You’ve probably seen it a thousand times in high school textbooks. A simple loop of wire, two magnets with "N" and "S" painted on them, and a battery. It looks easy. But if you actually try to build it based on that generic diagram of a electric motor, you’ll likely end up with a pile of copper that does nothing but get hot.

Electricity is invisible, which makes it weird. We rely on diagrams to visualize what’s happening, but most diagrams prioritize "looking clean" over "working physically."

The heart of the thing is the Lorentz Force. It sounds fancy, but it’s basically just the universe deciding that when an electron moves through a magnetic field, it gets pushed sideways. If you have a wire full of those moving electrons, the whole wire moves. That’s it. That’s the "magic."

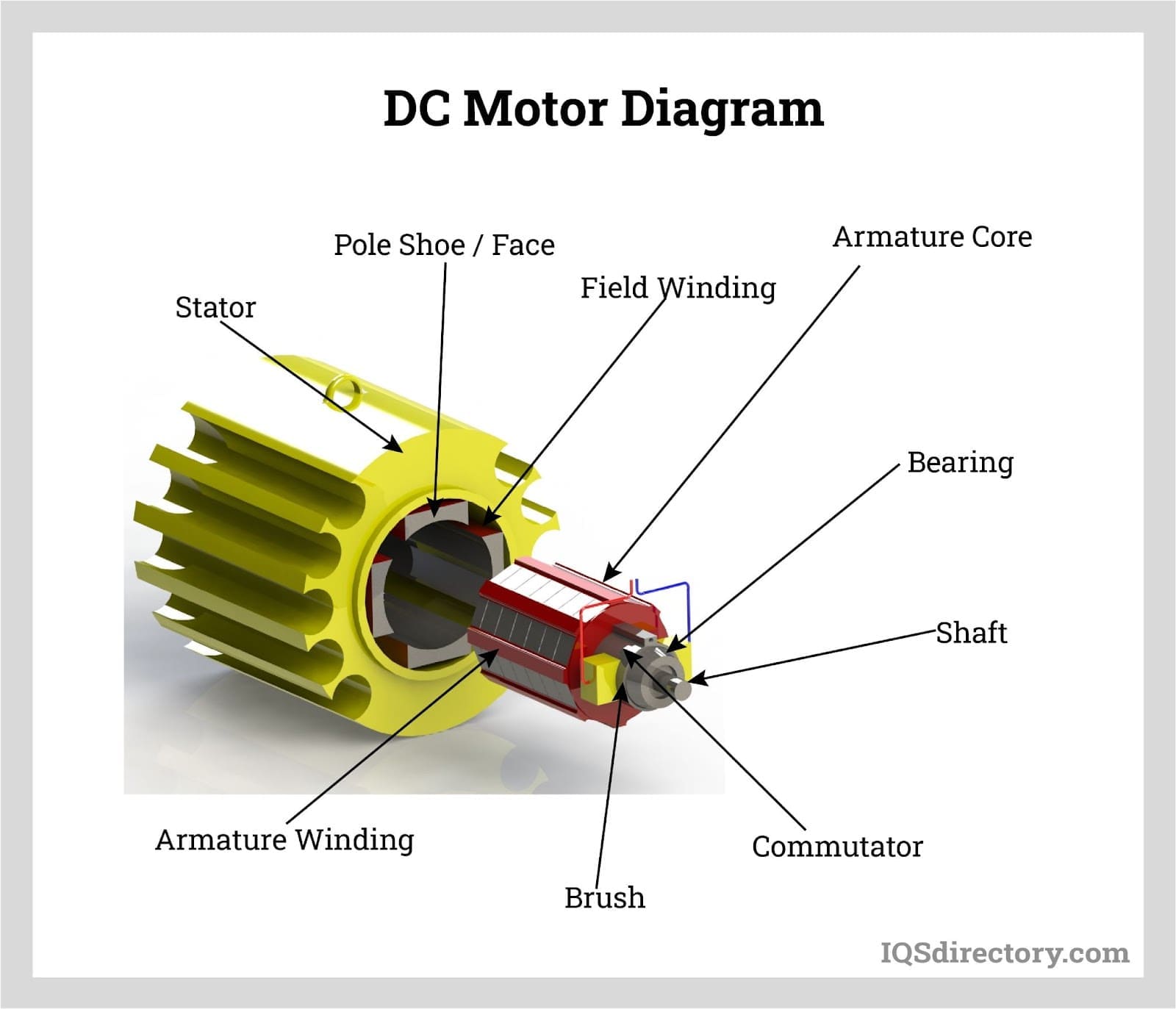

The Anatomy of the Basic Electric Motor Diagram

Let's break down what you're actually looking at when you open a schematic. Every diagram of a electric motor worth its salt has to show the interaction between stationary parts and moving parts.

The Stator: The Part That Stays Put

The stator is the housing. In small toy motors, these are just permanent magnets glued to the inside of a metal can. In the massive motors powering a Tesla or an industrial pump, the stator is a series of complex copper windings.

Why windings? Because we want to control the magnetic field. Permanent magnets are "always on," which is fine for a vibrating phone motor, but not for a machine that needs to vary its torque. By running current through the stator's coils, we create an electromagnet. This gives us the ability to turn the motor's strength up or down just by changing the voltage.

