If you’ve ever stood near a massive power plant and felt that low-frequency hum vibrating in your chest, you’ve experienced the Rankine cycle in action. It’s the workhorse of the world. Coal, nuclear, concentrated solar—they all pretty much rely on this same thermodynamic loop to keep the lights on. But if you really want to see what’s happening inside those miles of steel piping, you have to look at a Rankine cycle T-s diagram.

It’s just a graph. Or at least, that’s what it looks like at first glance. Temperature on the vertical axis, entropy on the horizontal. But honestly? This diagram is more like a medical chart for a steam turbine. It tells you exactly where the system is wasting energy, where it’s working efficiently, and where the metal is screaming under the pressure.

Most people get tripped up by the "bell curve" in the middle—the vapor dome. That’s where the magic, and the headaches, happen.

The Four Stages You Actually Need to Know

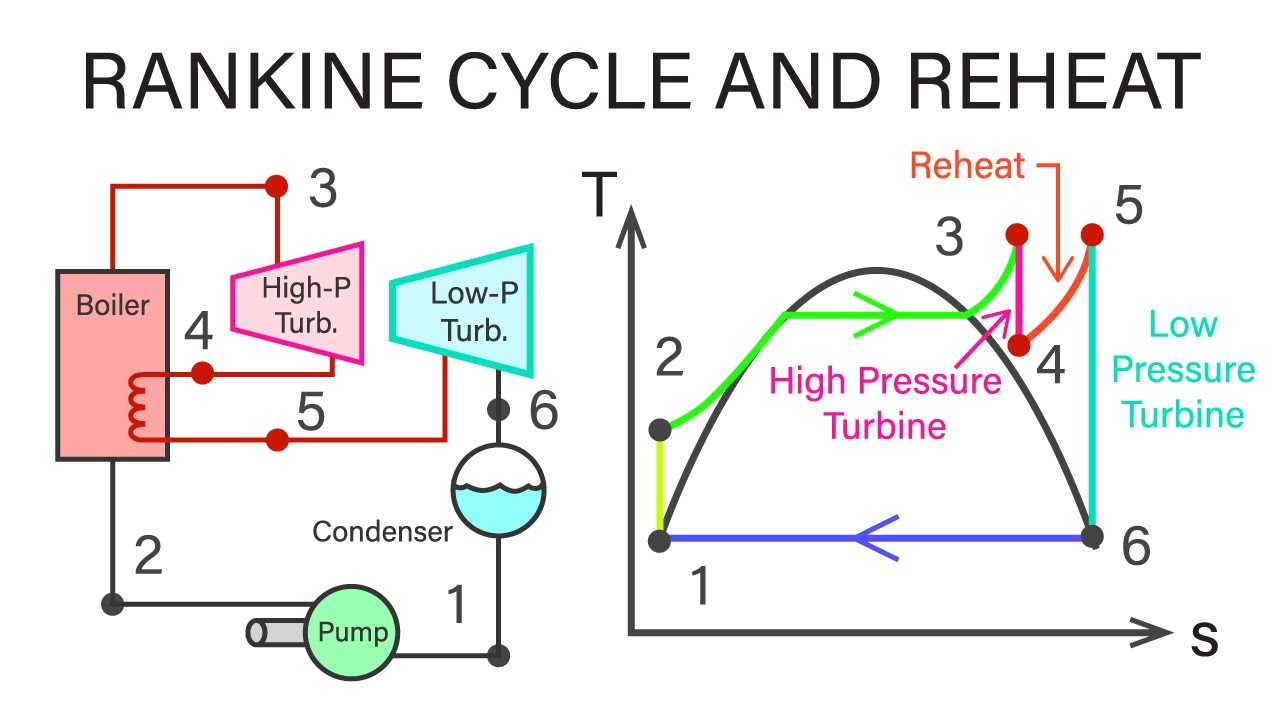

The ideal Rankine cycle is a closed loop. Water goes in, gets hammered by heat, spins a turbine, gets cooled back down, and does it all over again. On a Rankine cycle T-s diagram, this looks like a lopsided rectangle hugging the right side of the saturation curve.

First, you have the pump. This is process 1-2. It’s a short, vertical jump. In a perfect world, this is "isentropic," meaning entropy doesn't change. You’re just squeezing liquid water to a high pressure. Because water is basically incompressible, the temperature barely moves. It’s a boring part of the graph, but without it, the rest of the cycle fails.

Then comes the boiler (2-3). This is where things get interesting. The line moves right, climbing up the side of the liquid region until it hits the saturation curve. Then it goes dead flat. Why? Because the temperature doesn't rise while water is boiling; all that energy is going into breaking molecular bonds. This flat line is the "latent heat" phase. If you’re looking at a modern plant, that line continues past the dome into the "superheat" region. Engineers love superheated steam. It’s dry. It’s fast. And most importantly, it won't erode your turbine blades like a sandblaster.

