You’ve probably watched a rusty old nail sitting in a puddle for weeks. It barely changes. Then, you've seen a firework explode in a fraction of a second. Why the difference? It comes down to one fundamental concept: what is the rate of the reaction and how do we actually measure the pace of change at a molecular level?

Chemistry isn't just about what happens. It's about how fast it happens.

If you're brewing beer, you want that fermentation to hit a sweet spot—not too slow that it spoils, not so fast that it tastes like jet fuel. In a car engine, the combustion needs to be near-instantaneous. Honestly, the rate of the reaction is the heartbeat of every chemical process on Earth. It is defined as the change in concentration of a reactant or a product per unit of time. Think of it like a speedometer for molecules.

The Collision Theory: It’s All About the Impact

Molecules are messy. They don’t just magically turn into something else because they’re near each other. For a reaction to occur, particles have to physically slam into one another. But not just any bump will do.

Max Trautz and William Lewis developed the Collision Theory over a century ago, and it still holds up as the gold standard for understanding reaction speeds. For a "successful" collision, two things must happen. First, the particles need enough "oomph"—what we call activation energy ($E_a$). Second, they have to hit each other at the right angle. If they graze each other like passing cars, nothing happens. They stay exactly as they were.

Imagine trying to snap two LEGO bricks together while throwing them across a room. Most of the time, they’ll just bounce off. You need the right speed and the right orientation to get them to click. That’s chemistry in a nutshell.

💡 You might also like: Lake House Computer Password: Why Your Vacation Rental Security is Probably Broken

What Actually Changes the Rate of the Reaction?

You can't just tell molecules to hurry up. You have to change the environment. Several factors dictate whether a reaction crawls or sprints.

Concentration and Pressure

If you’re in a crowded subway station, you’re more likely to bump into someone than if you’re in an empty field. That’s concentration. In liquids or gases, increasing the concentration of reactants means more particles are crammed into the same space. More particles mean more collisions. Simple. For gases, we usually talk about pressure. Squish the gas into a smaller volume, and you’ve basically dialed up the collision frequency.

Temperature: The Kinetic Kick

This is the big one. When you heat things up, particles move faster. Kinetic energy increases. But it’s not just about moving more; it’s about hitting harder. A higher percentage of those collisions will now have enough energy to clear the activation energy hurdle. Svante Arrhenius actually gave us a math formula for this—the Arrhenius equation—which shows how the rate constant $k$ grows exponentially with temperature.

Surface Area

Ever tried to light a massive log with a match? It’s frustrating. But use wood shavings, and it catches instantly. By breaking a solid into smaller pieces, you expose more "surface" for the other reactants to attack. This is why grain elevators sometimes explode; the dust in the air has so much surface area that a single spark causes a reaction rate that is terrifyingly fast.

Catalysts: The Secret Shortcuts

Catalysts are the cheaters of chemistry, but in a good way. They speed up the rate of the reaction without being consumed themselves. They provide an alternative pathway—sort of a molecular "backdoor"—that requires less activation energy. Your body is full of them; we call them enzymes. Without carbonic anhydrase, you wouldn't be able to process $CO_2$ out of your blood fast enough to stay alive. You’d literally suffocate while breathing.

📖 Related: How to Access Hotspot on iPhone: What Most People Get Wrong

Measuring the Pace: Rate Laws and Constants

We don't just guess at speeds. We use the Rate Law. Generally, it looks something like this:

$$Rate = k[A]^m[B]^n$$

In this equation, $k$ is the rate constant, and the brackets $[A]$ represent the concentration of the reactants. The little exponents ($m$ and $n$) are the reaction orders. You can't find these by looking at a balanced equation. You have to get in the lab and actually measure them.

Sometimes, doubling a reactant doubles the rate (first order). Other times, doubling it quadruples the rate (second order). And occasionally, you can add as much as you want and the rate doesn't budge at all (zero order). Chemistry is weird like that.

The Reality of Reaction Mechanisms

Most reactions don't happen in one big "poof." They happen in steps. We call this the reaction mechanism.

👉 See also: Who is my ISP? How to find out and why you actually need to know

Think of it like a relay race. Each step has its own speed. But here's the kicker: the overall rate of the reaction is determined by the slowest step. Scientists call this the Rate-Determining Step (RDS). If you’re building a car and the engine takes three days to assemble but the tires take ten minutes, you’re only making one car every three days. The tires don't matter. To speed up the whole process, you have to fix the slow part.

In the reaction between nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide:

- $NO_2 + NO_2 \rightarrow NO_3 + NO$ (Slow)

- $NO_3 + CO \rightarrow NO_2 + CO_2$ (Fast)

Because the first step is the bottleneck, the concentration of $CO$ actually doesn't affect the initial rate at all. It’s counterintuitive, but that’s why experimental data is so much more important than what’s written on paper.

Real-World Stakes: Why This Matters

This isn't just for textbooks. Controlling the rate of the reaction saves lives and billions of dollars.

- Food Preservation: We use refrigerators to lower the temperature. This slows down the rate of the biochemical reactions that bacteria use to spoil your milk.

- Automotive Safety: Airbags rely on the decomposition of sodium azide ($NaN_3$). This reaction has to happen in about 30 milliseconds. If it was slower, your head would hit the dashboard before the bag inflated.

