You’ve probably been there. You write a script that works perfectly on your laptop with ten rows of data. It’s fast. It’s elegant. Then, you push it to production, hit a million records, and the whole thing grinds to a halt. This isn't just bad luck; it’s math. Specifically, it’s the math visualized in a big o notation graph. If you haven't looked at one lately, it’s basically a map of how much your software is going to suffer as it grows.

Computers are fast, but they aren't infinitely fast.

The Curve of Pain: Reading the Big O Notation Graph

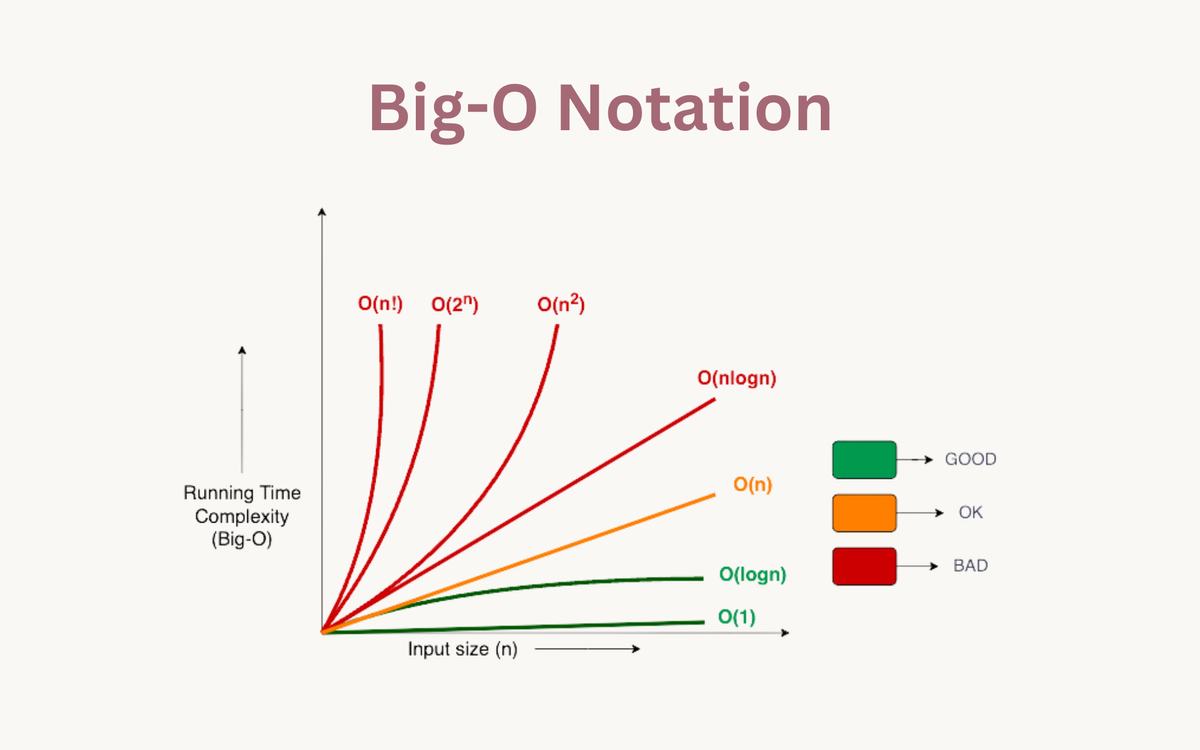

When we talk about performance, we usually talk about "time complexity." It’s a fancy way of saying "how many steps does this take?" A big o notation graph plots the number of operations on the vertical axis against the size of the input, usually called $n$, on the horizontal axis.

The shapes on this graph tell the story of your career as a developer. Some lines stay flat. Some go up in a straight, predictable line. Others shoot toward the moon like a panicked stock market chart. Honestly, if your code’s performance looks like a vertical wall, you're in trouble.

The "Good" Zone: Constant and Logarithmic Time

At the very bottom of the graph, barely hugging the horizontal axis, is $O(1)$. This is constant time. It doesn't matter if you have ten items or ten billion; the time it takes is the same. Accessing an element in an array by its index? That's $O(1)$. It’s the gold standard.

