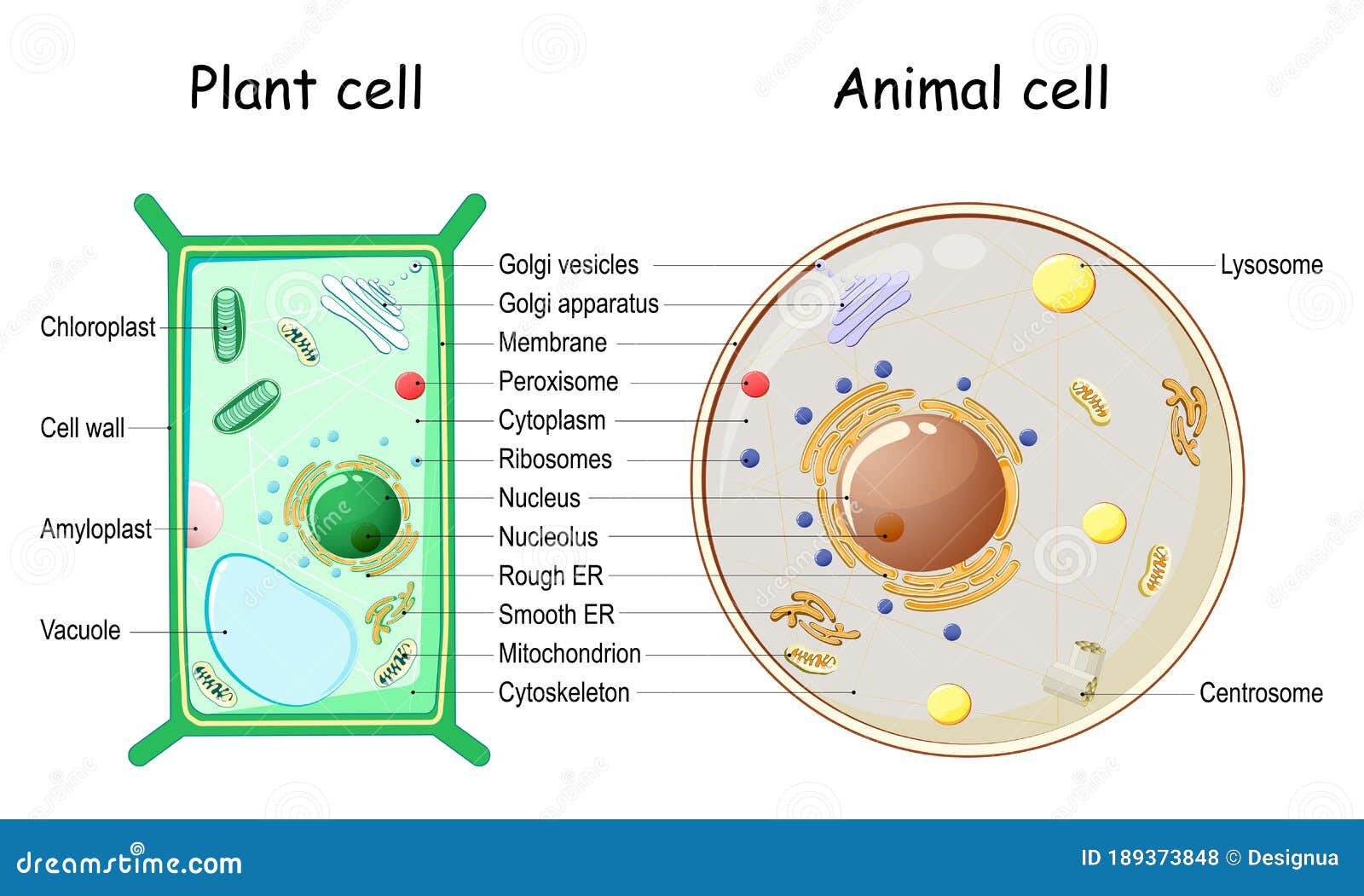

You’ve seen it. That classic, glossy image of plant and animal cell in every biology textbook since the 1990s. One looks like a green brick. The other looks like a fried egg. Honestly, it’s a bit of a lie. Cells aren't these static, colorful little drawings. They are chaotic, crowded, and constantly vibrating microscopic machines. If you actually peered through an electron microscope, you wouldn’t see those neon-pink mitochondria or bright purple nuclei. You’d see a frantic, grayish landscape of membranes and movement.