- Pharmaceuticals: Time-release medication is engineered to have a specific reaction rate in the stomach. If the rate is too high, you get a toxic "dose dump." If it's too slow, the medicine never reaches a therapeutic level in your bloodstream.

Practical Insights for the Lab or Field

If you're looking to manipulate or calculate reaction rates, keep these pointers in mind:

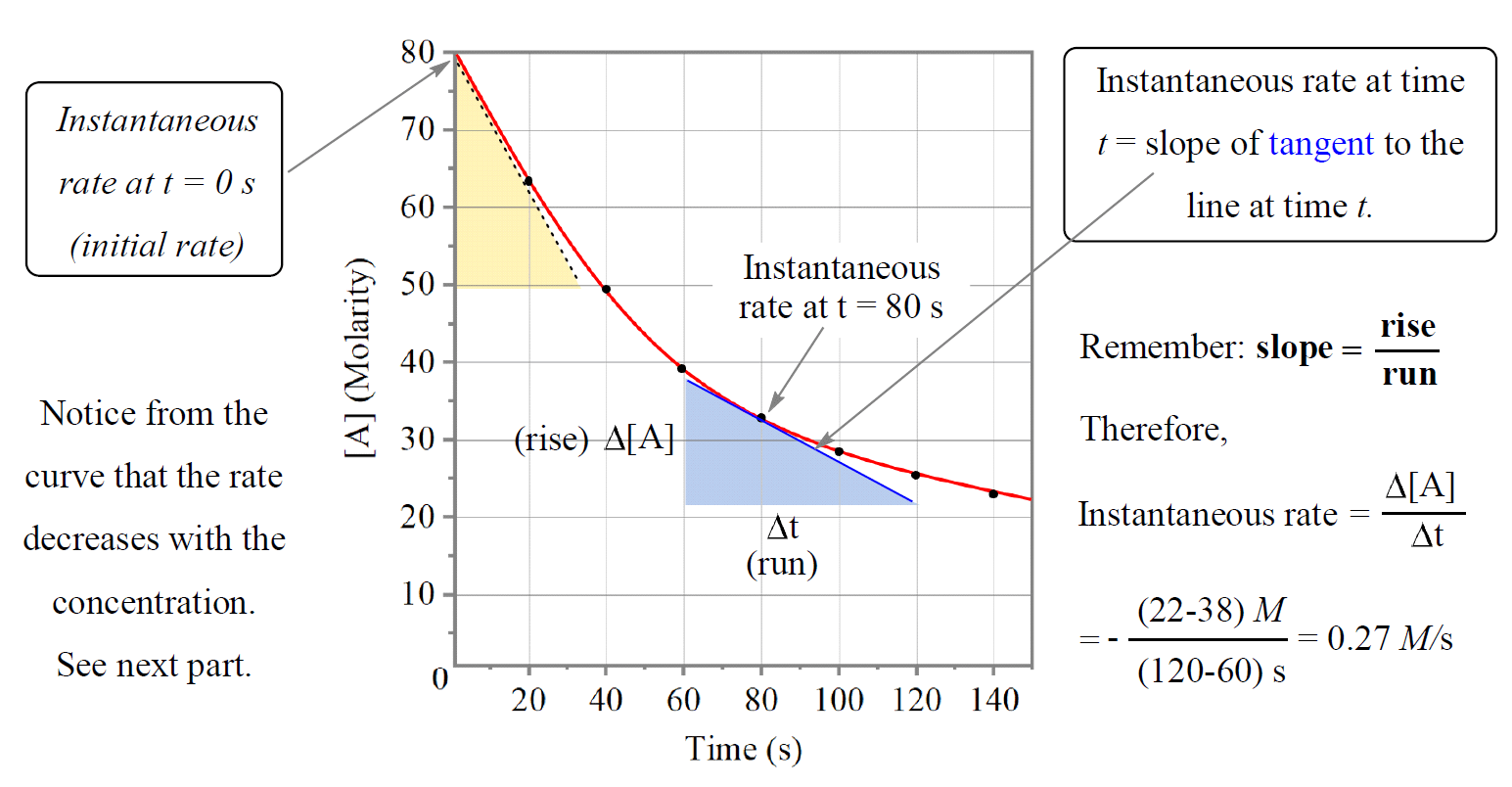

- Stopwatch at the Ready: Always measure the disappearance of reactants or the appearance of products over a specific window ($t_1$ to $t_2$). Initial rates are usually the most accurate because "back-reactions" haven't started yet.

- Watch the Units: The units for the rate constant $k$ change depending on the overall order of the reaction. For a first-order reaction, it's $s^{-1}$. For second-order, it’s $M^{-1}s^{-1}$. Forgetting this is the easiest way to fail a lab report.

- Monitor the Environment: Even a 2°C fluctuation in room temperature can significantly skew your data. Use a water bath if you need precision.

- Check for Inhibitors: Sometimes, things you didn't mean to put in the beaker (like impurities on glassware) can act as "negative catalysts" or inhibitors, slowing everything down.

Understanding the rate of the reaction is about gaining control over the physical world. It's the difference between a controlled burn and an explosion, or a life-saving drug and a useless pill. By mastering the variables—temperature, concentration, and catalysts—you aren't just observing chemistry; you're directing it.