If you look at a Battle of Verdun map today, it looks like a messy thumbprint of chaos on the edge of France. It doesn't look like a strategic masterpiece. Honestly, it looks like a suicide note written in trenches. For 302 days in 1916, the German and French armies threw millions of shells at a tiny patch of land that, strategically speaking, wasn't even the most important spot on the Western Front. But symbols matter. Verdun was a fortress city, a point of French pride, and General Erich von Falkenhayn knew it. He didn't want to capture the city as much as he wanted to "bleed France white."

The geography is the first thing you notice. The Meuse River cuts right through the sector, creating a natural divide that made logistics a nightmare. Imagine trying to move thousands of tons of ammunition across a single bridge while German Krupp guns are literally raining fire on your head. That was the reality.

The Brutal Geometry of the Battle of Verdun Map

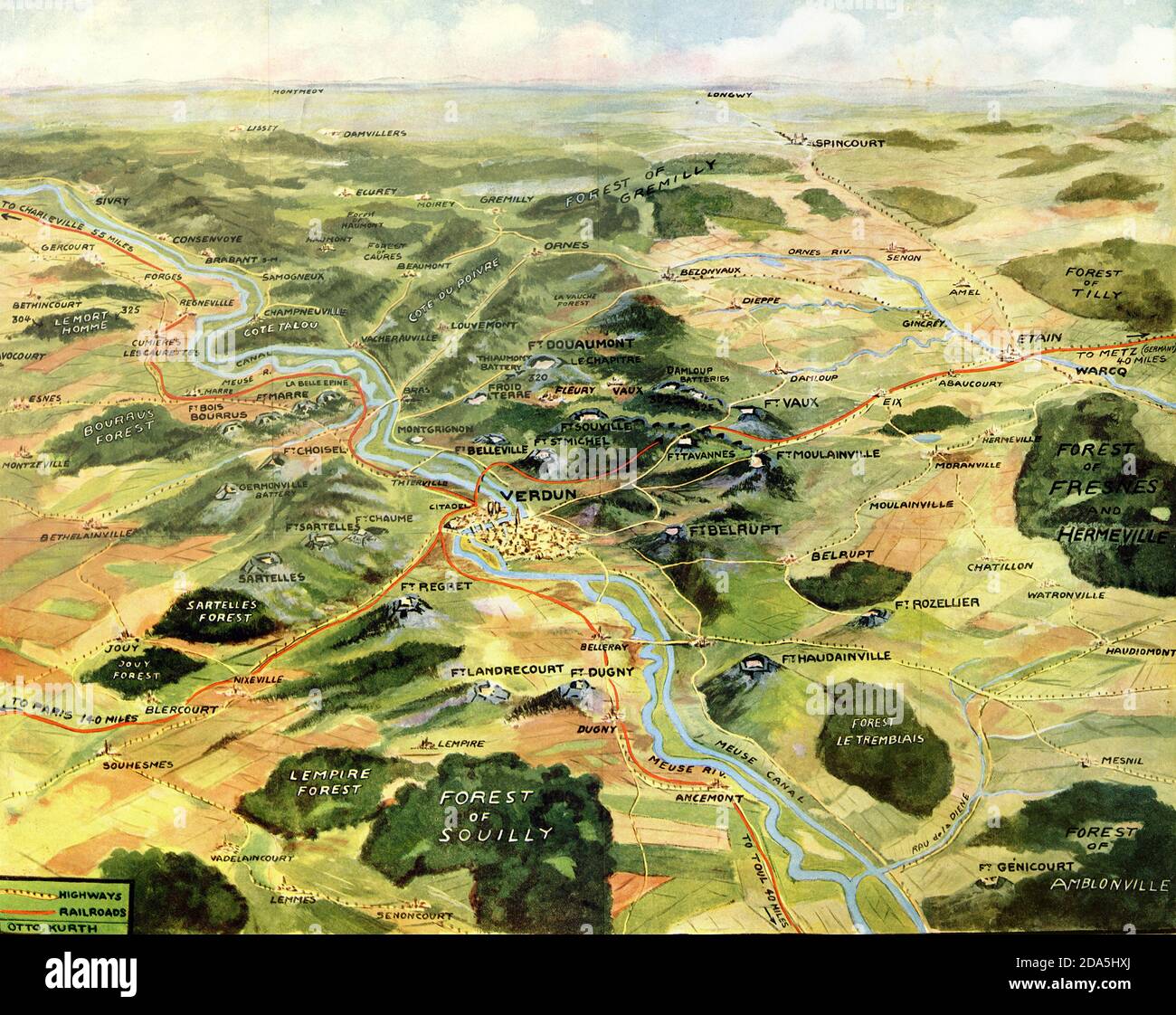

When you pull up a detailed Battle of Verdun map, the first thing that jumps out is the "Rive Droite" and "Rive Gauche"—the Right and Left banks of the Meuse. Most people focus on the Right Bank because that’s where the big names are. Douaumont. Vaux. Thiaumont. These weren't just names on a piece of paper; they were concrete behemoths that were supposed to be indestructible.

But here is the kicker: the French had actually partially disarmed these forts before the battle started. They thought permanent fortifications were obsolete after seeing what happened in Belgium. Huge mistake. When the Germans launched Operation Gericht on February 21, 1916, the French were caught with their pants down. The map shows the German line bulging inward, pushing toward the city of Verdun, creating a salient that was basically a giant target for artillery from three different sides.

The elevation matters too. You can't understand the Battle of Verdun map without looking at the contour lines. Height 304 and Le Mort Homme (Dead Man’s Hill) on the Left Bank were absolute slaughterhouses. Why? Because if the Germans held those hills, they could see everything. They could direct their artillery with terrifying precision. For months, the two sides traded these hills back and forth. By the time the fighting stopped, the peaks of these hills were actually several meters lower than when the war started. The mountains were literally ground into dust by millions of shells.

