Heart failure isn't a sudden stop. It’s more of a slow, relentless fatigue of the muscle. When you're looking at a congestive heart failure concept map, you aren't just looking at a medical diagram; you're looking at a web of cause and effect that determines whether a patient goes home or stays in the ICU. It's complex. Honestly, the sheer volume of data involved in cardiac care is enough to make any nursing student or resident's head spin.

The heart fails. That’s the "what." But the "why" and the "how" are where things get messy.

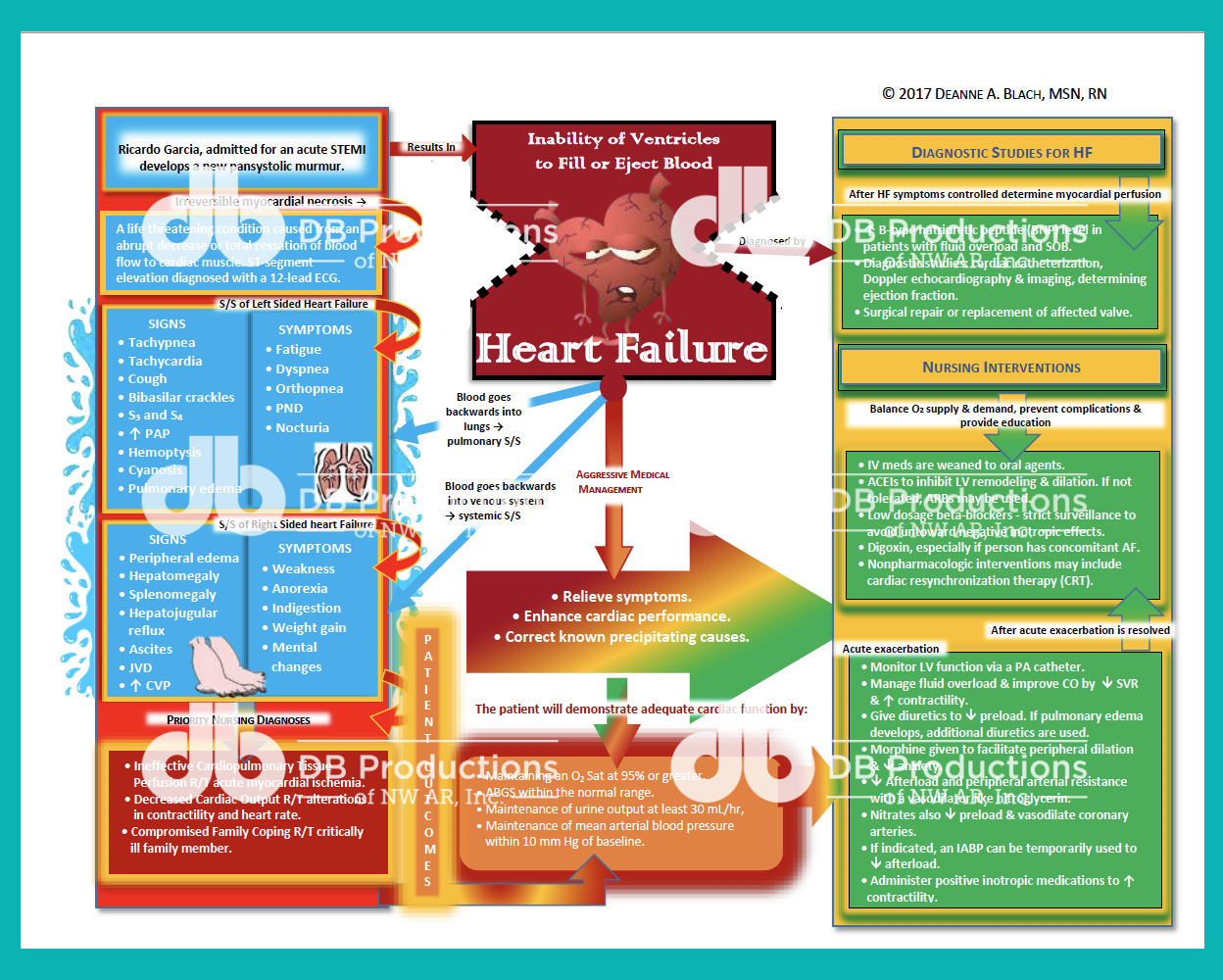

Basically, a concept map serves as a cognitive bridge. It connects the primary diagnosis—Congestive Heart Failure (CHF)—to the sprawling mess of symptoms like peripheral edema, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and decreased cardiac output. If you can’t see how a high-sodium diet directly triggers the fluid volume excess that leads to crackles in the lungs, you're going to miss the mark on treatment.

The Anatomy of a High-Functioning Congestive Heart Failure Concept Map

A good map starts in the center with the pathophysiology. You've got two main flavors: systolic and diastolic. In systolic failure, the heart is too weak to pump. Think of a worn-out rubber band. In diastolic failure, the heart is too stiff to fill. That’s more like a rusted spring.

From that center point, the map should bleed out into four specific quadrants: Assessment, Nursing Diagnosis, Interventions, and Evaluation.

Most people screw this up by making it too linear. It’s not a straight line. It’s a loop. If you administer a loop diuretic like Furosemide (Lasix), your map has to show a line connecting back to potassium levels. Why? Because you're literally flushing electrolytes down the toilet along with the fluid. If you don't visualize that connection, you forget to check the labs, and suddenly your patient has an arrhythmia because their potassium hit the floor.

Why Your Assessment Data Needs to Be Granular

Don't just write "shortness of breath." That's lazy. On a professional congestive heart failure concept map, you need to distinguish between dyspnea on exertion and orthopnea.

