If you ask someone from the coast what they think about when they hear "Oklahoma," they usually describe a giant, flat pancake. They imagine a dusty highway stretching into a horizon that never ends. They’re wrong. Honestly, looking at a topographic map of Oklahoma for the first time is a bit of a shock for people who think the Great Plains are a monolith of boredom.

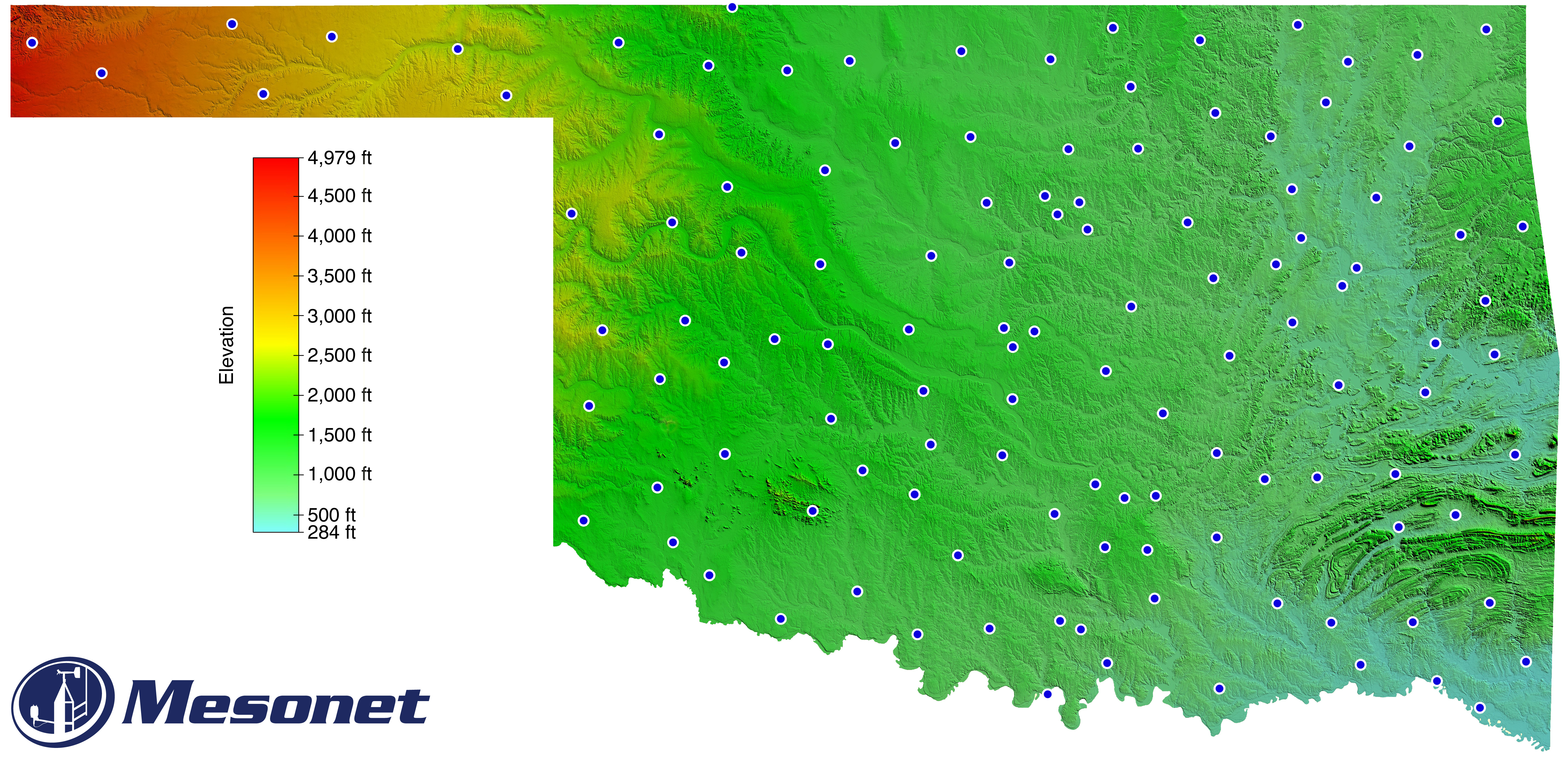

The state actually slants. It’s like a giant tilted floorboards. You start out in the southeast at about 289 feet above sea level near the Little River and by the time you hit the tip of the Panhandle, you’re standing at nearly 5,000 feet. That is a massive change in elevation. It’s not a sudden cliff, but a slow, grinding rise that creates some of the most diverse ecological niches in the central United States.

You’ve got cypress swamps that look like Louisiana in the east and high-altitude shortgrass prairies that feel like New Mexico in the west. This variety isn't just "neat." It dictates where people live, where the water flows, and why certain parts of the state are prone to flash flooding while others are basically deserts.

The Tilted Tabletop: Major Elevation Shifts

The most striking thing about the topographic map of Oklahoma is the northwest-to-southeast drainage pattern. Almost every major river—the Arkansas, the Canadian, the Red—flows in that direction. Gravity is doing the heavy lifting here.

Black Mesa is the king of the map. Tucked into the far corner of Cimarron County, it hits 4,973 feet. If you’ve never been, it’s a basalt-capped plateau formed by ancient volcanic activity. It’s rugged. It’s windy. It feels more like the Rocky Mountain foothills than the Midwest. Contrast that with the Gulf Coastal Plain in the southeastern corner. Down there, the elevation drops so low that you’re dealing with humid, lush wetlands.

