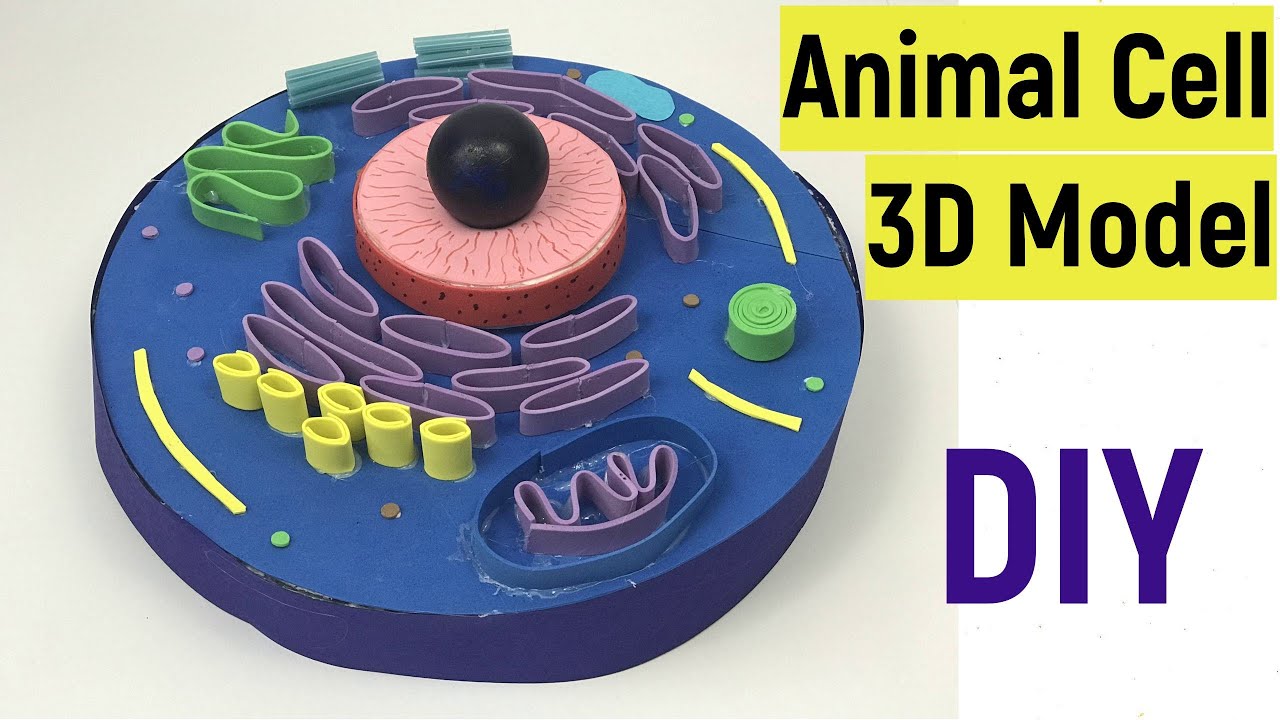

If you close your eyes and think of an animal cell, you probably see a fried egg. A flat, purple yolk sitting in some clear egg white. That's the fault of every middle school biology poster ever printed. But here is the thing: cells don't live in 2D. They are cramped, chaotic, three-dimensional machines. Honestly, the 3D of animal cell architecture is more like a crowded New York City subway car than a calm pond. It’s packed. It's moving. And everything is touching everything else.

The physical reality of the 3D of animal cell space

We need to talk about volume. When we look at a slide under a microscope, we’re looking at a slice. It’s like taking a single frame of a movie and trying to guess the whole plot. In a real, living 3D environment, the cytoplasm isn't just "watery goo." It’s a dense gel. Imagine trying to run through a swimming pool filled with maple syrup and yarn. That’s what a protein feels like trying to get from the nucleus to the cell membrane.

The 3D of animal cell layout is actually an engineering masterpiece. Scientists like Dr. Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute have used 3D super-resolution microscopy to show that organelles aren't just floating around randomly. They are tethered. They have "contact sites" where they literally hug each other to swap lipids and signals.