Can the patient sleep flat? No? They need three pillows? That’s a specific clinical marker.

- Left-sided failure usually means lung issues. Think Drowning. The blood backs up into the pulmonary veins. You’ll hear those wet, bubbly sounds—crackles—at the bases of the lungs.

- Right-sided failure is about the body. This is where you see the "Elephant Legs" (pitting edema) and the distended jugular veins.

When you're mapping this out, draw a physical line between left-sided failure and right-sided failure. Because, guess what? The most common cause of right-sided heart failure is actually left-sided heart failure. The pressure just keeps backing up until the whole system is under water.

📖 Related: Dr. Sharon Vila Wright: What You Should Know About the Houston OB-GYN

The Pharmacological Tangent

Let’s talk meds. This is where the concept map gets crowded. You’ve got the "Triple Threat" of CHF management: ACE inhibitors, Beta-blockers, and Diuretics.

ACE inhibitors (like Lisinopril) are there to stop the RAAS system. The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System is basically the body’s panicked overreaction to low blood pressure. It holds onto salt and water, which is the last thing a failing heart needs. It’s like trying to help a drowning man by throwing him a bucket of water.

Then you have Beta-blockers. These are tricky. They slow the heart down. In the short term, it sounds counterintuitive to slow down a weak heart. But in the long run, it prevents the heart from "working itself to death."

On your congestive heart failure concept map, you must link Beta-blockers to "Heart Rate" and "Blood Pressure" monitoring. If the pulse is 52, you don't give the med. Simple. But if it's not on your map, it's easy to overlook during a chaotic 12-hour shift.

The Patient Perspective: More Than Just Charts

We often forget the "Lifestyle" branch. Honestly, this is where most readmissions happen. A patient goes home, eats a bag of salty potato chips because they weren't educated properly, and they’re back in the ER three days later.

A comprehensive map includes:

- Daily weight monitoring (The "2lbs in a day, 5lbs in a week" rule).

- Fluid restriction (usually around 1.5 to 2 liters).

- Sodium limits (staying under 2,000mg).

If the patient doesn't understand that salt follows water, the medical interventions won't matter. The map should show "Patient Education" as a core pillar, not an afterthought.

Common Pitfalls in Visualizing CHF

One major mistake is ignoring the kidneys. The heart and kidneys are like a toxic couple; when one goes down, they try to take the other with them. This is called Cardiorenal Syndrome.

👉 See also: Why Meditation for Emotional Numbness is Harder (and Better) Than You Think

In your congestive heart failure concept map, you need a dedicated section for BUN and Creatinine levels. When cardiac output drops, the kidneys don't get perfused. They get angry. They stop filtering. Now you have a patient with heart failure and acute kidney injury. It's a nightmare to manage because the treatment for one often hurts the other.

Another thing? Depression.

It sounds "soft" compared to Ejection Fractions and BNP levels, but it's vital. Patients with CHF have incredibly high rates of clinical depression. When you're too tired to walk to the mailbox, life feels pretty bleak. A map that ignores the psychosocial aspect isn't a map of a human—it's a map of a machine. And humans don't follow algorithms perfectly.

Using the BNP Level as a North Star

Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) is the "stretch" hormone. When the ventricles are stretched too thin by extra fluid, they secrete BNP.

- Under 100? You're probably fine.

- Over 900? You're in a full-blown exacerbation.

In the context of a congestive heart failure concept map, BNP should be linked directly to "Fluid Volume Excess." It is the most objective way to tell if your interventions—those diuretics we talked about—are actually working. If the BNP is trending down, you’re winning. If it’s climbing, you need to rethink the map.

Actionable Next Steps for Creating Your Map

Creating one of these isn't just a homework assignment; it's a strategy for clinical competence.

Start with the primary trigger. Was it an MI (heart attack)? Long-term hypertension? Viral myocarditis? The "Entry Point" changes the focus of the care.

Layer your symptoms. Group them by system (Respiratory, Integumentary, Renal). This helps you notice patterns during a physical exam.

Map the "If/Then" scenarios. - If the patient is dizzy... Then check blood pressure (could be the ACE inhibitor).

✨ Don't miss: Images of Grief and Loss: Why We Look When It Hurts

- If the patient has a dry cough... Then check if they just started an ACE inhibitor (a common side effect).

- If weight increases by 3 pounds... Then increase diuretic dose (per standing orders).

Don't be afraid of messy connections. The body is messy. Your map should have arrows crossing each other. It should show that the lungs affect the heart, the heart affects the kidneys, and the kidneys affect the blood chemistry.

Ultimately, the goal of a congestive heart failure concept map is to move from "reactive" care to "proactive" care. You want to see the fluid building up before the patient starts gasping for air. You want to see the potassium dropping before the heart skips a beat.

Use a large whiteboard or a digital mapping tool. Color-code your interventions: red for "Emergency/Stat," blue for "Maintenance," and green for "Education." This visual hierarchy allows you to prioritize your day. In a clinical setting, priority is everything. You can't do everything at once, so you have to do what keeps the patient alive first.

Stop treating CHF as a single problem. It's a systemic failure. The map is your GPS through that failure. Use it to keep your patient on the road to stability.

Focus on the trends, not just the single data points. A single blood pressure reading is a snapshot; a concept map is the whole movie. Watch the movie.

To wrap this up, prioritize these three things when you sit down to draw your map:

- Identify the "Why": Determine if it's a filling problem or a pumping problem.

- Track the Fluid: Connect sodium intake, weight gain, BNP levels, and lung sounds into one cohesive "Fluid Loop."

- Monitor the Meds: Create "watchdog" links for every drug—specifically checking electrolytes for diuretics and heart rate for beta-blockers.

By following this structure, you turn a confusing diagnosis into a manageable plan of action.