Honestly, most of us haven’t looked at a diagram of the cervix and uterus since a dusty health class in middle school. You remember the one. It was a flat, purple-and-pink drawing that looked more like a steer's head than a living, breathing part of your anatomy. But here’s the thing: that diagram is the blueprint for everything from your monthly cycle to the mechanics of childbirth and even how certain cancers develop. If you’re staring at a screen trying to figure out why your pelvic exam felt weird or what a "retroverted" uterus actually looks like, you're in the right place. We're going to get into the weeds of how these organs actually sit in your body, why the cervix is basically a shapeshifter, and what the medical charts often fail to mention.

The Uterus Isn’t Just a Hollow Balloon

When you look at a standard diagram of the cervix and uterus, the uterus usually looks like an upside-down pear. It's sitting there, floating in the middle of the pelvis. In reality? It’s tucked between your bladder and your rectum. It’s a thick, muscular powerhouse. The walls are made of the myometrium—that’s the muscle that does the heavy lifting during labor—and the endometrium, which is the lining that sheds every month if an egg doesn't find a home.

The size is what usually trips people up. In someone who hasn't been pregnant, the uterus is only about 3 inches long and 2 inches wide. It's tiny. Think of a small lemon. But the way it’s positioned matters more than the size for many people. While most diagrams show it leaning forward (anteverted) over the bladder, about 25% of people have a "tipped" or retroverted uterus that leans toward the spine. If you’ve ever had a "difficult" Pap smear or felt a sharp pinch during certain yoga poses, a tipped uterus might be the culprit. Doctors like Dr. Jen Gunter often point out that a retroverted uterus is just a normal variation, like being left-handed, yet many people panic when they see it noted on an ultrasound report because the standard "perfect" diagram doesn't show it.

The Cervix: The Gatekeeper You’re Ignoring

If the uterus is the room, the cervix is the door. On a diagram of the cervix and uterus, the cervix is that narrow neck at the bottom. It’s technically the lower part of the uterus, but it acts like its own distinct organ with its own set of rules. It’s only about an inch long, but it’s arguably the hardest-working tissue in the female body.

Most of the time, the "os"—the opening of the cervix—is tiny. Like, "can barely fit a toothpick" tiny. But its texture changes based on where you are in your cycle. If you were to feel it (which you can!), it feels like the tip of your nose most of the time—firm and rubbery. When you’re ovulating, though, it gets soft, like your lips, and moves higher up in the vaginal canal to make things easier for sperm. This isn't just trivia; it's the basis of the Creighton Model and other fertility awareness methods used by millions to track reproductive health.

