Honestly, it is a bit wild how little most of us actually know about the anatomy of the vagina. We live in an era of instant information, yet if you asked ten random people to point out the difference between the vagina and the vulva, at least seven would probably get it wrong. It’s not their fault. Education systems have been notoriously shy about this stuff for decades, often lumping everything "down there" into one vague, slightly taboo category.

But here is the thing.

Precision matters. When you understand how this specific part of the body is built—its muscles, its pH balance, its incredible ability to expand and snap back—you stop treating it like a mystery and start treating it like the sophisticated biological marvel it is.

The Vulva is Not the Vagina (Seriously)

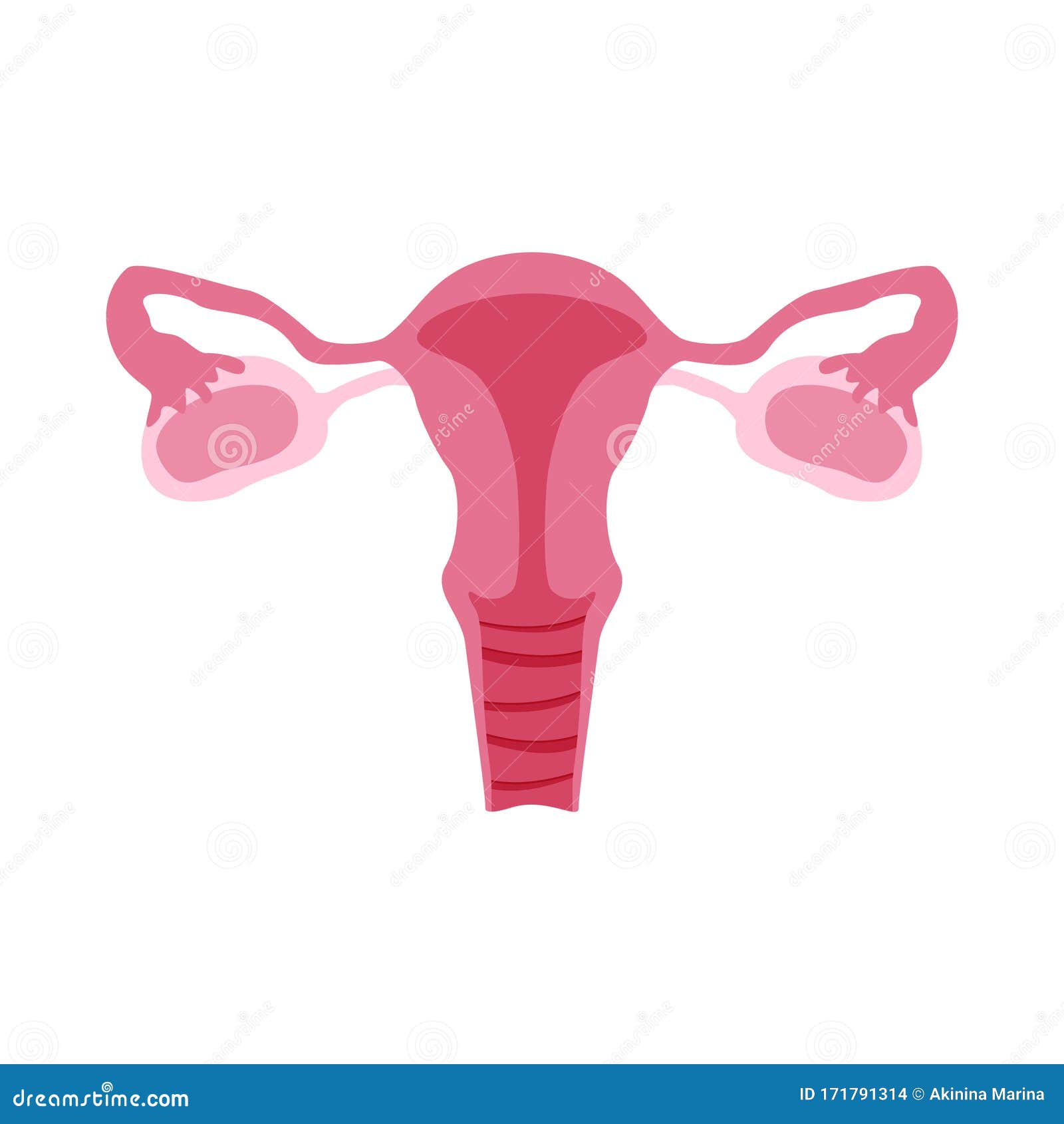

Let’s clear the air immediately. What you see on the outside? That’s the vulva. The anatomy of the vagina refers specifically to the internal canal. It’s the muscular tube that connects the vulva to the cervix. If the vulva is the front door and the porch, the vagina is the hallway leading into the rest of the house.

The vagina is roughly three to six inches long. That sounds short, right? But it’s incredibly stretchy. Think of it like an accordion or a pleated skirt. These folds are called rugae. When they aren’t being "used"—say, during intercourse or childbirth—the walls actually touch each other. There isn't just a giant, hollow cavern sitting there. It’s a potential space, meaning it expands only when something is inside it.

The Layers You Can't See

It isn't just a simple skin tube. It has layers. The inner lining is a mucous membrane, similar to the inside of your cheek. Beneath that is a layer of smooth muscle, and then a layer of connective tissue that tethers it to the rest of the pelvic structure. This layering is why the vagina is so resilient.

Dr. Jen Gunter, a board-certified OB/GYN and author of The Vagina Bible, often points out that the vagina is a self-cleaning oven. This isn't just a catchy metaphor. The vaginal flora, specifically Lactobacillus bacteria, produce lactic acid. This keeps the pH level around 3.5 to 4.5. That’s acidic. It’s meant to be that way to keep "bad" bacteria from moving in and setting up shop.

