Ever looked at a jumble of letters like AUG, GGC, and UAA and felt like you were staring at a broken typewriter? Honestly, that’s basically what your cells deal with every single second. But they don't panic. They use a specific map. The mRNA amino acid chart is that map, a translation dictionary that turns genetic code into the actual physical stuff you’re made of—muscles, enzymes, and even the antibodies fighting off that cold you picked up last week.

It's wild.

✨ Don't miss: Drexel University College of Medicine: What Most People Get Wrong About This Philly Powerhouse

We’re talking about a system that is almost universal across every living thing on Earth. Whether you’re a human, a housefly, or a head of broccoli, your body reads these instructions in pretty much the same way. It’s the closest thing we have to a "Source Code" for life.

The Logic Behind the mRNA Amino Acid Chart

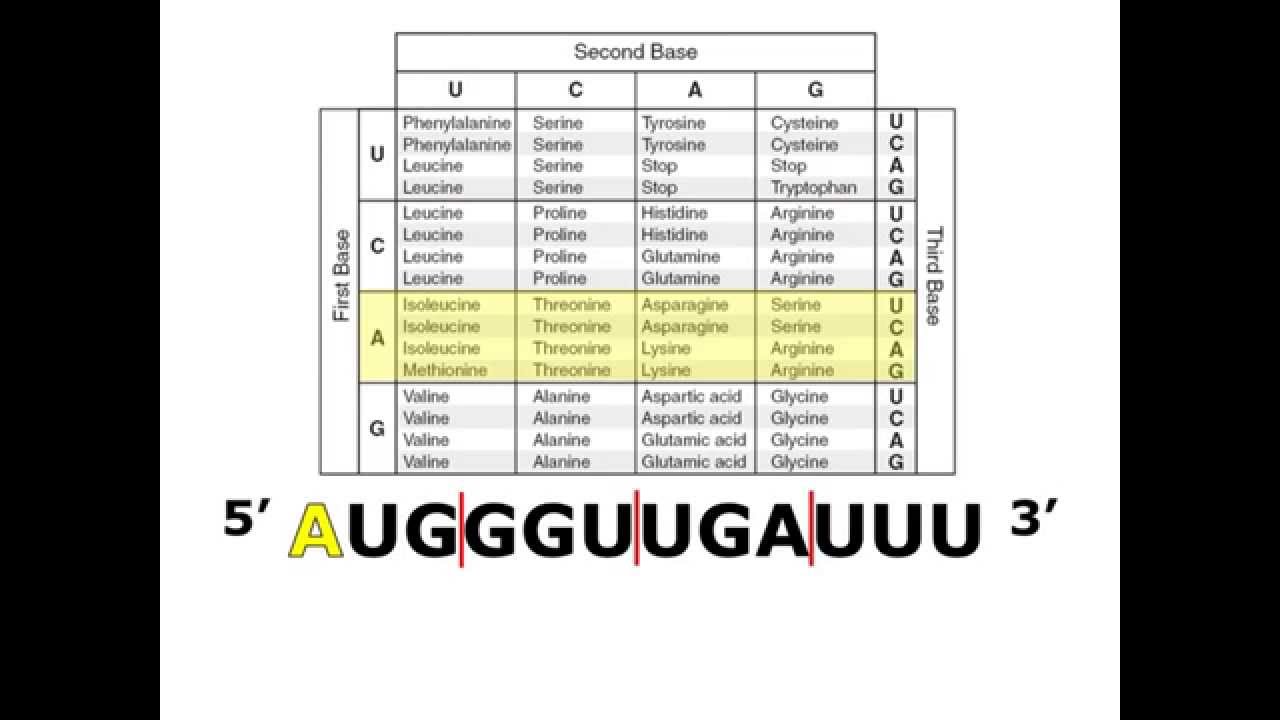

Most people get intimidated by the grid. They see 64 squares and think it’s some high-level calculus. It isn’t. Think of it like a coordinates system.

An mRNA strand is just a long chain of four bases: Adenine (A), Uracil (U), Cytosine (C), and Guanine (G). But your body doesn't read them one by one. That would be too simple, right? Instead, it reads them in groups of three. These trios are called codons.

Why three? Well, if the cell read one letter at a time, it could only make four different amino acids. If it read two at a time, it could make 16 combinations (4 x 4). But we need to build 20 different amino acids to sustain human life. By using a three-letter system, nature gives itself 64 possible combinations ($4^3$). This creates a "redundant" system.

It’s a safety net.