📖 Related: Orgain Organic Plant Based Protein: What Most People Get Wrong

The Squamocolumnar Junction: Where the Action Is

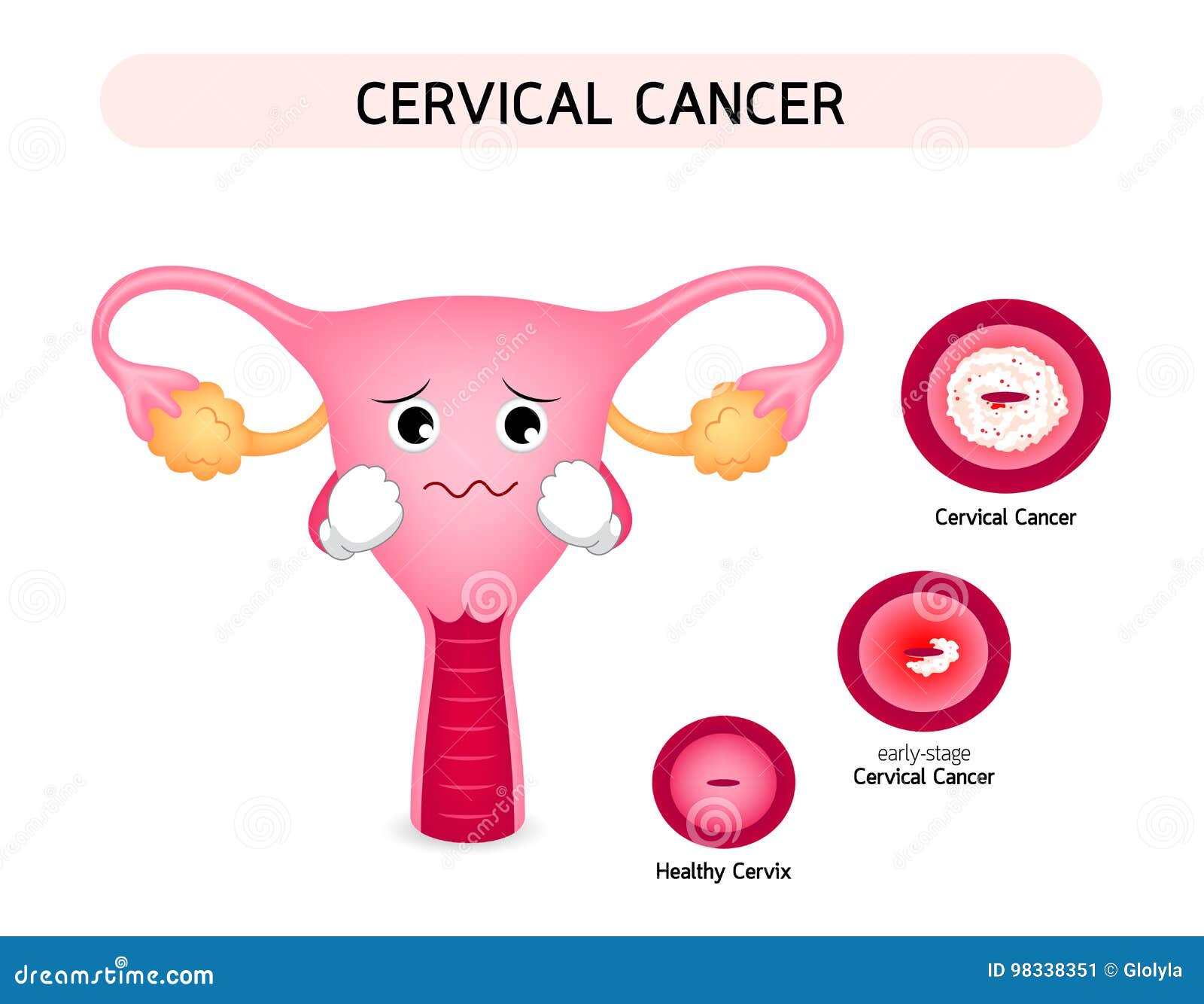

This is a mouthful, I know. But if you’re looking at a medical diagram of the cervix and uterus because of an abnormal Pap smear, this is the only part that matters. There are two types of cells on the cervix:

- Squamous cells: Flat, skin-like cells on the outside (exocervix).

- Columnar cells: Tall, gland-like cells on the inside (endocervix).

The place where these two meet is the Transformation Zone. This is where 90% of cervical cancers and precancerous changes happen. Why? Because these cells are constantly "transforming" from one type to another. It’s a high-activity construction zone, and whenever cells are dividing that fast, there’s a higher risk of things going sideways if HPV (Human Papillomavirus) is present.

What the Standard Diagrams Get Wrong About Space

In a textbook, everything is spaced out beautifully. In your actual body, there is no empty space. Everything is touching. The uterus is held in place by a complex web of ligaments—the broad ligament, the round ligament, and the uterosacral ligaments.

Have you ever felt a sharp, stabbing pain in your lower groin when you sneeze or get up too fast while pregnant? That’s the round ligament stretching. A 2D diagram of the cervix and uterus usually hides these "guy-wires" that keep the organ centered. When these ligaments get lax—sometimes due to age, multiple pregnancies, or just genetics—you get pelvic organ prolapse. This is when the "door" (cervix) starts to slide down the hallway (vagina). It’s incredibly common, yet the diagrams we see make it look like the uterus is bolted to the spine. It’s not. It’s more like it’s suspended in a hammock.

👉 See also: National Breast Cancer Awareness Month and the Dates That Actually Matter

The Role of Cervical Mucus

Diagrams rarely capture the fluid dynamics of the cervix. It’s not just a dry plug of tissue. The cervix produces mucus that changes consistency throughout the month. Under the influence of estrogen, the mucus becomes "egg-white" stretchy. If you looked at this under a microscope—which many fertility experts do—you’d see it forms tiny channels that literally act as a slip-and-slide for sperm. Without this specific biological "grease," the journey to the uterus would be impossible because the vaginal environment is naturally too acidic for sperm to survive.

When Things Look Different: Fibroids and Polyps

If you look at a diagram of the cervix and uterus and then look at your own ultrasound, you might see "lumps." These are usually fibroids. Over 70% of women will have them by age 50. They aren't cancerous, but they can turn that "pear-shaped" organ into something that looks like a bag of marbles.

Fibroids can grow:

- Intramural: Inside the muscular wall.

- Submucosal: Bulging into the uterine cavity (these cause the heavy bleeding).

- Subserosal: On the outside of the uterus, pressing on your bladder or bowels.

Understanding where these sit on the diagram helps explain why one person with a 5cm fibroid feels nothing, while someone with a 2cm fibroid is heading for surgery. Location is everything.

✨ Don't miss: Mayo Clinic: What Most People Get Wrong About the Best Hospital in the World

Navigating Your Next Step

If you’ve been studying a diagram of the cervix and uterus because something feels "off," don't settle for a generic Google search. Your anatomy is dynamic. It changes every 28 days. It changes after a workout. It definitely changes after a baby.

Actionable Insight: How to use this knowledge.

- Check your records: Look at your last pelvic ultrasound or Pap smear report. See if it mentions "anteverted" or "retroverted." Knowing your tilt can make your next exam more comfortable if you tell the provider beforehand.

- Track the "Gatekeeper": If you’re trying to conceive or just want to know your body, start noticing cervical position and mucus. It’s a more accurate real-time indicator of your hormones than many smartphone apps that just guess based on your last period.

- Screening is specific: Remember that the Pap smear only samples the cervix. It does not check the uterus or ovaries. If you have weird bleeding but a "normal" Pap, you still need to talk to a doctor about the rest of the diagram—the uterine lining itself.

- Pelvic Floor Health: Since the uterus and cervix are suspended by ligaments and muscle, if you feel "pressure," see a pelvic floor physical therapist. They are the true experts at the 3D map of your internal organs.

Your body isn't a static drawing in a textbook. It’s a moving, shifting system. Understanding the layout is just the first step in actually listening to what it’s trying to tell you.