✨ Don't miss: Why Meditation for Emotional Numbness is Harder (and Better) Than You Think

The Pelvic Floor: The Unsung Support System

You can't talk about the anatomy of the vagina without mentioning the pelvic floor. Imagine a muscular hammock. This hammock holds up your bladder, your uterus, and your rectum. The vagina passes right through the middle of it.

When people talk about "tightness" or "looseness," they are usually talking about the tone of these pelvic floor muscles, not the vaginal canal itself. If those muscles are too tight (hypertonic), it can make things like tampon insertion or sex incredibly painful. If they are too weak, you might experience prolapse or stress incontinence—that annoying leak when you sneeze.

- The Pubococcygeus (PC) Muscle: This is the big one. It’s the main muscle involved in those Kegel exercises everyone talks about.

- The Levator Ani: This is actually a group of muscles that support the pelvic viscera.

It’s a complex web. If one part of the web is out of sync, the whole system feels it.

The G-Spot and the Fornices

Is the G-spot real?

Biologically, it’s not a distinct "organ" like a kidney. Most researchers, including those who published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine, suggest it’s more of an extension of the clitoral network. When you stimulate the anterior (front) wall of the vagina, you’re actually pressing against the internal "roots" of the clitoris and the urethral sponge.

Then there are the vaginal fornices. These are the little pockets or recesses at the very top of the vaginal canal, surrounding the cervix. They serve a functional purpose during reproduction by acting as a "well" for semen, but they also contribute to the sensations of fullness during physical intimacy.

🔗 Read more: Images of Grief and Loss: Why We Look When It Hurts

A Note on Variation

No two vaginas look or feel exactly the same. Depth varies. The shape of the rugae varies. The way the cervix tilts—whether it's anteverted (forward) or retroverted (tilted back)—changes the angle of the vaginal canal entirely. Around 20% of women have a retroverted uterus, which is just a normal anatomical variation, like being left-handed.

