You've probably stared at a leg muscle anatomy diagram in a doctor's office or on a gym poster and felt immediately overwhelmed by the sheer density of the labels. It’s a mess of Latin names. Sartorius, gracilis, gastrocnemius—it honestly sounds more like a spell list from a fantasy novel than the stuff inside your thighs. But here’s the thing: understanding how these muscles actually connect isn't just for medical students or people trying to ace a kinesiology quiz. It’s for anyone who has ever felt that nagging pull in their lower back after a run or wondered why their knees click every time they stand up from a chair.

The human leg is a mechanical masterpiece, but it’s also a giant game of "telephone" where one muscle's tension screams at another muscle's tendon.

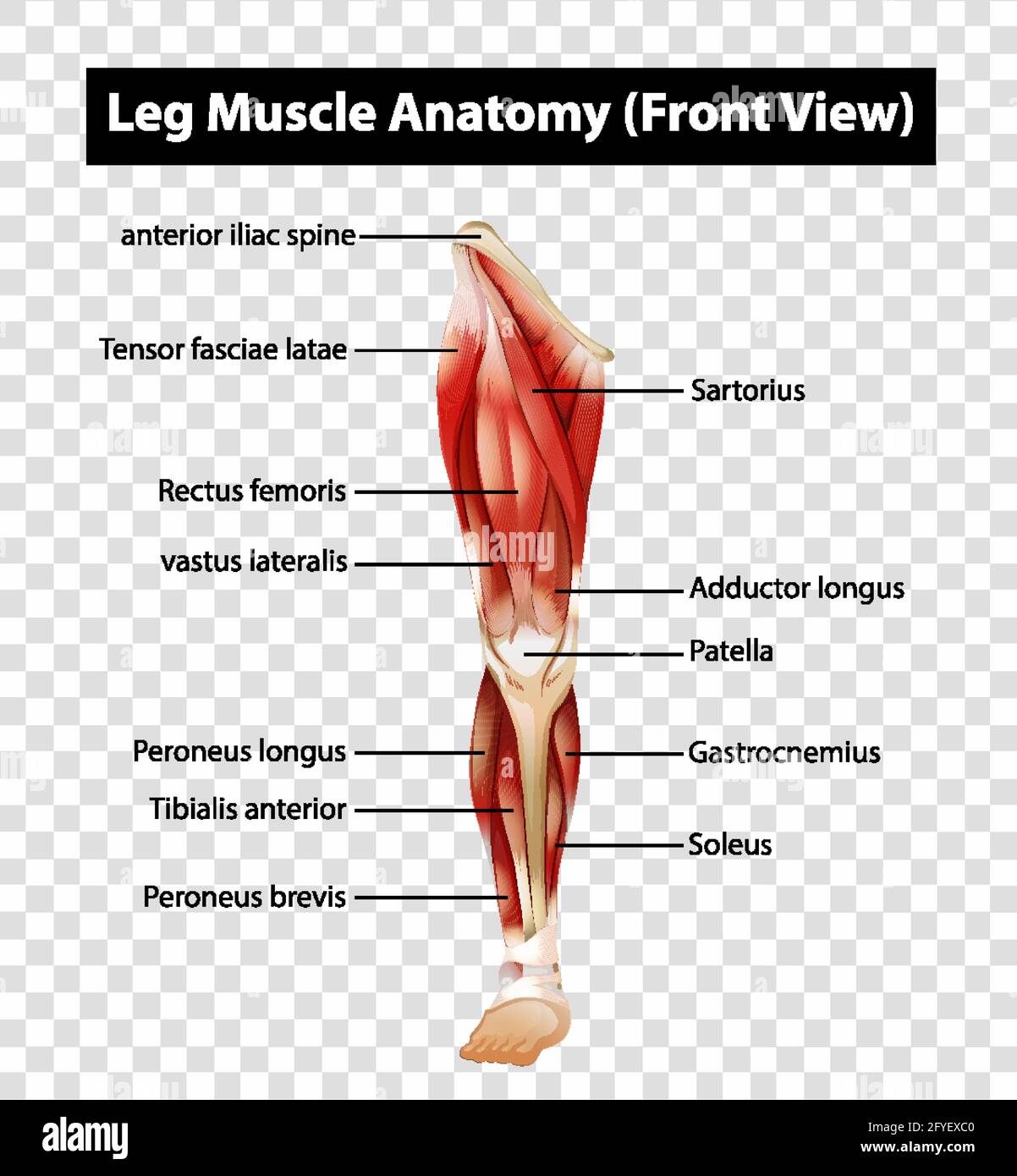

The Quads Aren't Just One Muscle

Most people point to the front of their thigh and say, "That’s my quad." Well, sort of. The quadriceps femoris is actually a group of four distinct muscles that converge into a single tendon. If you’re looking at a leg muscle anatomy diagram, you’ll see the rectus femoris sitting right on top. It’s unique because it’s the only one of the four that crosses both the hip and the knee joint. This means it helps you kick a ball, but it also helps you lift your leg toward your chest. Underneath and to the sides, you have the three "vasti" muscles: the vastus lateralis on the outside, the vastus medialis (that teardrop shape near your knee), and the vastus intermedius buried deep in the middle.

Why does this matter for your daily life? Balance.

If your vastus lateralis is way stronger than your medialis—which is super common—it can literally pull your kneecap out of its groove. It’s called patellar tracking disorder. When you see a diagram showing those muscles pulling at different angles, you start to realize why "just doing more squats" isn't always the answer to knee pain. Sometimes you need to specifically target that inner teardrop to keep the peace.

The Mystery of the Posterior Chain

Flip that leg muscle anatomy diagram around. Now we're looking at the back, the posterior chain. This is where the power lives. The hamstrings are famous, sure, but they’re also frequently misunderstood. You’ve got three of them: the biceps femoris, the semitendinosus, and the semimembranosus.

