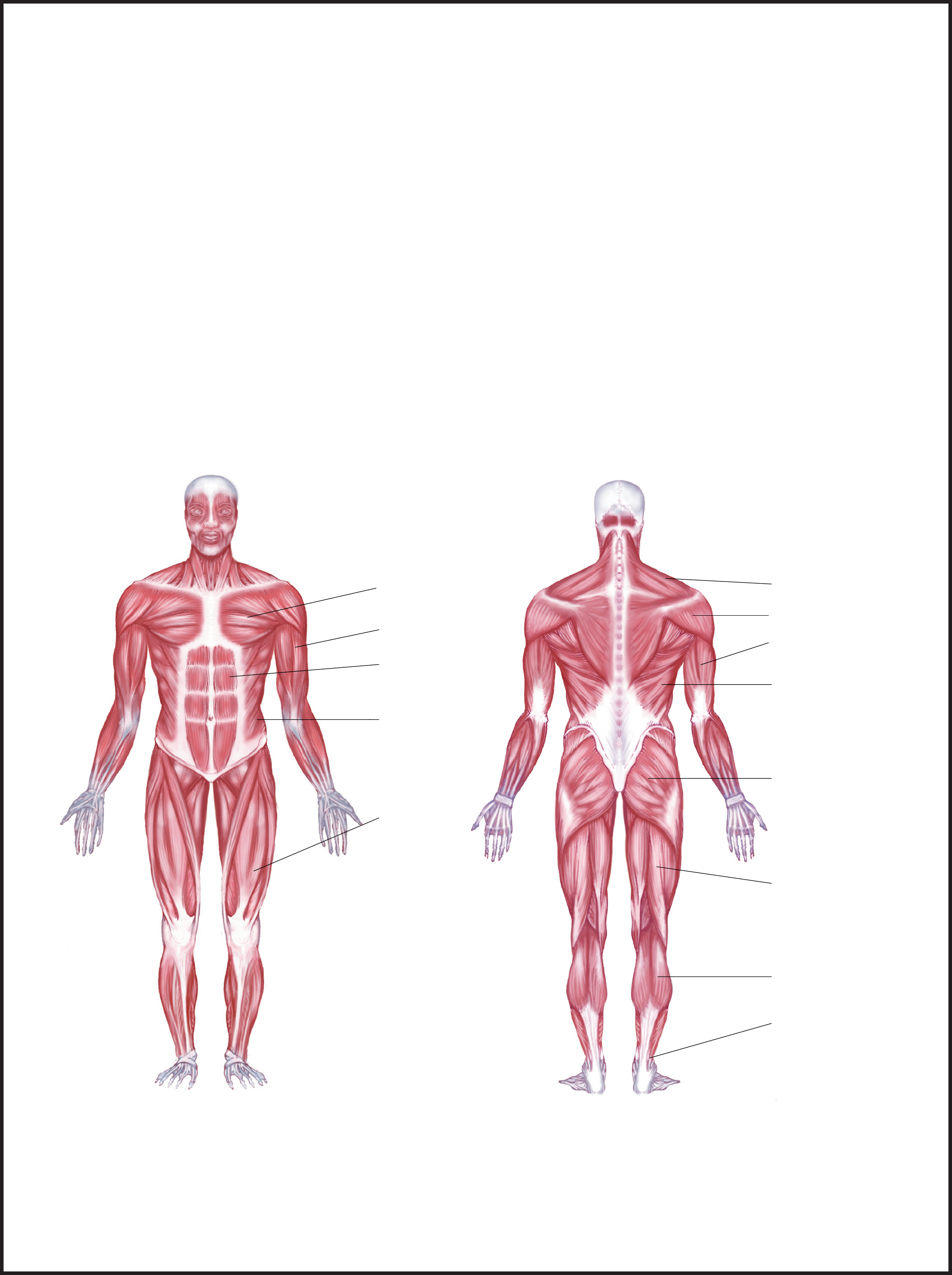

You’ve seen it. That glossy, slightly intimidating poster hanging on the wall of every physical therapy office and dusty basement gym. The human anatomy muscle chart usually features a skinless, incredibly ripped figure—often nicknamed "Muscle Man" in kinesiology circles—striking a pose that looks like a cross between a bodybuilder and a panicked traffic conductor. It’s meant to be the holy grail of "where things go." But honestly, those charts are often lying to you by omission.