✨ Don't miss: iPhone 16 Pro Natural Titanium: What the Reviewers Missed About This Finish

Next is the turbine (3-4). This is the money-maker. The line drops vertically (ideally) as the steam expands and does work. On the Rankine cycle T-s diagram, you’re looking for a long drop. The further it drops, the more power you’re extracting. If the line tilts to the right, you’re losing efficiency to friction and turbulence. We call that "entropy generation," and in the power industry, it's essentially burning money.

Finally, the condenser (4-1). The steam, now a exhausted mixture of mist and vapor, gets turned back into pure liquid. The line moves left, back to the start.

Why the Shape of the Curve Matters for Real Engineering

You can’t just draw a perfect rectangle and call it a day. Real life is messy.

Take the "moisture problem" at state 4. If your turbine expansion ends too far to the left—inside that vapor dome—you’ve got water droplets forming. Imagine a turbine blade spinning at 3,600 RPM. Now imagine it hitting a microscopic bead of water. At those speeds, that water bead acts like a bullet. It pits the metal. It causes "cavitation-like" erosion.

This is why the Rankine cycle T-s diagram for a real plant like the Beulah, North Dakota gasification plant or a standard Westinghouse nuclear design always shows "Superheating." By pushing the top-right corner of the diagram further to the right, engineers ensure the steam stays "dry" as it exits the turbine.

🔗 Read more: Heavy Aircraft Integrated Avionics: Why the Cockpit is Becoming a Giant Smartphone

The Reheat and Regenerative Tweaks

If you look at the T-s diagram for a high-efficiency supercritical plant, it looks like a zig-zag. This is "Reheating." They take the steam out of the turbine halfway through, send it back to the boiler to get hot again, and then shove it back into a low-pressure turbine.

- It increases the average temperature at which heat is added.

- It keeps the "exhaust" steam dry.

- It boosts thermal efficiency by a few crucial percentage points.

Then there’s regeneration. This is basically the "recycling" of the power world. Engineers bleed off a little bit of hot steam from the turbine to pre-heat the cold water coming from the pump. On the Rankine cycle T-s diagram, this manifests as a more efficient climb toward the boiling point. It narrows the gap between the heat source and the working fluid.

Real-World Limitations and the Entropy Tax

Entropy is the tax man of the universe. In a textbook, the pump and turbine lines are perfectly vertical (isentropic). In a real plant? Never.

The line for the turbine always leans to the right ($s_2 > s_1$). This is because of internal friction and heat leaks. The ratio of the actual work produced to that "perfect" vertical line is what we call the isentropic efficiency. If a plant manager sees that line leaning further and further right over months of operation, they know their turbine seals are failing or the blades are fouled.

Honestly, the Rankine cycle T-s diagram is the most honest tool we have. It doesn't care about your marketing brochures or "green" claims. It shows exactly how much energy is being dumped into the river or cooling tower. In a typical coal plant, about $60%$ of the energy is lost as waste heat. You can see it right there—the huge area under the 4-1 line. It’s humbling, really.

💡 You might also like: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

How to Read a T-s Diagram Like a Pro

If you're looking at one of these for an exam or a job interview, don't just stare at the lines. Look at the areas.

The area under the heat-addition line (2-3) represents the total heat put into the system ($Q_{in}$). The area under the cooling line (4-1) is the heat rejected to the environment ($Q_{out}$). The area inside the loop? That’s your net work.

$$W_{net} = Q_{in} - Q_{out}$$

If you want a more efficient plant, you want to make that "inside" area as fat as possible while keeping the "underneath" area as small as possible. You do that by raising the boiler pressure (lifting the top of the rectangle) or lowering the condenser pressure (dropping the floor of the rectangle).

Practical Next Steps for Analyzing Cycle Performance

If you're tasked with optimizing or understanding a power system, don't just look at the numbers in a spreadsheet. Plot them.

- Identify your state points. Get the pressure and temperature at the turbine inlet, turbine outlet, pump inlet, and boiler inlet.

- Consult the Steam Tables. Use these to find the Entropy ($s$) and Enthalpy ($h$) for each point.

- Sketch the T-s diagram manually. Even a rough sketch will tell you if your data is wrong. If your turbine expansion line is moving to the left, you've broken the second law of thermodynamics (or, more likely, you misread the table).

- Calculate the Isentropic Efficiency. Compare your real-world "leaning" line to the theoretical vertical line. Anything below $85%$ for a large turbine usually indicates a mechanical issue.

- Look for the "Pinch Point." In the heat exchanger (boiler), ensure there's enough temperature difference between the flue gas and the water. If the lines on your diagram get too close, heat transfer slows down to a crawl, and you'll need a massive, expensive boiler to compensate.

The Rankine cycle T-s diagram remains the gold standard for visualizing these trade-offs. Whether we're moving toward small modular reactors (SMRs) or advanced geothermal, the T-s diagram will be the map we use to navigate the transition.