Ever spent an afternoon staring at a computer screen, dragging a little red pin over your hometown, and hitting "detonate"? It’s a macabre curiosity. We’ve all done it. Whether you're using Alex Wellerstein’s famous NUKEMAP or the MISSILEMAP, looking at a nuclear bomb map radius is a sobering, weirdly addictive experience. But honestly, most people misinterpret what those colorful circles actually mean. They see a ring and think, "Okay, if I'm outside that line, I'm fine."

Reality is much messier.

Thermal radiation, pressure waves, and ionizing radiation don't respect neat little lines on a Google Map. When you look at a nuclear bomb map radius, you’re looking at mathematical averages based on Cold War data, mostly derived from atmospheric tests in the Nevada desert or the Marshall Islands. It’s technology used to visualize the unthinkable. But a map is just a 2D representation of a 4D nightmare.

Why Geography Breaks the Map

A digital map assumes the world is flat and empty. It isn't. If you drop a 100-kiloton warhead—about the size of a standard W76 warhead found on a Trident II missile—over a city like San Francisco, the "perfect circles" on your screen are going to lie to you.

Hills matter. Buildings matter. Even the humidity in the air on a Tuesday afternoon changes how far that thermal pulse travels. In a dense urban environment, the "canyon effect" of skyscrapers can funnel a blast wave, making it more lethal in one direction while providing a weird sort of "shadow" protection in another. If you're behind a massive concrete structure or a significant ridge, your personal nuclear bomb map radius looks very different from your neighbor's.

The Layers of the Blast

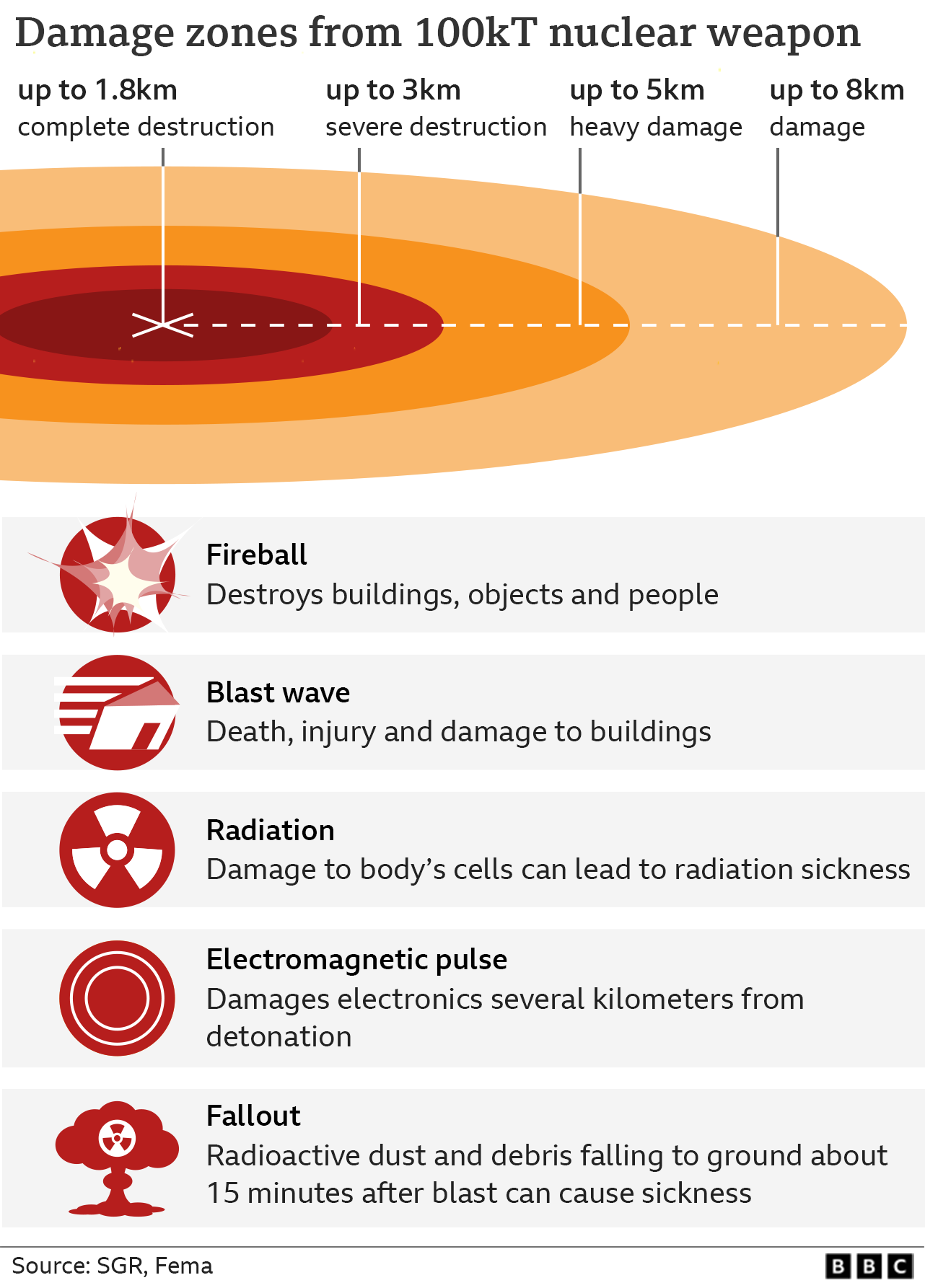

Most simulators break the destruction down into four or five main categories. You’ve got the fireball, the radiation ring, the air blast, and the heat.