Then you have $O(\log n)$. This is the "Logarithmic" curve. It goes up, sure, but it levels off fast. Think of a binary search. If you double the amount of data, you only add one extra step. It’s incredibly efficient. Most high-performance databases rely on B-Trees or similar structures specifically to keep operations in this zone.

The "Danger" Zone: Where Things Get Messy

The middle of the big o notation graph is dominated by $O(n)$, or linear time. It’s a 45-degree angle. If you have twice as much data, it takes twice as long. Simple. Fair. Predictable. A single for loop through a list is the classic example.

But then we hit $O(n \log n)$. This is the standard for efficient sorting algorithms like Mergesort or Heapsort. It’s slightly worse than linear, but still manageable for most large-scale applications.

When the Graph Hits the Ceiling

If you see $O(n^2)$ on your graph, you should probably start worrying. This is quadratic time. It usually happens when you have nested loops—looping through a list, and for every item, looping through that same list again.

👉 See also: iPhone 14 New Features: What Most People Get Wrong

Imagine you have 1,000 items.

$1,000^2$ is 1,000,000.

That’s a million operations for a relatively small dataset.

If $n$ grows to 100,000? You’re looking at 10 billion operations.

Your CPU is going to start heating up your coffee.

Exponential and Factorial Nightmares

The real "no-go" zones are $O(2^n)$ and $O(n!)$. On a big o notation graph, these lines basically go straight up. These are often found in "brute force" solutions to complex problems, like the Traveling Salesperson Problem or recursive Fibonacci sequences without memoization.

If you’re writing code that hits $O(n!)$, and $n$ is bigger than 20, the universe might end before your program finishes. Seriously.

Why Real-World Hardware Muddies the Waters

Graphs are clean. Reality is messy.

In a textbook, $O(1)$ is always better than $O(n)$. But in the real world, constants matter. If your $O(1)$ operation takes an hour (maybe it’s a very slow network call) and your $O(n)$ operation takes a microsecond, the linear approach is better for any $n$ you’ll actually encounter.

Engineers like Donald Knuth have often pointed out that Big O describes asymptotic behavior—what happens as $n$ approaches infinity. But we don't live in infinity. We live in 64GB of RAM and 4GHz clock speeds.

Sometimes, a "theoretically" slower algorithm wins because it uses the CPU cache more effectively. Linear scans of memory are often faster than jumping around pointers in a "faster" tree structure because of how modern hardware fetches data in blocks.

Practical Steps to Optimize Your Performance

Don't just stare at the graph; change your code. If you find yourself stuck in a high-complexity mess, there are usually three ways out.

First, look for redundant work. Are you calculating the same value inside a loop over and over? Move it out. This doesn't change the Big O, but it lowers the "constant factor," which is the real-world time your user feels.

🔗 Read more: iPad Pro 11 inch 4th generation: Why This M2 Tablet is Still the Sweet Spot

Second, use better data structures. This is where you actually move down the big o notation graph. Replacing a List with a Hash Set can turn an $O(n)$ search into an $O(1)$ search. That is a massive, structural win.

Third, consider "Divide and Conquer." Many $O(n^2)$ problems can be broken down into $O(n \log n)$ problems by splitting the data into smaller chunks, solving them, and merging them back together.

Stop Guessing and Start Measuring

Never optimize based on a "hunch." Use a profiler.

Tools like cProfile for Python, Chrome DevTools for JavaScript, or pprof for Go will show you exactly which line of code is eating your cycles. Often, the bottleneck isn't where you think it is. You might spend all day optimizing a loop that only runs ten times, while a "hidden" $O(n)$ operation inside a library call is actually what’s killing your performance.

The big o notation graph is a tool for thought, not a replacement for measurement. Use it to predict how your system will behave next year when you have ten times the users. If your growth plan puts you on a vertical line, it’s time to rewrite your core logic before the server melts.

Your Next Moves for Scalable Code

Start by auditing your most frequent loops. Look for any nested iterations that could be replaced by a Map or Dictionary lookup. If you’re dealing with massive datasets, investigate whether you can trade space for time—using more memory to store a cache or index can often drop your complexity from quadratic to linear. Finally, always test your code with "production-sized" data in a staging environment; a graph on a whiteboard is no substitute for a stress test.