Most people live in the middle, in the Cross Timbers region. This is where the hills start to roll. It’s a transition zone. Geologists often point out that Oklahoma is one of the few places where you can see the "Great Plains" actually beginning to buckle and fold into real mountains.

The Mountain Ranges People Forget

Yes, Oklahoma has mountains. Real ones. They aren’t the Himalayas, but they are geologically fascinating and completely change the "flat" narrative.

The Wichita Mountains

Located in the southwest, these are some of the oldest mountains in North America. We’re talking about granite and rhyolite cores that have been eroding for 500 million years. On a topographic map, they look like a sudden, jagged interruption in the surrounding plains. Mount Scott is the famous one, rising about 1,100 feet above the plain. It’s a massive hunk of rock that provides a brutal contrast to the flat wheat fields nearby.

The Ouachita Mountains

Over in the southeast, things get even more dramatic. These aren't just hills; they are part of a folded mountain belt that stretches into Arkansas. The ridges run east-to-west, which is weird because most American mountains run north-to-south. If you’re looking at a relief map, you’ll see long, parallel lines of ridges and valleys. This terrain is so rough that it historically isolated communities, leading to a distinct Appalachian-style culture in the Sooner State.

The Arbuckle Mountains

These are the oldest. They’re basically the weathered stumps of an ancient mountain range. When you drive through the "Big Cut" on I-35, you’re looking at limestone layers that have been tilted almost vertically. It’s a geologist's playground. The topography here is characterized by karst features—caves, sinkholes, and springs. Turner Falls is the centerpiece here, where Honey Creek drops 77 feet over a travertine terrace.

Why the Topography Actually Matters

Topography isn't just about pretty views. It’s about survival and money.

The way the land folds determines the "Dry Line." This is a meteorological boundary where dry air from the high elevations of the west meets moist air from the Gulf of Mexico. Because of the way Oklahoma’s elevation rises toward the Rockies, it creates a literal ramp for air masses. When those masses collide over the varying terrain of central Oklahoma, you get the world’s most intense thunderstorms. The topography is a key ingredient in the recipe for Tornado Alley.

Then there’s the water. Because the state tilts east, all the rainfall from the west tries to squeeze through the river valleys in the east. If you look at the topographic map of Oklahoma, you’ll see why Tulsa and the surrounding Green Country are so much more prone to flooding than Oklahoma City. The water has nowhere else to go.

💡 You might also like: Kelley House Explained: What Really Happened to Edgartown’s Oldest Hotel

Agriculture also follows the contours. The high, flat, semi-arid plains of the Panhandle are perfect for industrial-scale wheat and cattle, provided you can tap the Ogallala Aquifer. Meanwhile, the rugged eastern hills are better for timber and poultry. The land dictates the economy. You don't see many cornfields in the middle of the Ouachita National Forest.

Misconceptions About the "High Plains"

A common mistake is assuming the High Plains (the western third of the state) are perfectly level. They aren't. They are dissected by canyons.

The Gypsum Hills (or Gyp Hills) near Medicine Lodge and Alva are a prime example. The land there is carved into red mesas and deep canyons by water eroding the soft gypsum and shale. On a satellite or topographic view, this looks like a miniature version of the Arizona desert. The bright red soil—caused by high iron oxide content—creates a visual profile that is completely different from the green forests of the east.

Reading the Map: A Practical Breakdown

If you're looking at a USGS (United States Geological Survey) 7.5-minute quadrangle of an Oklahoma area, you need to pay attention to the contour intervals. In the west, those lines are far apart. In the east, they get crowded.

- Green Shading: Usually represents lower elevations, often found in the Red River Valley or the eastern border.

- Brown/Tan Shading: Represents the climbing elevations of the Ozark Plateau in the northeast or the High Plains in the west.

- Purple/Red Lines: Often denote man-made changes, like the massive reservoirs created by the Army Corps of Engineers.

Oklahoma actually has more man-made lakes than almost any other state. These aren't natural. We built them because the topography allowed us to dam up those narrow river valleys to control the chaotic water flow coming off the western "ramp."

Actionable Ways to Use Topographic Data

If you’re planning to buy land, hike, or even just drive through the state, the topography is your best friend. Don't just rely on a standard road map that treats everything as a flat grey surface.

- For Hikers: Use the USGS TopoView tool. You can overlay historical maps with modern ones to see how the terrain has shifted or how man-made lakes like Eufaula have reshaped the valleys.

- For Land Buyers: Always check the "Flood Risk" maps which are derived directly from topographic data. In Oklahoma, a 20-foot difference in elevation is the difference between a dry basement and a total loss during a spring storm.

- For Travelers: If you want the best views, follow the "Scenic Byways" that track along the ridgelines. The Talimena National Scenic Byway follows the crest of Rich Mountain and Winding Stair Mountain. It’s the highest point between the Appalachians and the Rockies if you stay on that specific latitude.

- For Amateur Geologists: Head to the Gloss Mountains. You can actually hike up the mesas and see the stratigraphic layers of the Permian Period exposed in the cliff faces. It’s a vertical history book.

The topographic map of Oklahoma proves that the state is a geographic crossroads. It isn't just one thing. It's a slow-motion collision of swamp, forest, mountain, and prairie. Next time you're driving I-40, watch the horizon. It isn't flat; it's a long, steady climb into the sky.