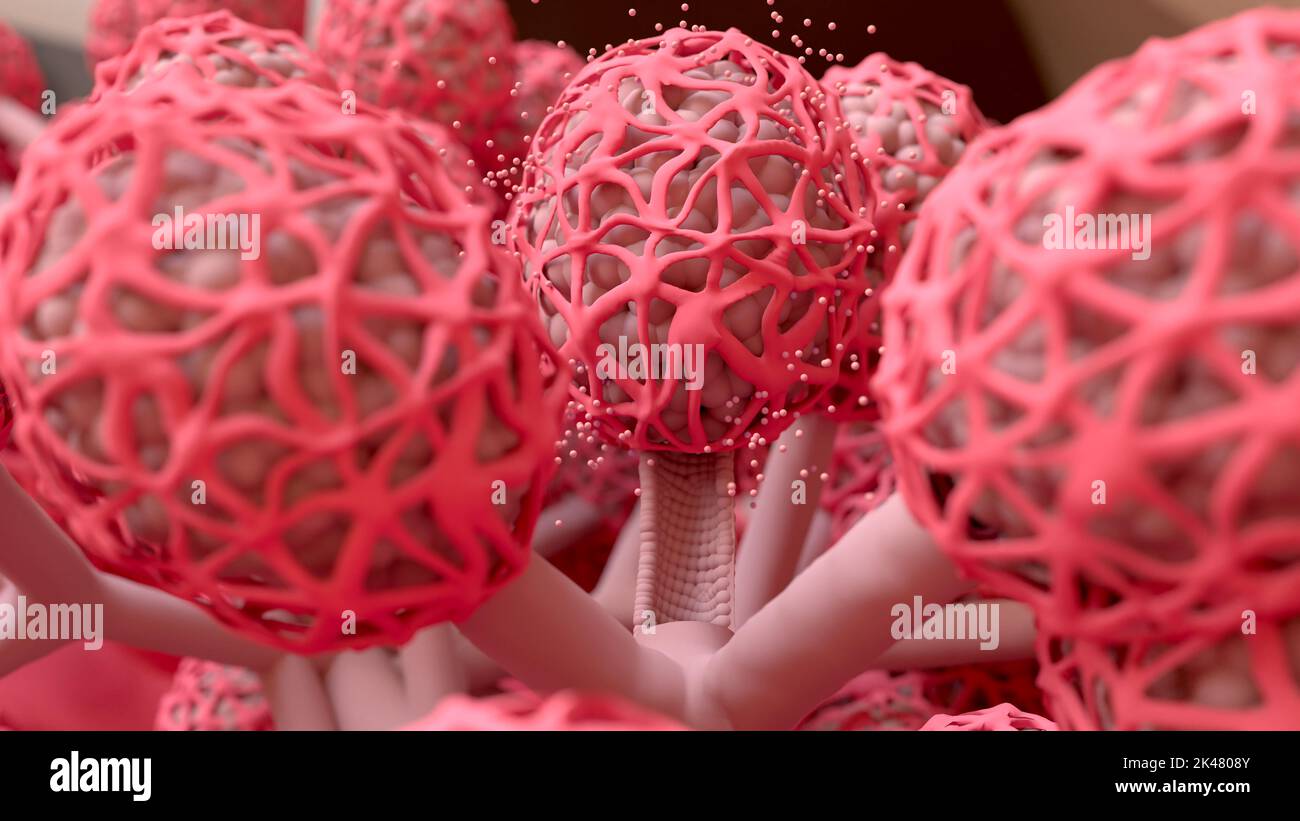

If you spent any time on social media back in 2019, you probably remember that one image. It looked like a bunch of red, flower-shaped petals tucked inside a breast. People were freaking out. Some thought it was beautiful; others said it looked like a "nightmare fuel" alien organism. Honestly? It wasn't even an accurate breast milk ducts diagram.

That viral image was actually a 3D rendering of muscle structure, not the complex plumbing that actually makes breastfeeding possible.

When we talk about how milk gets from point A to point B, the reality is way more interesting than a CGI flower. It’s a dynamic, living system that changes every single day depending on how much your baby eats. Understanding the layout of your milk ducts isn't just for medical students. It’s actually pretty vital for anyone trying to navigate mastitis, clogged ducts, or just the weirdness of how let-down feels.

The Anatomy Reality Check

Most old-school textbooks show the breast as a neat, symmetrical organ. They draw these perfect little "sinuses" right behind the nipple where milk supposedly pools, waiting to be sucked out.

Well, modern ultrasound research says that's basically a myth.

In 2005, Dr. Donna Geddes and her team at the University of Western Australia used high-res ultrasound to look at lactating breasts. They realized that the "milk sinuses" we all saw in every breast milk ducts diagram for a century don't actually exist. Instead, the ducts are small, superficial, and they branch out immediately. They aren't storage tanks. They are high-speed pipes.

This matters. If you think there are big reservoirs behind the nipple, you might try to "drain" them by squeezing that specific area. But since the ducts are actually tiny and spread out like tree roots, that kind of pressure can actually cause bruising or inflammation.

Why the Tree Metaphor Works Best

Think of it like a willow tree.

The "trunk" is the nipple. But instead of one big tube, there are usually between 4 and 18 tiny openings on the surface of the nipple. These are the ductal openings. They’re so small you can barely see them unless milk is actively coming out. From those openings, the ducts branch out deep into the fatty tissue.