The Rotor (or Armature): The Part That Spins

This is usually the center of your diagram of a electric motor. It’s the shaft and the coils that do the actual rotating. When you see those messy-looking copper bundles in the middle of a motor, that’s the armature.

✨ Don't miss: How Calling You to See Lyrics Actually Works (and When It Doesn't)

The goal here is simple: make the armature's magnetic field fight the stator's magnetic field. They hate each other. They push away. That push creates torque.

The Commutator: The Secret Logic Gate

If you just hooked a battery to a loop of wire between two magnets, the wire would flip half a turn and stop. It would find "equilibrium" and just sit there vibrating.

To keep it spinning, you have to flip the direction of the electricity every half-turn. That’s what the commutator does. It’s a split ring. As it rotates, it physically breaks the connection and swaps the positive and negative leads. It’s mechanical logic. It’s brilliant. Honestly, it's the most underrated invention of the industrial age.

Why Your Diagram Might Be Lying to You

Most people look at a 2D diagram of a electric motor and assume the magnetic field is a straight line. It isn't. Magnetic flux is curvy. It leaks.

If you look at professional engineering schematics from companies like Siemens or ABB, the diagrams look much more "crowded." They account for "air gaps." The air gap is the tiny space between the rotor and the stator. If that gap is too big, the magnetic field weakens exponentially. If it’s too small, the heat expansion will cause the motor to seize and melt.

There's also the "Back EMF" (Electromotive Force) issue. This is something almost no basic diagram shows. As a motor spins, it actually starts acting like a generator. It creates its own electricity that pushes back against the battery. This is why motors draw way more current when they are starting up than when they are running at full speed. If you’ve ever noticed the lights flicker in your house when the AC kicks on, you’ve experienced Back EMF (or the lack thereof during the initial "inrush" current).

The Difference Between AC and DC Diagrams

You can't just swap the power source and expect the same drawing to work.

DC Motor Diagrams usually focus on those brushes and commutators I mentioned. They are "self-switching." You give them juice; they go.

AC Motor Diagrams (specifically Induction Motors) are a whole different beast. There are no brushes. No physical connection to the spinning part. Instead, the stator creates a "rotating magnetic field." Imagine a carrot on a stick. The magnetic field rotates around the circle, and the rotor tries to catch up. It never quite does—this is called "slip." If the rotor actually caught up to the speed of the magnetic field, the physics would break, the induction would stop, and it would slow down again.

Real-World Nuance: The Heat Factor

A perfect diagram of a electric motor looks like it could run forever. In reality, heat is the killer.

✨ Don't miss: AI Regulation News Today October 11 2025: Why Everything Just Changed

In 1821, Michael Faraday showed off the first "homopolar motor." It was just a wire dangling in a pool of mercury. It worked, but it was incredibly inefficient. Modern motors use "laminated cores." If you look closely at a motor's metal parts, they aren't one solid block. They are hundreds of thin slices of steel glued together.

This is to stop "Eddy Currents." Imagine little whirlpools of electricity forming in the solid metal. They don't help the motor spin; they just turn into heat. By slicing the metal into thin layers (laminations), we break those whirlpools. Your diagram might just show a "block," but a real engineer sees a stack of slices.

How to Read a Wiring Schematic Without Getting a Headache

When you look at a wiring diagram of a electric motor in a repair manual, don't look at the whole thing at once. You'll go crazy.

- Find the ground. Always start with where the energy goes to die.

- Locate the capacitor. Most single-phase AC motors (like in your fridge) have a big cylinder on the side. This is the capacitor. It gives the motor a "kick" to start it spinning in one direction. Without it, the motor wouldn't know which way to turn and would just hum until it caught fire.

- Trace the thermal protection. Look for a small symbol (often a little "S" or a zig-zag) that represents the thermal fuse. If your motor isn't working, 90% of the time, this little guy just got too hot and snapped to save the house from burning down.

Actionable Steps for Troubleshooting and Design

If you are trying to use a diagram of a electric motor to fix something or build a prototype, keep these things in mind:

👉 See also: Why Every Cybertruck on Fire Becomes a Viral Obsession

- Check the Brushes First: In DC motors, the brushes are sacrificial. They are made of graphite (pencil lead, basically) and they wear down. If the motor is sparking or intermittent, your brushes are likely worn to nubs. Replace them before you replace the motor.

- Measure Resistance: Use a multimeter to check the coils. If you see "OL" (Open Loop) or 0 ohms, the insulation has melted and the wire is "shorted." The motor is a paperweight at that point.

- The "Spin Test": With the power off, try to spin the shaft by hand. It should be smooth. If it feels "crunchy," your bearings are shot. No diagram can fix a mechanical failure like a seized ball bearing.

- Voltage Drop Matters: If you’re building a DIY project from a diagram, use thicker wire than you think you need. Thin wires have high resistance, which drops the voltage before it even hits the motor, leaving you with no torque.

Understanding the diagram of a electric motor isn't just about knowing where the wires go. It’s about understanding the tug-of-war between magnetism and friction. Next time you hear a vacuum cleaner or an electric car whirring to life, picture that commutator flipping the current thousands of times a minute. It's a violent, beautiful piece of engineering that we've managed to make look boring on paper.

To get started with your own build, find a simplified "brushed DC motor" schematic. Focus on the relationship between the battery voltage and the number of turns in your coil. More turns equals more torque, but less speed. It’s always a trade-off. Choose what your project needs before you start winding.