The Right Bank and the Fall of Fort Douaumont

Fort Douaumont is the anchor of any Battle of Verdun map. It was the highest and most powerful fort in the ring protecting the city. On February 25, a tiny group of German soldiers basically walked into the fort and took it without a serious fight. It was a national catastrophe for France.

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Lockport NY: Why Today’s Snow Isn’t Just Hype

If you look at the troop movements on a tactical map from that week, you see a total collapse of the French front line. It was chaos. General Philippe Pétain was called in to save the day, and his first move was to look at the map and realize there was only one way in and out: a narrow secondary road from Bar-le-Duc.

The Voie Sacrée: The Artery on the Map

Every Battle of Verdun map should have a thick, bold line running south. This was the Voie Sacrée, or the Sacred Way. Since the Germans controlled the main railways, Pétain had to rely on trucks. It’s hard to wrap your head around the scale. We’re talking about 3,500 trucks moving constantly, 24 hours a day. If a truck broke down, they didn't fix it. They pushed it into the ditch. You kept moving or you died.

This road is what kept the French army alive. Without it, the map would have folded in weeks. It’s a rare example of a logistical route being just as famous as the battlefield itself. While the infantry was dying in the mud at Fleury—a village that was captured and recaptured 16 times—the trucks were the heartbeat of the resistance.

The Zones of Death: Villages that Vanished

One of the most haunting things about a modern Battle of Verdun map is the "Zone Rouge" (Red Zone). There are nine villages on the map that simply don't exist anymore. They were destroyed so completely that they were never rebuilt.

- Beaumont-en-Verdunois

- Bezonvaux

- Cumières

- Douaumont (the village, not the fort)

- Fleury-devant-Douaumont

- Haumont-près-Samogneux

- Louvemont-Côte-du-Poivre

- Ornes

- Vaux-devant-Damloup

If you hike there today, the map shows streets, but the ground shows only craters. It's ghostly. The French government decided the soil was too saturated with unexploded ordnance and human remains to ever allow people to live there again. Even now, over a century later, the "Iron Harvest" continues. Farmers and foresters still find live shells every single year.