They don't just bend your knee. They are massive stabilizers for your pelvis.

🔗 Read more: What Helps Regrow Hair: Why Most Treatments Fail and What Actually Works

When people complain about "tight hamstrings," they often try to stretch them into submission. But here is a weird truth: sometimes they feel tight because they are actually overstretched and weak. If your pelvis is tilted forward—what trainers call "anterior pelvic tilt"—it pulls on those hamstrings like a guitar string. Stretching a string that’s already being pulled tight from both ends doesn't fix the tension; it just pisses off the nerve. Honestly, looking at how the hamstrings attach to the "sitting bones" (the ischial tuberosity) helps you see the physical link between your legs and your spine.

Don't Forget the Adductors and the Deep Stuff

The inner thigh is a crowded neighborhood. The adductor group—magnus, longus, and brevis—along with the gracilis, are responsible for pulling your legs together. These are the muscles that scream at you the day after you go ice skating for the first time in five years.

And then there's the lateral side. The Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL) and the Iliotibial (IT) Band.

The IT band isn't actually a muscle. It’s a thick, fibrous band of connective tissue. You can't "stretch" it any more than you can stretch a leather belt, despite what the person on the foam roller next to you says. If your leg muscle anatomy diagram shows the TFL (a tiny muscle near your hip bone) feeding into the IT band, you’ll understand that to fix IT band pain, you usually have to relax the TFL and the glutes, not mash the band itself.

The Calf Complexity

Moving down. The "calf" is really two main muscles.

The gastrocnemius is the big, double-headed one that gives the back of the lower leg its shape.

The soleus sits underneath it.

The gastroc is for explosive movement. The soleus is for endurance and steady standing.

Interestingly, when your knee is bent, the gastroc is "disarmed" because it crosses the knee joint. If you want to stretch your deep calf (the soleus), you have to do it with a bent knee. If you keep your leg straight, the gastroc takes all the load. This kind of nuance is exactly why high-quality anatomical maps are so vital for physical therapy.

Why Your Lower Back Hurts (Hint: It’s Your Hips)

The psoas major is the "soul muscle." It connects your lumbar spine directly to your femur.

It’s the primary hip flexor.

If you sit at a desk for eight hours a day, your psoas is stuck in a shortened position. It gets "tight." Because it’s literally bolted to your spine, it pulls on your lower back every time you stand up. You think you have a "back problem," but a quick look at a leg muscle anatomy diagram would show you that you actually have a "front-of-the-leg-and-hip problem."

- Rectus Femoris: Crosses hip and knee.

- Sartorius: The longest muscle in the body, running diagonally.

- Gluteus Medius: The stabilizer that stops your hip from dropping when you walk.

- Tibialis Anterior: The muscle on your shin that prevents "foot drop."

Real-world application: If you get shin splints, your tibialis anterior is likely overworked or inflamed because it's trying to lift your foot against a calf muscle that is way too tight. It's a tug-of-war. The calf is the bigger, stronger kid on the playground, and the shin is losing.

✨ Don't miss: Is Apple Cider Vinegar Good for Weight Loss? What the Science Really Says

Nuance in Anatomy

It's also worth noting that not everyone's leg muscle anatomy diagram looks the same under the skin. Human variation is real. Some people have a third "head" on their gastrocnemius. Others have slightly different insertion points for their tendons. This is why some people can squat deep with zero effort while others feel like their hips are hitting a brick wall. Bone shape—specifically the angle of the femoral neck—dictates your range of motion just as much as muscle flexibility does.

Expert sources like the Journal of Anatomy frequently publish studies on these variations. For instance, the "psoas minor" muscle is actually absent in about 40% of the human population. If you’re looking at a generic diagram and wondering why you don't feel a certain muscle "firing," it might be because your specific architecture is just a bit different.

Putting the Knowledge to Work

So, you’ve looked at the maps. You’ve seen the red and white striations of the muscle bodies and tendons. What now?

First, stop treating your muscles like isolated parts. They are part of a kinetic chain. If your ankle is stiff (looking at the talus and the surrounding ligaments), your knee has to wobble more to compensate. If your glutes are "sleepy" (a real neurological phenomenon called gluteal amnesia), your hamstrings have to do double the work to pull you up a flight of stairs.

Second, use this information to audit your movement. When you walk, are you pushing off with your big toe and engaging the calf? Or are you "clunking" along using just your hip flexors?

Practical Next Steps for Better Leg Health

To turn this anatomical theory into actual physical resilience, start with these specific focuses:

- Assess Hip Internal Rotation: Sit on a chair and see if you can swing your feet outward while keeping your knees together. If you can’t, your deep hip rotators (like the piriformis) are likely locked up, which affects every muscle shown on a standard leg diagram.

- Target the VMO: Do "terminal knee extensions" to strengthen the vastus medialis. This protects the ACL and keeps the kneecap healthy.

- Active Recovery: Use a lacrosse ball on the gluteus medius (the side of your hip). Releasing this muscle can often instantly "loosen" the hamstrings because the nervous system stops feeling the need to guard the hip joint.

- Bent-Knee Calf Stretches: Spend two minutes stretching the calves with a slightly bent knee to reach the soleus, which is often ignored in favor of the more "aesthetic" gastroc.

Understanding the layout of your own body is the difference between blindly following a workout video and actually knowing how to fix a physical "glitch." The next time you see a leg muscle anatomy diagram, don't just look at the labels. Look at the connections. Look at how the muscles overlap and realize that everything from your toes to your tailbone is essentially one long, interconnected system of levers and pulleys. Keep moving, but move with the map in mind.