Biologists like Dr. Bruce Alberts, who literally wrote the book on molecular biology (Molecular Biology of the Cell), often point out that these diagrams are just "maps" to help us navigate the mess. But maps aren't the terrain. When we look at an image of plant and animal cell, we are looking at the fundamental blueprint of life on Earth. Everything from the moss on a rock to the person reading this screen is built from these two basic templates.

The Rigid Wall vs. The Fluid Bubble

The biggest thing that jumps out in any image of plant and animal cell comparison is the shape. Plant cells have that distinct, boxy structure. That’s the cell wall. It’s made of cellulose—basically the same stuff in your cotton t-shirt. It’s tough. It has to be. Plants don’t have skeletons, so every individual cell needs to act like a tiny brick to keep the whole tree from collapsing.

Animal cells? They’re different. They are squishy. Without that wall, they’re just held together by a thin, oily film called the plasma membrane. Think of a water balloon. It can change shape, migrate, and squeeze through tight spaces. Your white blood cells do this every day to hunt down bacteria. If you had cell walls, you’d be as stiff as a board.

But here’s a weird detail people miss: even though animal cells look "weak," they have an internal scaffolding called the cytoskeleton. It’s a mess of protein filaments like actin and microtubules. In a high-resolution image of plant and animal cell, you’d see these fibers crisscrossing the interior like the steel girders of a skyscraper. They aren't just floating bags of goo.

The Green Engine: Chloroplasts and the Energy Myth

Most people think the only difference is that plants have chloroplasts and animals don’t. That’s mostly true. Chloroplasts are the green blobs that turn sunlight into sugar. It’s the most important chemical reaction on the planet. But did you know that chloroplasts actually have their own DNA?

📖 Related: robinhood swe intern interview process: What Most People Get Wrong

Evolutionary biologists like Lynn Margulis championed the "endosymbiotic theory." Basically, billions of years ago, a larger cell swallowed a photosynthetic bacterium and, instead of digesting it, they decided to live together. That’s why when you look at an image of plant and animal cell, the chloroplasts and mitochondria look like little cells-within-cells. Because they sort of are.

Mitochondria: The Shared Powerhouse

Don't let the green stuff fool you. Both plant and animal cells have mitochondria. This is a massive point of confusion for students. Plants need mitochondria to break down the sugar they make during the day so they can survive the night. In a 3D image of plant and animal cell, you’d see dozens, sometimes thousands, of these bean-shaped power plants. They are the universal currency of life. They take oxygen and nutrients and spit out ATP. Without ATP, nothing moves. Nothing lives.

The Great Vacuole Debate

Look at a plant cell under a microscope. You’ll see a giant, clear bubble taking up almost 90% of the space. That’s the central vacuole. It’s basically a pressurized water tank. When it’s full, the plant stands tall. When it’s empty, the plant wilts. It’s also a trash can and a storage unit for pigments or poisons.

Animal cells have vacuoles too, but they’re tiny and temporary. They’re more like small "vesicles" used for transporting snacks or waste around the cell. In a standard image of plant and animal cell, the plant's vacuole looks like a massive swimming pool, while the animal's version is barely a puddle.

Why the Nucleus is the Real Star

The nucleus is the "brain," right? Sort of. It’s more like the library. It holds the DNA, which is the master set of instructions. In any decent image of plant and animal cell, the nucleus is the most prominent feature. It’s wrapped in its own double-layer membrane with tiny holes called pores.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Looking for an AI Photo Editor Freedaily Download Right Now

These pores are the bouncers of the cell. They decide what gets in and what stays out. If you look at a "fluorescence microscopy" image of plant and animal cell, the nucleus often glows bright blue because of dyes like DAPI that stick to DNA. It’s the command center. Whether you’re a dandelion or a blue whale, the nucleus tells the rest of the organelles what proteins to build and when to divide.