👉 See also: Economics Related News Articles: What the 2026 Headlines Actually Mean for Your Wallet

Why the Topography Favored the Germans (Until it Didn't)

Falkenhayn’s plan was cold. It was mathematical. He chose Verdun because the French would be forced to defend it for political reasons, but the geography favored German artillery. On a Battle of Verdun map, you can see the German railheads were much closer to the front than the French ones. This meant they could sustain a rate of fire that the world had never seen.

They called it Trommelfeuer—drumfire. It wasn't individual explosions; it was a continuous wall of noise.

But the map also shows why the Germans eventually failed. By pushing into the French lines, they created a narrow pocket. As they moved forward, they became vulnerable to French artillery firing from the flanks across the river. They got stuck in the very meat grinder they built. By June and July, the German casualties were nearly as high as the French. The "bleed them white" strategy was bleeding both sides to death.

The Turning Point in the Maps of Late 1916

By the time the Battle of the Somme started in July 1916, the pressure on Verdun finally eased. The Germans had to move troops away. If you compare a Battle of Verdun map from June to one from December, you’ll see the French "counter-offensive" lines. Under General Charles Mangin (nicknamed "The Butcher"), the French started clawing back the ground they had lost.

They used a "creeping barrage." This required insane coordination. The infantry would advance right behind a moving wall of their own artillery fire. If you moved too fast, you died by your own guns. If you moved too slow, the Germans would come out of their bunkers and mow you down. By December, the French had retaken Douaumont and Vaux. The map looked almost exactly like it did in February.

✨ Don't miss: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

Ten months. Hundreds of thousands dead. No territorial gain.

How to Read a Verdun Map for Historical Context

When you’re looking at these maps, don't just look at the lines. Look at the symbols for the "Ouvrages" (smaller fortifications) and the "Abris" (shelters). These were the only places men could hide from the shelling.

Basically, the battle was a series of tiny, disconnected wars fought for 50 yards of mud. A map makes it look organized. It wasn't. It was men living in shell holes filled with green water and the remains of their friends.

Practical Advice for Researchers and Travelers

If you are actually planning to visit or are doing deep-dive research into the Battle of Verdun map, keep these points in mind:

- Use IGN Maps: If you're visiting, get the French IGN (Institut Géographique National) maps. The 1:25,000 scale shows the trench remains that are still visible in the forests.

- The Ossuary is the Center: On any modern map, the Douaumont Ossuary is your landmark. It contains the remains of 130,000 unidentified soldiers. It sits right in the heart of the most contested ground.

- Watch the "Red Zone" Restrictions: Don't just wander off-trail because the map shows an old path. There is still a massive amount of unexploded chemical shells (arsenic and gas) in the ground.

- Compare 1914 vs 1916: To really understand the impact, compare a pre-war topographic map with a post-1916 trench map. The change in the actual shape of the hills is the most chilling part of the evidence.

Verdun wasn't a battle of maneuver. It was a battle of endurance. The Battle of Verdun map is a record of how much pain a civilization can tolerate before it snaps. Even today, the scars are so deep that you can see the trench lines from satellite imagery on Google Maps. The earth remembers, even if we sometimes forget the details.

To get the most out of your study, try to find a "layered" map that shows the progression of the front line month-by-month. It’s the only way to see the slow, agonizing pulse of the conflict. You’ll see the line move a kilometer forward over three months, then a kilometer back in three days. It’s a sobering reminder that in the Great War, "victory" was often just a return to the starting line.

Next Steps for Your Research

Start by cross-referencing the Battle of Verdun map with the personal accounts found in the diaries of soldiers like Henri Barbusse or the letters of German soldiers collected in "The German Student's War Letters." Seeing the names of the ravines—like the "Ravine of Death"—on a map while reading what happened there transforms a piece of paper into a tragic, living document. You can also use the digital archives at the Mémorial de Verdun website to overlay historical trench maps onto modern satellite views to see exactly where the front lines sat in relation to the current museums and monuments.