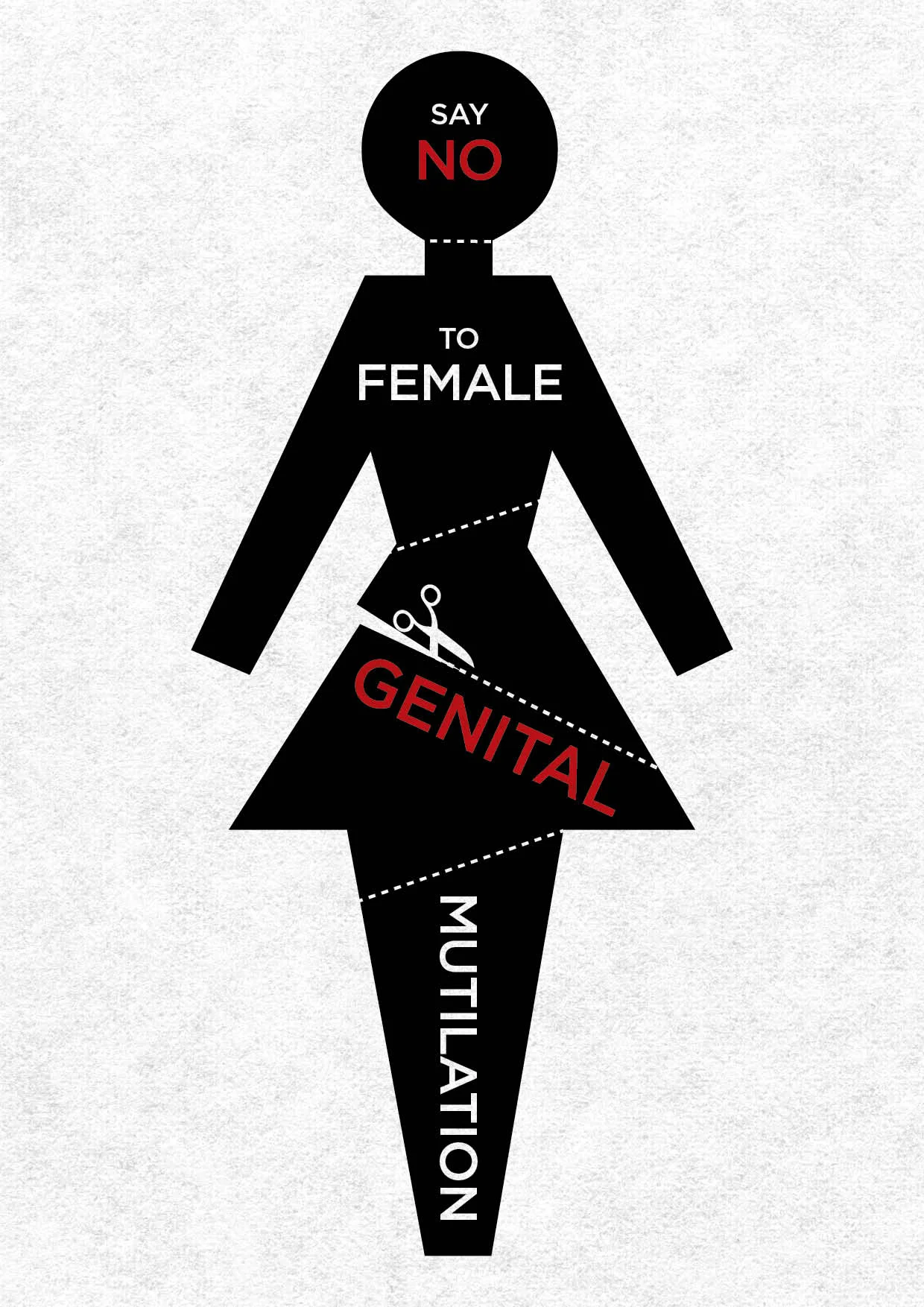

It is a difficult subject. Most people flinch when the topic comes up, and honestly, that’s a pretty natural reaction. When we talk about Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), or female circumcision as some communities call it, the conversation usually shifts immediately to the "how" or the "where." But the "why" is actually the most complex part of the whole puzzle. If we want to understand the purpose of FGM, we have to look past the surface level and dig into the deep-seated social mechanics that keep this practice alive in over 30 countries across Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

It’s not just one thing. There isn't a single manual that people follow. Instead, it’s a messy mix of cultural identity, control, and some really persistent myths about the human body.

The Social Pressure Cooker

Basically, the primary purpose of FGM in most societies where it’s practiced is social acceptance. Imagine living in a village where every woman you know—your mother, your grandmother, your best friend—has undergone this procedure. In these spots, FGM isn't seen as "mutilation." It’s seen as a rite of passage. It’s the ticket to belonging.

If a girl doesn't go through with it, she risks being an outcast. She might be labeled "unclean" or "childish." In many cultures, like certain groups in Ethiopia or Somalia, a woman who hasn't been cut is considered unmarriageable. When marriage is the only path to economic security, you can see why parents—even those who love their daughters deeply—feel forced to continue the cycle. They aren't trying to be cruel. They’re trying to ensure their daughter has a future. It’s a survival strategy.

The Virginity and Fidelity Myth

One of the most persistent reasons cited for the purpose of FGM is the control of female sexuality. There’s this widespread, scientifically incorrect belief that removing the clitoris or the labia will reduce a woman's libido. The idea is to "protect" her virginity before marriage and ensure her "fidelity" afterward.