The Secret World of the Endomembrane System

Beyond the big names like "nucleus" and "mitochondria," there’s a whole highway system that rarely gets the credit it deserves. This is the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) and the Golgi Apparatus.

- The Rough ER: It’s covered in ribosomes, making it look bumpy or "rough" in a detailed image of plant and animal cell. This is where proteins are assembled.

- The Smooth ER: No ribosomes here. It’s all about making lipids (fats) and detoxifying stuff.

- The Golgi: Think of it as the Post Office. It takes the proteins from the ER, packages them into little bubbles (vesicles), and "ships" them to where they need to go.

In an animal cell, the Golgi is often more complex because animals have to secrete a lot of things, like hormones or digestive enzymes. In a plant cell, the Golgi (sometimes called dictyosomes) is busy building the components for the cell wall.

Centrioles and Lysosomes: The Animal Specialty

Animals have a few toys that plants usually don't. Centrioles are these weird, T-shaped structures that help with cell division. They look like little pasta tubes in a high-magnification image of plant and animal cell. Plants don't really need them to divide, which is one of those weird evolutionary quirks that scientists are still studying.

Then there are lysosomes. These are the "suicide bags" or recycling centers. They are filled with acid and enzymes that chew up old cell parts or invading viruses. While some plants have "lysosome-like" vacuoles, the true, dedicated lysosome is mostly an animal thing. It’s how we break down the food we eat at a cellular level.

✨ Don't miss: Premiere Pro Error Compiling Movie: Why It Happens and How to Actually Fix It

How Modern Technology Changed the Image

The classic image of plant and animal cell we grew up with was based on light microscopy. It was blurry. But now, we have "Cryo-Electron Microscopy." This tech won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2017. It allows us to freeze cells so fast that the water doesn't even form ice crystals.

What we see now is breathtaking. We can see individual proteins walking along the cytoskeleton. We can see the tiny motors that spin the tails of sperm cells. The "image" is no longer a drawing; it’s a high-definition movie. We’ve realized that the cytoplasm—the stuff filling the cell—isn't just water. It’s a thick, crowded jelly packed with molecules. It’s so crowded that proteins literally bump into each other millions of times a second.

Common Misconceptions to Toss Out

- "Cells are flat." Nope. They are 3D. A plant cell is more like a shoebox, and an animal cell is more like a lumpy potato.

- "Organelles just float around." They are actually tethered to the cytoskeleton. It’s more like a spiderweb than a soup.

- "The cell is the smallest unit of life." Okay, this one is technically true, but it’s misleading. A cell is a massive city of thousands of smaller parts. Even a single protein is a complex machine.

Putting This Knowledge to Use

If you’re a student, an artist, or just a curious human, don't just look at one image of plant and animal cell and think you’ve got it. Look for "Micrographs." Search for "Fluorescence imaging."

Actionable Insights for Your Next Project:

- Identify the Kingdom: If you see a thick outer border and a giant empty space in the middle, it’s a plant. If it looks like a messy, irregular blob with lots of little "bubbles," it’s an animal.

- Focus on the Nucleus: In any diagram, find the nucleus first. It’s your landmark. Everything else is organized around it.

- Check for Ribosomes: If the diagram shows dots on the nucleus-adjacent membrane, that’s the Rough ER. If not, it’s a poor-quality diagram.

- Understand Scale: Remember that millions of these can fit on the head of a pin. The "image" you see is magnified thousands of times.

The next time you look at a leaf or your own hand, try to visualize that image of plant and animal cell in your head. Realize that right now, billions of these tiny engines are burning sugar, pumping ions, and reading DNA just so you can keep breathing. It’s not just a biology lesson; it’s the most complex engineering project in the known universe.

Practical Next Steps:

- Download a Virtual Microscope App: Use tools like the "Virtual Microscope" from Open University to see real tissue samples instead of drawings.

- Search for "Inner Life of the Cell": Watch the Harvard-produced animation to see these organelles in motion. It changes everything.

- Compare Specialized Cells: Look up an image of a "Neuron" (animal) vs. a "Xylem cell" (plant). You'll see how the basic blueprint can be stretched and warped into wild new forms.