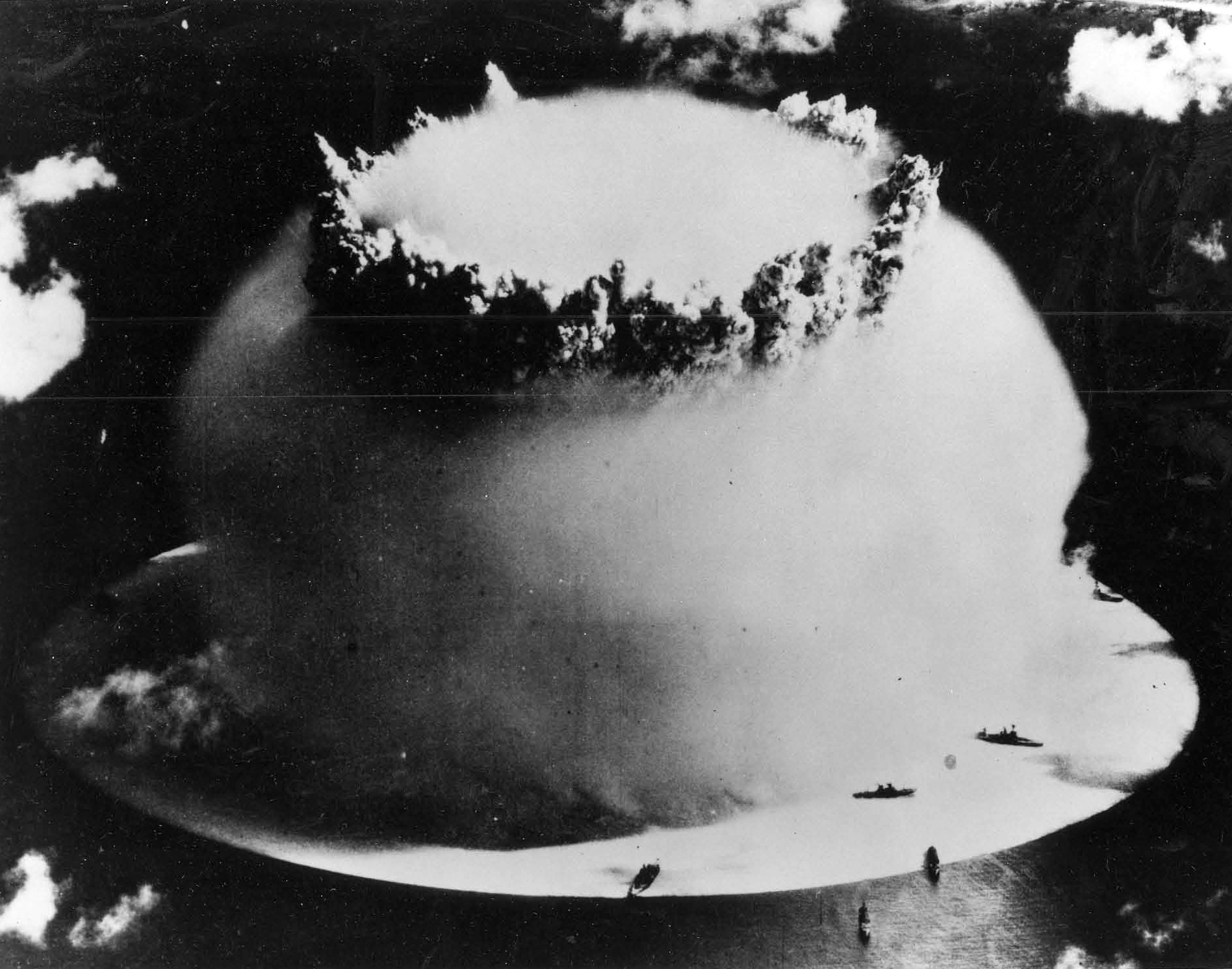

Imagine a pillar of water two miles high. It isn't just water. It’s a radioactive ghost, a 2-million-ton column of spray and pulverized coral rising out of the Pacific like some nightmare cathedral.

In 1946, the world wasn't sure if an underwater atomic bomb explosion would even work. Some physicists thought the pressure of the ocean might just "stifle" the blast. They were wrong. Way wrong.

When the U.S. military detonated "Baker"—the world’s first subsurface nuclear test at Bikini Atoll—the results didn't just sink ships. They changed how we understand the very nature of environmental contamination. Honestly, we are still living with the data from that single, terrifying morning.

The Baker Shot: When the Ocean Became a Weapon

Most people think of nukes as giant mushrooms in the desert. But the underwater atomic bomb explosion at Bikini Atoll was something else entirely. On July 25, 1946, a 21-kiloton plutonium device was suspended 90 feet below the surface of the lagoon.

It went off.

The fireball created a gas bubble that hit the sea floor and the surface almost simultaneously. Within milliseconds, a supersonic shockwave hammered the hulls of the "target fleet"—a collection of captured German and Japanese ships along with aging American vessels.