They make the body look like a neat Lego set. Snap a bicep here, click a quad there.

Real life is messier. Muscles don't just sit on top of bones like stickers; they weave, overlap, and merge into fascia in ways that a 2D chart can barely capture. If you’ve ever felt a "twinge" in your lower back that somehow turned into a headache, you’ve experienced the failure of a basic wall chart to explain how your body actually functions.

Why the Human Anatomy Muscle Chart is Basically a Map (and Maps are Limited)

Think of a human anatomy muscle chart like a roadmap of a city. It shows you the highways (the big muscles like the latissimus dorsi) and the main streets (the biceps brachii). What it usually skips are the alleyways, the underground tunnels, and the weird one-way streets that actually dictate the flow of traffic.

Take the "core," for example.

Most people look at a chart, point to the rectus abdominis (the six-pack), and think that’s it. But beneath those visible ridges lies the transversus abdominis, acting like a biological weight belt. Then you have the multifidus, tiny muscles along the spine that are actually more important for back health than any crunch-induced ab muscle. If your chart doesn't show layers, you're missing half the story of why your back hurts when you sit too long.

✨ Don't miss: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

We often categorize muscles as "superficial" or "deep." The superficial ones get all the glory in the gym. They're the ones that pop. But the deep muscles—the ones the charts often hide behind the big red slabs—are the ones doing the heavy lifting for stability. Without the serratus anterior (the "boxer's muscle" along your ribs), your shoulder blade would just wing out like a broken hinge, regardless of how big your chest muscles are.

The Big Three: Muscle Groups That Rule Your Movement

When you look at a human anatomy muscle chart, your eyes usually gravity toward the "Big Three" areas. These are the zones where most injuries happen and where most strength is built.

The Posterior Chain (The Engine Room)

This is the back of your body. It includes the hamstrings, glutes, and the erector spinae. In a typical anatomical view, the gluteus maximus looks like a giant, simple lump. In reality, it’s a complex powerhouse that connects your upper and lower body. Modern sedentary life has led to what some therapists call "gluteal amnesia." Basically, your brain forgets how to fire these muscles because we spend eight hours a day sitting on them. When the glutes shut down, the lower back has to take the strain. That’s why a chart is useful—it shows you that the glutes are supposed to be the biggest muscle in the body. If yours don't feel like the biggest, you’ve got a mechanics problem.

The Shoulders and Rotator Cuff

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body. It’s also the most unstable. Most human anatomy muscle charts show the deltoid—that nice rounded cap on the shoulder. But underneath are the "SITS" muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. These are the stabilizers. If you’re lifting heavy weights but ignoring these tiny stabilizers, you’re basically putting a Ferrari engine inside a cardboard chassis. It’s going to fall apart.

The Quadriceps and Hip Flexors

The front of the thigh is dominated by the quadriceps femoris. It’s actually a group of four muscles. The rectus femoris is the tricky one because it crosses both the hip and the knee. This is why tight hips often lead to knee pain. A 2D chart shows them side-by-side, but it doesn't always convey how they pull on the patella (knee cap). If one side is tighter than the other, your kneecap tracks like a car with bad alignment.

🔗 Read more: Can DayQuil Be Taken At Night: What Happens If You Skip NyQuil

What Most People Get Wrong About Muscle Attachments

Muscles don't just float. They have "origins" and "insertions." This is where the red muscle tissue turns into white, tough tendon and anchors onto the bone.

A common misconception is that muscles only move the bone they are "on."

Not true.