It’s about control. Plain and simple. By physically altering the body to make sex less pleasurable or even painful, the community attempts to regulate a woman’s sexual behavior. You'll often hear elders talk about "calming" a girl down. From a medical standpoint, we know this is a fallacy. Sexuality isn't a light switch located in a single piece of tissue; it's a complex interaction of hormones, psychology, and the nervous system. But the myth persists because it serves a patriarchal structure.

✨ Don't miss: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

Religious Misconceptions

Here is where things get really confusing for a lot of people. Many practitioners believe that the purpose of FGM is a religious requirement. You’ll find it in some Muslim communities, some Christian communities, and even among some practitioners of traditional African religions.

But here is the kicker: no major religious text actually mandates it.

- The Quran does not mention FGM.

- The Bible doesn't mention it.

- The Torah doesn't mention it.

Scholars from the Al-Azhar University in Cairo—one of the most respected seats of learning in the Islamic world—have issued fatwas (legal rulings) stating that FGM is not an Islamic requirement and is, in fact, harmful. Yet, at the local level, a village imam or priest might still preach that it’s "Sunnah" or "clean." This gap between high-level theology and local tradition is where the practice hides. It gets wrapped in the cloak of holiness to make it harder to challenge.

Hygiene and Aesthetics

You’ll often hear the word "unclean" used to describe uncut women. In some cultures, the purpose of FGM is framed as a matter of hygiene. There is a bizarre belief that the external female genitalia are "male parts" that need to be removed to make a woman truly feminine.

Some myths even claim that if the clitoris isn't removed, it will grow to the size of a penis, or that it will kill a baby during childbirth if it touches the baby's head. To be clear: none of this is true. It’s biologically impossible. But if you’ve been told this since you were five years old by everyone you trust, you’re going to believe it. It becomes an "aesthetic" standard. Just like some cultures value certain tattoos or piercings, these communities have been conditioned to see a "closed" or "smooth" genital area as the peak of beauty and cleanliness.

🔗 Read more: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

The Medical Reality vs. The Perceived Purpose

While the perceived purpose of FGM is "protection" or "purity," the medical reality is the exact opposite. Because these procedures are often done with unsterilized tools—razor blades, glass, or knives—and without anesthesia, the immediate risks are terrifying. We’re talking about severe bleeding (hemorrhage), infections, and shock.

Long-term? It’s a disaster for the body.

- Chronic pain.

- Recurrent urinary tract infections because the flow of urine is obstructed.

- Painful menstruation because the blood can't escape easily.

- Massive complications during childbirth, including obstetric fistula.

When you look at the "purpose" versus the "outcome," there is a massive disconnect. The community thinks they are preparing a woman for motherhood, but they are often making motherhood much more dangerous for her.

Why Does It Continue?

You might wonder why, with all the global outcry and the laws being passed, this hasn't stopped. It’s because FGM is "self-enforcing." If you are the only mother in your village who refuses to cut her daughter, your daughter might never find a husband. She might be teased. She might be barred from communal ceremonies.

It takes a "critical mass" of people to stop all at once. This is what organizations like Tostan have found in West Africa. You can’t just tell one family to stop; you have to get the whole village to agree to a collective abandonment. When the whole village says "We won't do this anymore," the social pressure vanishes. The purpose of FGM—which was social inclusion—suddenly disappears because the "rules" of the club have changed.

💡 You might also like: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

Nuance in the Practice

We also have to acknowledge the trend toward "medicalization." In countries like Egypt or Malaysia, parents are increasingly taking their daughters to doctors or nurses to have the procedure done. They think this solves the problem because it's "safer" and "cleaner."

This is a trap. Medicalization doesn't change the fact that it's a violation of human rights and has no health benefits. It just gives the practice a veneer of legitimacy. Even if a doctor does it in a sterile clinic, the psychological trauma and the fundamental goal of controlling a woman's body remain exactly the same.

Actionable Steps for Understanding and Advocacy

If you're looking to help or just want to be better informed, don't just look at this as a "barbaric" tradition from far away. It happens in the US, the UK, and Europe within immigrant communities. Understanding the purpose of FGM is the first step toward dismantling it.

- Support Grassroots Organizations: Look for groups like the Orchid Project or Desert Flower Foundation. They don't just lecture; they work with community leaders to change minds from the inside out.

- Educate Without Shaming: Shaming a community often makes them retreat and hold onto their traditions tighter. The most effective change comes from "community-led" education where locals talk to locals.

- Understand the Law: Familiarize yourself with the laws in your own country. Many places have "vacation cutting" laws that make it illegal to take a child abroad for FGM.

- Listen to Survivors: Experts like Jaha Dukureh or Leyla Hussein have shared their stories not just to shock, but to explain the social pressure they faced. Their insights are more valuable than any textbook.

The purpose of FGM is deeply rooted in the human desire to belong and the societal urge to control. Breaking that link requires more than just a law; it requires a shift in what it means to be a "good woman" in these communities. By replacing FGM with alternative rites of passage that celebrate girls without harming them, we can preserve culture while protecting health.

Key Resources for Further Reading

- World Health Organization (WHO): Fact sheets on the health consequences of FGM.

- UNICEF: Data and statistics on prevalence rates by country.

- The Girl Generation: Resources on how to talk about FGM in a culturally sensitive way.

Ending FGM isn't about attacking a culture; it's about empowering that culture to protect its most vulnerable members. It's about realizing that "tradition" is a living thing that can, and should, evolve when it no longer serves the well-being of the people.