But it wasn't the blast that was the real problem. It was the "base surge."

📖 Related: Mounting a camera on Hot Wheels cars: How to get that perfect 1:64 scale POV

As the massive column of water collapsed back into the lagoon, it created a mist. A thick, rolling fog of highly radioactive water that coated everything it touched. Unlike an airburst, where most of the radioactive fallout gets sucked up into the stratosphere, an underwater blast keeps the poison right at sea level.

Why the Water Didn't Stop the Radiation

You've probably heard that water is a great shield for radiation. It is. In a controlled pool at a nuclear plant, it's perfect. But in an underwater atomic bomb explosion, the water becomes the delivery mechanism.

The Baker test proved that the water itself becomes intensely contaminated with fission products. We're talking about isotopes like Cesium-137 and Strontium-90. When the spray hit the target ships, it didn't just wash off. It soaked into the wooden decks. It corroded the metal. It became part of the ships' DNA.

The Ships That Wouldn't Die (And Couldn't Be Cleaned)

The Navy tried to scrub the ships. They used lye. They used soap. They even tried sandblasting the hulls. Nothing worked.

The USS Saratoga, a massive aircraft carrier, sank within hours because the hull was basically crushed by the hydraulic shock. But the ships that stayed afloat were arguably worse. They were "hot." They were so radioactive that the sailors couldn't even board them for more than a few minutes without risking lethal doses.

👉 See also: Idle Explained: Why Your Computer is Actually Working When You Aren't

Vice Admiral William P. Blandy, the man in charge of the tests, eventually had to face a hard truth: the fleet was a total loss. Not because of structural damage, but because they were radioactive biohazards. They ended up scuttling most of them in the deep ocean. Just let that sink in.

The Physics of Subsurface Nuclear Blasts

The mechanics of an underwater atomic bomb explosion are fundamentally different from an atmospheric one. In the air, you get a flash of light and a heat pulse. Under the waves, the energy is converted into a massive pressure spike.

Because water is non-compressible, that shockwave travels much further and with more destructive force than it does in the air.

- The Bubble Pulse: The explosion creates a steam bubble that expands and contracts several times, sending out secondary shockwaves.

- The Wilson Cloud: For a split second, the pressure drop behind the shockwave causes moisture in the air to condense, creating a white shroud that hides the initial explosion.

- The Radioactive Rain: Once the column collapses, the "rainout" is 100% toxic.

It’s basically a dirty bomb on a planetary scale.

Misconceptions About Marine Life Recovery

People often point to the fact that Bikini Atoll looks "fine" today as proof that the damage wasn't that bad. That’s a bit of a reach.

While the coral has grown back and sharks are swimming in the lagoon, the terrestrial environment is a different story. The soil still contains high levels of Cesium. If you eat the coconuts grown on the islands, you're ingesting radioactive isotopes.

The underwater atomic bomb explosion didn't just vanish into the currents. It settled into the sediment. Research by scientists like Dr. Ken Buesseler at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution has shown that while the open ocean dilutes radiation, closed lagoon systems act like storage vaults for these isotopes.

The Modern Risk: What Happens Today?

We haven't done an atmospheric or underwater test in decades thanks to the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963. But the data from the 1940s and 50s is still being used to model what would happen in a modern naval conflict.

If a nuclear torpedo were used today, the impact on global shipping and coastal ecosystems would be catastrophic. We aren't just talking about sinking a submarine. We’re talking about rendering entire harbors unusable for generations.

The "Baker" test was a warning that we barely understood at the time. It showed that the ocean isn't just a vast, empty space that can absorb our messes. It’s a conductor. It carries the energy and the poison further than anyone anticipated.

Crucial Lessons from the Deep

If you're looking for the "bottom line" on why these tests matter, it's about the permanence of the mistake.

- Decontamination is a Myth: Once an underwater atomic bomb explosion occurs in a confined area, there is no "cleaning" it. The environment has to be abandoned.

- The Shockwave is the Killer: For naval vessels, the hydraulic hammer of a subsurface blast is far more lethal than the heat of an airburst.

- The Base Surge is the Nightmare: The mist created by these blasts is the most efficient way to spread radiation over a wide area at ground level.

The history of the underwater atomic bomb explosion is a history of hubris. We thought we could control the ocean's reaction to the atom. Instead, we learned that the water would take that energy and turn it into a lasting, toxic legacy that still haunts the Pacific floor.

To truly understand the impact, one should look into the specific deck logs of the USS Skate or the Prinz Eugen. These documents detail the frantic and ultimately futile attempts to "wash away" the invisible fire of the 1940s. The technical reports from Operation Crossroads remain the gold standard for understanding how nuclear weapons interact with our planet's most vital resource.

The next step for anyone interested in this is to study the "Baker" debris field maps. They show exactly where the radioactive sediment settled, proving that even eighty years later, the ocean remembers what we did.