At the very ends of these branches are the alveoli. These are the grape-like clusters where the magic happens. This is where your blood's nutrients are literally transformed into human milk.

🔗 Read more: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

How the Duct System Actually Functions

It isn't a passive straw. It's a pump.

When a baby latches or you start a pump, your brain releases oxytocin. This hormone causes the tiny muscles surrounding those grape-like alveoli to squeeze. This is the "let-down reflex." It pushes the milk out of the clusters and into the ducts.

The ducts then expand.

Because the ducts are elastic, they widen to accommodate the flow of milk moving toward the nipple. If you've ever felt a tingle or a sharp "pins and needles" sensation, that’s literally your ductal system shifting gears.

Sometimes the system gets backed up. You've probably heard of a "clogged duct."

People used to think a clog was like a literal plug of dried milk stuck in a pipe. You’ll still see people online suggesting you "poke it with a needle" or "massage it hard." Please don't do that.

Current medical consensus—specifically from the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine—has shifted. They now view "clogs" more as ductal inflammation. The tissue around the duct gets swollen and puts pressure on the tube, narrowing it so milk can't pass. It's like a kink in a garden hose. If you massage it aggressively, you’re just smashing inflamed tissue, which makes the swelling worse.

Instead of "beating up" the clog, the new protocol is "AIS" (Anticipatory Guidance, Ice, and Soft Touch). Think of it like a sprained ankle. You wouldn't "deep tissue massage" a fresh sprain, right? You'd use ice and ibuprofen to bring the swelling down so the milk can flow again on its own.

Different Bodies, Different Diagrams

One thing a standard breast milk ducts diagram won't tell you is that no two systems look alike.

💡 You might also like: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

Some people have ducts that are very close to the skin. These folks might find that a bra that’s too tight or a heavy purse strap causes a clog almost instantly. Others have ducts buried deep under layers of adipose tissue (fat).

The storage capacity varies wildly too.

- Some women have a "large storage capacity." Their ducts and alveoli can hold a lot of milk between sessions.

- Others have a "small storage capacity."

This has nothing to do with breast size. You can have a large breast with low storage capacity or a small breast with high capacity. Someone with a smaller capacity isn't making less milk over a 24-hour period, but their "pipes" fill up faster. They might need to feed or pump more often because their "tank" is full, whereas someone with a large capacity can go longer between sessions without feeling discomfort or signaling their body to slow down production.

Common Misconceptions found in Breast Milk Ducts Diagrams

We need to talk about the "Cooper’s Ligaments."

In many diagrams, you’ll see these wavy lines that seem to hold everything up. These are the connective tissues. They weave in and around the milk ducts. While they don't produce milk, they are the structural framework. When the ducts fill with milk, they put weight on these ligaments.

There’s also the myth of the "blocked nipple pore."

Sometimes you’ll see a white dot on the nipple, often called a bleb. While it looks like the end of a duct is "capped," it’s often just a tiny bit of overgrowth of skin or a localized inflammatory response. Again, the old advice was to pop it. The new advice? Leave it alone. Use a warm compress. Let the pressure of the milk flow from the inside do the work.

Technical Nuance: The Role of Myoepithelial Cells

If we were to zoom in on a high-detail breast milk ducts diagram, we’d see the myoepithelial cells. These are the "movers."

They wrap around the alveoli like a mesh bag. When oxytocin hits, these cells contract. If you are stressed, cold, or in pain, your body produces adrenaline, which can actually inhibit these cells from squeezing. This is why you might feel full but "nothing is coming out." The ducts are fine, the milk is there, but the "squeezers" are locked up.

📖 Related: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

Understanding this helps you realize that breastfeeding is as much a neurological process as it is a physical one.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Your Anatomy

If you are currently lactating or preparing to, don't rely on those "flower" pictures. They give you a false sense of where the milk is. Instead, try these steps to actually work with your anatomy:

1. Map your own "flow" through feel.

Instead of looking at a generic breast milk ducts diagram, use light finger-tip pressure when you are full. You can often feel the "fullness" radiating back toward your armpit. This is the Tail of Spence, an extension of breast tissue that goes up into the axilla. Many people get "clogs" here because they don't realize milk ducts extend that far.

2. Use the "Dangle" technique for gravity.

If you do have an area of inflammation, use gravity to your advantage. Leaning over your baby or the pump allows the ducts to hang straight. This can reduce the "kinks" in the system caused by the weight of the breast tissue itself.

3. Gentle lymphatic drainage over deep massage.

Since we now know "clogs" are often just swollen tissue, use "petrissage"—very light, sweeping motions from the nipple back toward the chest and armpit. This moves excess fluid (lymph) away from the ducts, giving them room to expand and let milk through.

4. Check your flange size with a ruler.

Because the ductal openings on the nipple are so specific, a pump flange that is too big or too small will rub against those openings. This causes the tissue to swell shut. Measure your nipple diameter (not the areola) to ensure the "entry point" of your ductal system isn't being constricted.

The human breast is a remarkably adaptable organ. It’s not a static machine; it’s a responsive, branching network that reorganizes itself every time a person becomes pregnant. By moving away from the "petal" diagrams and understanding the ductal system as a flexible, easily-inflamed network of tiny tubes, you can better manage your health and comfort.

Stop thinking of it as a plumbing problem and start thinking of it as a tissue management problem. Your ducts will thank you.