🔗 Read more: Walmart Hearing Aids: Why Your Local Supercenter is Suddenly a Major Player in Audiology

For example, if you look at a standard mRNA amino acid chart, you’ll notice that Leucine is coded by six different codons (UUA, UUG, CUU, CUC, CUA, and CUG). This means if a tiny mutation happens and a letter gets swapped out, there’s a decent chance the protein will still turn out exactly how it was supposed to. It's biological error-correction at its finest.

Start and Stop: The Bookends of Life

You can't just start reading a book in the middle of a random sentence. You need a capital letter. In the world of molecular biology, that "capital letter" is almost always AUG.

AUG is the Start Codon. It tells the ribosome—the cell's protein factory—to start building right here. It also codes for an amino acid called Methionine. This is why almost every protein initially starts with Methionine, though it often gets trimmed off later like a loose thread on a new shirt.

Then you have the "Stop" codons: UAA, UAG, and UGA. These don't code for any amino acid at all. They are the period at the end of the sentence. When the ribosome hits one of these, it lets go of the protein chain, and the work is done. If a mutation creates a "premature stop codon," the protein ends up too short and usually won't work. This is actually what happens in certain genetic conditions like Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

How to Actually Read the Chart Without Getting a Headache

If you're looking at a circular chart or a square grid, the trick is to work from the inside out or the left side across.

- The First Letter: Look at the left axis. Let's say your codon is CAC. You find 'C' on the left.

- The Second Letter: Look at the top axis. Find 'A'. Now you’re in the specific box where C and A intersect.

- The Third Letter: Look at the right side or the tiny letters within that box. Find 'C'.

Boom. You’ve found Histidine.

It feels like playing a very nerdy version of Battleship. But instead of sinking a ship, you're figuring out how to build a hemoglobin molecule.

Why Does This Even Matter?

You might think this is just stuff for high school biology exams. It’s not. It’s the foundation of modern medicine.

Take the recent mRNA vaccines for COVID-19. Scientists literally wrote a piece of mRNA code using this exact mRNA amino acid chart logic. They designed a sequence that told your cells to build the "spike protein" of the virus. Because we know which codons lead to which amino acids, we can essentially "program" cells to produce specific proteins for therapy.

It’s basically biological software engineering.

Misconceptions That Trip People Up

A big one: People often confuse mRNA with tRNA or DNA.

DNA uses Thymine (T) instead of Uracil (U). So, if you see a "T" on your chart, you’re looking at a DNA coding strand, not the mRNA. You have to transcribe it first. Also, tRNA is the "truck" that carries the amino acid to the factory. It has an "anticodon" that matches the mRNA. If the mRNA says GGG, the tRNA has CCC.

It’s a lock-and-key system.

Another weird detail? The code isn't perfectly universal. While it’s the same for humans, trees, and most bacteria, there are weird outliers. Some mitochondria (the powerhouses of your cells, remember?) use slightly different "dialects" of the code. For instance, in human mitochondria, UGA doesn't mean "stop"—it actually codes for Tryptophan. Life is messy and likes to break its own rules.

The Degeneracy of the Code

Scientists use the word "degenerate" to describe the genetic code, but they don't mean it’s immoral. It just means that multiple codons can lead to the same result.

Think of it like synonyms. "Fast" and "Quick" mean the same thing. In the mRNA amino acid chart, GUU, GUC, GUA, and GUG all mean "Valine."

This "wobble effect" usually happens at the third position of the codon. The first two letters are the most critical; the third one is often a bit flexible. This is why many mutations are "silent." You might have a change in your DNA, but your body never even notices because the amino acid stays the same.

Practical Steps for Mastering the Code

If you’re trying to memorize this or use it for a project, don't try to memorize all 64 combinations. That’s a waste of brain space. Instead:

- Learn the big three: Start (AUG) and the three Stops (UAA, UAG, UGA).

- Identify the patterns: Notice how the first two letters usually determine the amino acid family.

- Practice "transcribing" backwards: Take a protein sequence and try to figure out what the mRNA might have looked like.

- Use a digital tool: If you're doing actual research, tools like the NCBI Genetic Code resource are much faster than staring at a printed chart.

The mRNA amino acid chart isn't just a school subject. It is the literal blueprint of your existence. Understanding it is like finally being able to read the ingredients on the back of your own life's cereal box. You start to see how tiny shifts in a sequence—a single letter out of place—can be the difference between health and disease, or even the driver of evolution itself.

💡 You might also like: Talking About Mom and Daughter Sex: Why Honest Conversations Matter for Sexual Health

Next time you see a chart, don't see a grid. See a language. Your cells are talking; now you can finally understand what they're saying.