The psoas major is a classic example. It starts at your lower spine, travels through your pelvis, and attaches to your femur (thigh bone). Looking at a human anatomy muscle chart, it’s hard to even see because it’s tucked so deep. But because it bridges the spine and the leg, it is the primary culprit behind "mysterious" lower back pain. You might be rubbing your back, but the problem is actually a tight muscle in your gut.

Beyond the Red: Fascia and the "Everything is Connected" Rule

If you want to be an expert on your own body, you have to look past the red muscle fibers on the chart. There is a web of connective tissue called fascia that wraps around every muscle. Think of it like the thin white film on a chicken breast.

💡 You might also like: Nuts Are Keto Friendly (Usually), But These 3 Mistakes Will Kick You Out Of Ketosis

Fascia is why a tight calf can cause plantar fasciitis in your foot or even tension in your neck.

Standard anatomical charts usually strip the fascia away to show the muscles clearly. It makes for a prettier picture, but it’s scientifically misleading. Dr. Jean-Claude Guimberteau, a renowned hand surgeon, has done incredible work filming living fascia under the skin. It looks like a chaotic, beautiful spiderweb of fluid-filled fibers. This web is what allows muscles to slide past each other. When that "web" gets sticky or dehydrated, your muscles can't move properly, even if the muscles themselves are healthy.

How to Actually Use a Muscle Chart for Self-Care

Don't just stare at the chart. Use it as a diagnostic tool. If you have a pain point, find it on the human anatomy muscle chart, then look at what is above and below it.

- Trace the line of pull. If your elbow hurts, look at the muscles of the forearm. Most "tennis elbow" isn't an elbow problem; it's a tight muscle in the top of the forearm where it attaches to the bone.

- Identify the Antagonist. Every muscle has an opposite. If your chest (pectorals) is always tight from hunching over a laptop, your back muscles (rhomboids) are likely overstretched and weak. You don't need to stretch your back; you need to strengthen it and stretch your chest. The chart helps you see these pairings.

- Check the Depth. If you’re poking at a sore spot and it feels like it's "under" the main muscle, you're likely dealing with a stabilizer. These respond better to isometric holds (holding a position) than to big, explosive movements.

The Evolution of Anatomical Mapping

We’ve come a long way from Andreas Vesalius and his 1543 masterpiece, De humani corporis fabrica. Back then, they had to steal bodies from gallows just to see what was under the skin. Today, we have 3D digital models that allow us to peel back layers in real-time.

But even with AI and 4K imaging, the basic human anatomy muscle chart remains the go-to because humans are visual creatures. We need to see the "outline" to understand the "inside."

Just remember that every body is slightly different. Some people have an extra muscle in their forearm called the palmaris longus (about 14% of people don't have it). Some people have different attachment points for their tendons, which is why some people can naturally squat deeper or throw harder. The chart is a template, not a rulebook.

Actionable Steps for Better Muscle Health

- Stop Static Stretching Cold Muscles: Use the chart to identify your "tight" areas, but don't pull on them while they're cold. Use dynamic movements (like leg swings or arm circles) to get blood into those red zones.

- Hydrate for Your Fascia: Your connective tissue is mostly water. If you’re dehydrated, your muscles literally "stick" together, making you feel stiff regardless of how much you stretch.

- Target the "Hidden" Muscles: Once a week, ignore the big muscles on the chart and focus on the small ones. Do face-pulls for your rotator cuffs or "monster walks" for your gluteus medius.

- Audit Your Posture: Look at a side-view anatomical chart. Notice the natural "S" curve of the spine. If your daily posture looks more like a "C," you are putting mechanical stress on the ligamentum nuchae at the back of your neck. Correcting this can end chronic tension headaches.

- Consult a Professional for Referred Pain: If you find a spot on the chart that looks like where your pain is, but rubbing it doesn't help, the issue is likely "referred." A trigger point in your infraspinatus (shoulder blade) often feels like pain in the front of your shoulder. A physical therapist can help you find the "source" rather than just the "symptom."

Understanding the layout of your own machinery is the first step toward longevity. The human anatomy muscle chart is your map, but your daily movement is the journey. Keep the map handy, but trust what your body is telling you over what a poster says.