The fireball is the simplest part. It’s basically the sun coming to visit. Anything inside this radius is vaporized. Gone. Converted into plasma. For a 15-kiloton "Little Boy" style bomb, this is relatively small—maybe a few hundred yards. But move up to a 5-megaton monster like the Chinese DF-5, and that fireball stretches over a mile.

Then comes the radiation.

This is the part that creeps people out the most. The "Initial Ionizing Radiation" ring usually covers an area where, if you aren't killed by the blast or heat, you'll likely receive a dose of 500 rems. That's a death sentence. About 90% of people in this zone die within a few weeks. It’s a quiet, invisible killer that ignores walls but is stopped by thick lead or several feet of dirt.

💡 You might also like: Current Weather Radar St. Louis Missouri: What Most People Get Wrong

The Deceptive "Light Damage" Zone

When playing with a nuclear bomb map radius tool, you’ll notice a massive outer ring. Usually, it’s labeled "Light Blast Damage." This sounds almost... gentle? Like a bad storm?

It's not.

In this zone, the glass breaks. That sounds minor until you realize that a city is made of glass. Thousands of pounds of jagged shards flying at 100 miles per hour transform an office building into a giant blender. Most injuries in the outer rings of a nuclear detonation aren't from radiation or heat; they're from falling masonry and flying glass. If you're looking at a map and you're in the "light damage" zone, you aren't "safe." You’re just not vaporized.

Thermal Radiation and the 3rd-Degree Burn

Heat travels faster than the blast wave. It’s the first thing that happens after the flash. If you’re within the thermal radiation radius, the air itself catches fire. We're talking about a pulse of light so intense it can ignite clothing and upholstery miles away.

For a 1-megaton blast, you could get third-degree burns up to 5 miles away. Think about that. You’re standing in your kitchen, five miles from the "center," and suddenly the side of your body facing the window is charred. This is why the nuclear bomb map radius for heat is almost always the largest circle on the screen. It reaches out much further than the physical shockwave.

The Fallout Wildcard

Fallout is the reason these maps are often scary but incomplete. Most simulators have a "fallout" toggle, but it requires you to know the wind speed and direction at 30,000 feet.

If the bomb explodes high in the air (an airburst), there is very little fallout. Why? Because the fireball doesn't touch the ground. It doesn't suck up dirt and turn it into radioactive ash. But if it’s a ground burst—meant to destroy a hardened bunker or a silo—it kicks up tons of debris. That debris becomes highly radioactive and drifts with the wind.

This creates a "plume" rather than a circle. A nuclear bomb map radius for fallout can stretch for hundreds of miles, crossing state lines and contaminating farmland long after the initial flash is over.

Modern Tools and Expert Data

We have to talk about Alex Wellerstein. He’s a historian of science at the Stevens Institute of Technology. He created NUKEMAP because he realized that people have no visceral sense of scale when it comes to nuclear weapons.

His tool uses the "DHRA" (Defense Humanitarian Relief Agency) models and equations from the 1977 book The Effects of Nuclear Weapons by Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan. It’s the gold standard. When you use these tools, you're looking at the same physics the Pentagon studied for decades.

But even Wellerstein warns that these are estimates. They don't account for "firestorms." In Hiroshima, the firestorm—a self-sustaining weather system of flame—killed more people than the actual blast. Most maps don't show that because firestorms are notoriously hard to predict. They depend on how much "fuel" (wooden houses, gas lines, cars) is in the city.

💡 You might also like: OS X Mountain Lion: Why This Forgotten Mac Update Still Defines How You Work

Practical Steps for Reality

If you’re looking at a nuclear bomb map radius because you’re genuinely worried about current events, stop looking at the rings and start looking at the "Grey Zones."

- Identify High-Value Targets: Maps usually center on city halls. In a real scenario, targets are more likely to be communications hubs, major ports, or military installations. If you live near a "Tier 1" target, your strategy is different than if you're in a suburban sprawl.

- Understand the "Flash-to-Bang": Light travels faster than sound. If you see a flash that is brighter than anything you’ve ever seen, do not look at it. You have seconds—maybe a minute—before the blast wave hits. Drop to the ground, face down, hands under your body. This protects your eyes and keeps you from being thrown.

- The "10-Minute" Rule: If you are outside the immediate "Vaporization Zone," the most dangerous thing is the fallout that starts falling 10 to 20 minutes later. It looks like sand or ash. Get inside. Get to the center of a building. Put as much mass (concrete, bricks, dirt) between you and the outside as possible.

- Don't Forget the EMP: A nuclear bomb map radius doesn't show the Electromagnetic Pulse. An airburst could fry the electronics in your car and your phone across half a continent, even if you’re nowhere near the blast rings.

These maps are incredible educational tools, but they are also a bit of a psychological trap. They make a chaotic, horrific event look orderly. They make us feel like we can "calculate" our way out of a catastrophe. Use them to understand the scale, but remember that the best way to survive a radius is to ensure the weapon is never launched in the first place.

Stay informed, but don't let the red circles keep you up at night. The math is interesting; the reality is something we should all work to keep in the realm of simulation.