It’s about the size of a small pear. Most of the time, you don't even think about it until it starts cramping, bleeding, or housing a human being. We’re talking about the uterus. Honestly, it’s one of the most resilient, stretchy, and misunderstood organs in the human body. People often treat it like a passive vessel, but biologically? It’s a muscular powerhouse.

The uterus is the literal center of reproductive health for half the population. It’s located in the pelvic cavity, tucked right between the bladder and the rectum. If you’ve ever wondered why you feel like you have to pee every five minutes during a period or pregnancy, that’s why. It’s a cramped neighborhood down there.

Most people know the basics: it’s where babies grow. But the "womb" (as your grandmother might call it) does so much more. It’s an endocrine-responsive organ that undergoes a massive structural overhaul every single month. It’s essentially a self-renovating room. If no one moves in, it tears down the wallpaper and starts over. That "wallpaper" is the endometrium, and the "tearing down" is your period.

What is the uterus actually made of?

It’s not just a hollow balloon. The uterus is actually composed of three distinct layers that work in total harmony. You’ve got the perimetrium, which is the thin outer slick skin. Then there’s the myometrium. This is the middle layer, and it’s almost entirely smooth muscle. It is incredibly thick. In fact, the myometrium is one of the strongest muscles in the human body by weight. It has to be. It’s the engine that pushes a baby out into the world.

Then you have the endometrium. This is the inner lining. It’s the part that responds to estrogen and progesterone. When those hormones spike, the endometrium gets thick and lush with blood vessels, preparing for an embryo. When they drop, it sheds.

The shape matters too. A typical uterus is "anteverted," meaning it tips forward toward the belly button. However, about 25% of women have a "retroverted" uterus, which tilts backward toward the spine. Usually, this is just a normal anatomical variation, kinda like being left-handed. Doctors used to think it caused infertility, but we now know that’s mostly a myth. It just makes certain pelvic exams a bit more awkward.

👉 See also: Jackson General Hospital of Jackson TN: The Truth About Navigating West Tennessee’s Medical Hub

The four parts you need to know

You can't just look at the uterus as one big blob. It has anatomy.

- The Fundus is the top, rounded part. When a midwife or OB-GYN feels your belly during pregnancy, they are measuring the "fundal height" to see how the baby is growing.

- The Corpus is the body. This is the main event where implantation happens.

- The Isthmus is the narrow neck right at the bottom of the body.

- The Cervix. People often talk about the cervix like it’s a separate organ, but it’s actually the lower part of the uterus. It’s the gatekeeper. It stays tightly shut during pregnancy and opens (dilates) during labor.

Why the "Baby House" label is a bit reductive

While the primary biological "goal" of the uterus is gestation, it’s also a major player in the pelvic floor’s structural integrity. It’s held in place by a complex web of ligaments—the broad ligament, the round ligament, and the uterosacral ligament.

When people have a hysterectomy (the surgical removal of the uterus), it’s not just about losing the ability to carry a child. It can actually shift the dynamics of the pelvic floor. This is why surgeons often try to leave the cervix if possible, or use mesh to ensure the bladder and rectum don't start sagging into the space where the uterus used to live.

It also has a role in sexual response. During orgasm, the uterus actually undergoes rhythmic contractions. Some researchers, like those published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine, have noted that the "uterine orgasm" feels different than a purely clitoral one because of the internal movement and the tugging on those supporting ligaments.