The Microbiome: A Living Ecosystem

This is where the anatomy of the vagina gets really high-tech. It isn't just tissue; it's a biome.

When estrogen levels are high, the vaginal lining thickens and produces glycogen. The Lactobacillus we mentioned earlier eat that glycogen and turn it into lactic acid. This is a beautiful, symbiotic relationship. However, things like hormonal birth control, menopause, or even high-stress levels can drop those estrogen levels. When that happens, the lining gets thinner (atrophy) and the pH can rise, leading to infections like BV (Bacterial Vaginosis) or yeast overgrowth.

It is a delicate balance.

Scented soaps? Douches? They are the enemies of this ecosystem. They strip away the protective mucus and kill the good bacteria. Honestly, water is usually all you need for the external bits, and the internal bits take care of themselves.

Myths That Just Won't Die

We need to address the "stretched out" myth. It is biologically impossible for the vagina to be "stretched out" permanently by sex. It’s a muscle. Think about it: a baby—which is roughly the size of a watermelon—can pass through the vaginal canal, and the tissue heals and returns to nearly its original state within months. A penis or a toy isn't going to change the structural integrity of those muscle fibers.

💡 You might also like: Why the Ginger and Lemon Shot Actually Works (And Why It Might Not)

What does change the feeling of the anatomy of the vagina over time is age and hormones. As we hit menopause, the drop in estrogen leads to "vaginal atrophy." The walls become thinner, less elastic, and drier. This isn't a permanent "stretching," but a change in the tissue quality itself.

Why the Hymen is Misunderstood

The hymen is not a "seal." If it were, how would period blood get out? It’s more like a thin, stretchy fringe of tissue around the vaginal opening. Some people are born with very little hymenal tissue, others have more. It can wear away through sports, tampon use, or just general activity. The idea that it "pops" or "breaks" is mostly a cultural myth rather than a medical reality.

Practical Steps for Pelvic Health

Knowing the anatomy of the vagina is only half the battle. You have to use that knowledge.

- Get to know your "normal." Use a mirror. Seriously. Understanding what your vulva looks like and how the vaginal opening appears helps you spot changes like redness, unusual discharge, or new bumps early on.

- Breathe into your pelvic floor. Most people hold tension in their pelvic floor without realizing it. Practice "reverse Kegels"—basically, the feeling of consciously relaxing those muscles as if you're trying to let them drop toward the floor.

- Check your pH triggers. If you find yourself getting frequent infections, look at your triggers. Tight synthetic underwear, sugar-heavy diets, or certain lubricants can all throw off the acidity.

- Lube is your friend. Especially as you age or if you're on certain medications. Friction can cause micro-tears in the vaginal lining, which are uncomfortable and provide an entry point for bacteria.

- See a Pelvic Floor Physical Therapist. If you have pain, leaking, or just feel "off," these specialists are the gold standard. They don't just look at the vagina; they look at the hips, the breath, and the entire muscular structure supporting your core.

The vagina is not a passive tube. It is a dynamic, reactive, and self-regulating environment. When you stop viewing it through the lens of mystery or shame and start seeing the actual biological complexity of the anatomy of the vagina, you're much better equipped to advocate for your own health.

Knowledge here isn't just "good to have." It's foundational.

What to Do Next

Start by tracking your cycle and any accompanying changes in vaginal discharge. This discharge—cervical mucus—changes consistency based on your hormones and is a direct reflection of what's happening in your internal anatomy. If you experience persistent pain during intercourse or chronic itching that doesn't resolve with standard over-the-counter treatments, skip the "home remedies" and book an appointment with a gynecologist. Be specific about where the discomfort is: is it at the opening (the vestibule) or deeper inside? This distinction helps your doctor determine if the issue is skin-related, muscular, or hormonal. Lastly, prioritize cotton or breathable fabrics to allow the microbiome to stay balanced and dry.