Common glitches in the system

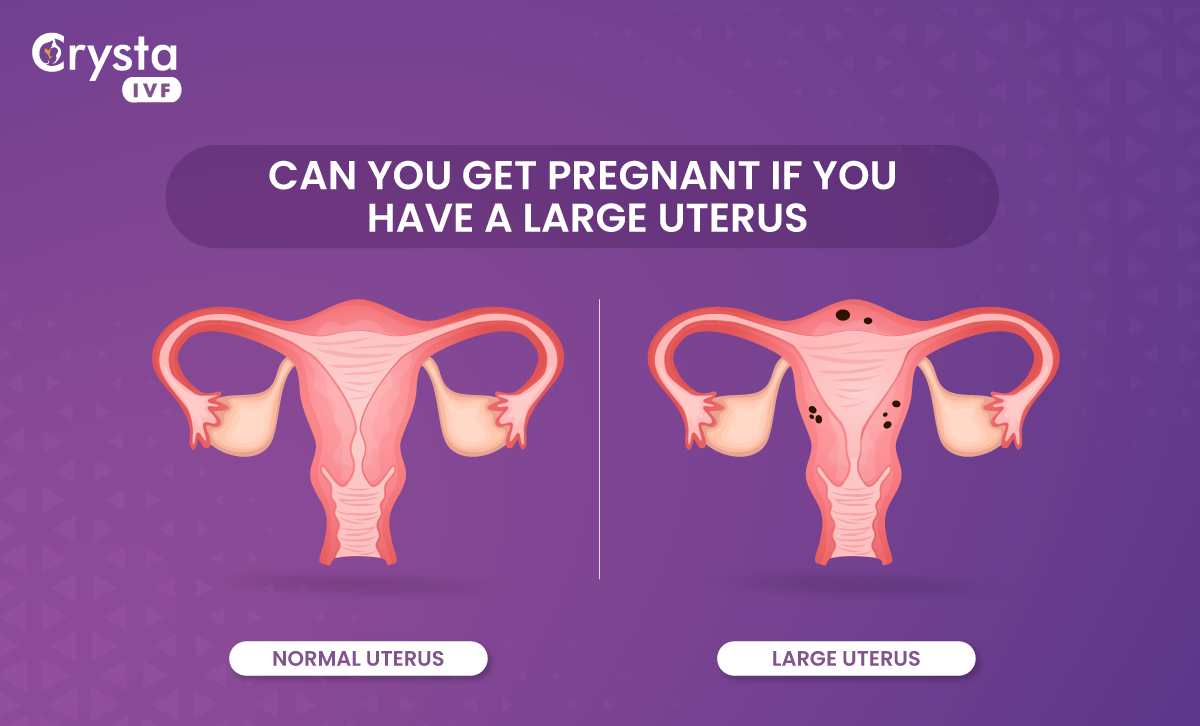

Sometimes the uterus doesn't play nice. Fibroids are a classic example. These are non-cancerous growths in the myometrium. They are incredibly common—some studies suggest up to 80% of women will have them by age 50. Most are tiny and don't do anything. But some can grow to the size of a grapefruit, causing heavy bleeding and "bulk symptoms" where you feel like you’re carrying a heavy brick in your pelvis.

✨ Don't miss: Images of the Mitochondria: Why Most Diagrams are Kinda Wrong

Then there’s Endometriosis. This is when tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus—on the ovaries, the bowels, or the pelvic wall. It’s agonizing. It bleeds every month just like the lining inside the uterus, but since it’s trapped, it causes inflammation and scarring.

And we can't forget Adenomyosis. Think of this as endometriosis's cousin, but instead of the lining growing outside, it grows deep into the muscular wall of the uterus itself. It makes the uterus "boggy" and enlarged. It’s often misdiagnosed as simple "bad cramps," but it’s a distinct structural issue.

The Uterus through the ages

It’s a shapeshifter. Before puberty, it’s tiny. During the reproductive years, it cycles. During pregnancy, it expands from the size of a lemon to the size of a watermelon—a 500-fold increase in volume. That is absolutely wild when you think about it. No other organ can do that and then return (mostly) to its original size.

After menopause, the uterus undergoes "atrophy." Without the constant pulse of estrogen, it shrinks. The lining stays thin. If a person has post-menopausal bleeding, it’s a big red flag for doctors because the uterus should be dormant at that stage.

Taking care of the "Mother Ship"

So, how do you actually look after this thing?

🔗 Read more: How to Hit Rear Delts with Dumbbells: Why Your Back Is Stealing the Gains

First, get your screenings. While the Pap smear actually checks the cervix, it’s your first line of defense for uterine health. Second, pay attention to your "normal." If you are suddenly soaking through a pad every hour or having pain that makes you miss work, that is not "just being a woman." That is a medical symptom.

Diet and lifestyle matter more than people think. Chronic inflammation in the body can exacerbate conditions like fibroids or heavy bleeding. While there's no "magic food" for the uterus, maintaining a healthy weight helps regulate estrogen levels. Since estrogen is what tells the uterine lining to grow, having too much of it (which can happen with higher levels of adipose tissue) can lead to an overthickened lining or increased fibroid growth.

Actionable Steps for Uterine Health

- Track your cycle obsessively. Use an app or a paper journal. Note the heavy days. If you're losing more than 80ml of blood (about 16 soaked pads/tampons) per cycle, talk to a doctor about "Menorrhagia."

- Check your iron. Chronic heavy bleeding from the uterus is the number one cause of anemia in women. If you're exhausted all the time, your uterus might be stealing your red blood cells.

- Advocate for imaging. If you have pelvic pain, a manual exam isn't enough. Ask for a transvaginal ultrasound. It’s the gold standard for seeing what’s actually happening inside the myometrium.

- Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy. If you’ve had a baby or surgery, these therapists are miracle workers. They help retrain the muscles that support the uterus, which can fix everything from "leaking" when you sneeze to painful intercourse.

The uterus is a sophisticated, muscular, hormone-responsive machine. It’s the only organ that can build a whole new life and then go back to its day job a few weeks later. Respect the pear. It’s doing a lot more work than it gets credit for.

Quick Reference: Uterine Health Checklist

- Monitor Bleeding: Anything longer than 7 days or requiring a change of protection every 1-2 hours needs a medical consult.

- Pain Management: Period pain that doesn't respond to NSAIDs (like Ibuprofen) is a signal for further investigation into Endometriosis or Adenomyosis.

- Routine Exams: Annual pelvic exams allow a provider to feel for changes in uterine size or shape that could indicate fibroids.

- Hormonal Balance: Discuss your cycle with an endocrinologist if you experience irregular periods, as this directly affects the health of the uterine lining.