The Nucleus isn't just a ball

Most people think the nucleus is a solid sphere. Nope. It’s more like a crumpled-up paper bag with a double-layered skin. In a 3D space, this "bag" is perforated with thousands of nuclear pores. Think of them as high-security gates. Because the cell is a 3D object, these pores are distributed all around the surface, not just on the "edges" we see in drawings. This allows the nucleus to receive signals from any direction in the three-dimensional cytosol.

The Endoplasmic Reticulum is a 3D labyrinth

If the nucleus is the brain, the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) is the factory floor. But it’s not just a few squiggly lines. In a 3D model, the ER is a massive, interconnected network of sheets and tubes that can take up more than 10% of the entire cell's volume.

- It wraps around the nucleus like a blanket.

- It stretches out to the very edges of the cell membrane.

- It forms "tubular matrices" that look like a messy pile of garden hoses.

Researchers using Focused Ion Beam Scanning Electron Microscopy (FIB-SEM) have mapped these structures in 3D, revealing that the ER is constantly reshaping itself. It's dynamic. One minute it's a flat sheet (cisternae), and the next, it's a network of tubes. This 3D flexibility is why your cells can react so fast to stress or a need for more proteins.

Mitochondria are not beans

This is the biggest lie in biology. "The powerhouse of the cell" is usually drawn as a little orange bean with a zigzag inside. In reality, in the 3D of animal cell environment, mitochondria often exist as a massive, branching network. It's called a mitochondrial reticulum.

💡 You might also like: Tesla Cybertruck Off Road: What Most People Get Wrong

Imagine a ginger root that keeps growing and fusing with other ginger roots. That’s what’s happening inside your muscles right now. These 3D networks allow the cell to share energy across long distances. If one part of the network is healthy and another is struggling, the 3D connection lets them balance out the load. It’s basically a biological power grid.

Why the 3D shape actually matters for your health

Structure equals function. It’s a cliché because it’s true. When the 3D geometry of a cell gets wonky, things go south fast. Take cancer, for example. One of the first things a pathologist looks for is a change in the 3D shape of the nucleus. If it’s not the right "roundness," that’s a red flag.

In neurodegenerative diseases like ALS or Alzheimer’s, the 3D transport system breaks down. The "tracks" (microtubules) that move cargo across the 3D space of a long neuron get tangled. It’s a 3D traffic jam that eventually kills the cell.

The Cytoskeleton: The 3D scaffolding

How does a cell keep its shape if it’s just a bag of gel? The cytoskeleton.

You’ve got three main components:

- Microfilaments (the thin ones)

- Intermediate filaments (the tough ones)

- Microtubules (the highways)

These aren't just structural beams. They are more like a 3D spiderweb that is constantly being built and torn down. When a white blood cell "crawls" toward a bacteria, it's rapidly assembling these 3D fibers in the front and dissolving them in the back. It's literally 3D printing its own legs as it moves.

Visualizing the 3D of animal cell today

We’ve moved past the era of just guessing. Technologies like Cryo-Electron Tomography (Cryo-ET) allow us to freeze a cell so fast that the water doesn't even form ice crystals. This "vitrifies" the cell, catching it in a native 3D state.

📖 Related: Cost of Replacing MacBook Pro Battery: What Most People Get Wrong

When we look at these images, we see things we never expected. We see how ribosomes—the protein builders—are crowded together like spectators at a stadium. We see how the Golgi apparatus is shaped like a stack of pita bread, but with tiny bubbles (vesicles) constantly budding off the sides in every direction.

It's messy. It's beautiful.

What we get wrong about the "empty" space

There is no empty space. In a 2D drawing, the "white space" is just background. In the 3D of animal cell reality, that space is filled with the "interactome." Thousands of different proteins are bumping into each other millions of times per second.

- Diffusion: Small molecules zip around via brownian motion.

- Active Transport: Motor proteins like kinesin literally "walk" along 3D microtubule tracks carrying huge sacs of chemicals.

- Crowding: The concentration of molecules is so high that it actually changes how chemical reactions happen.

This 3D crowding is actually helpful. It forces molecules that need to interact to stay close together. It’s like being in a crowded elevator; you’re much more likely to bump into the person next to you than if you were in an empty football field.

Practical ways to use this knowledge

If you’re a student, a researcher, or just a science nerd, stop looking at 2D posters. If you want to actually understand how life works, you have to think in volumes.

- Use VR and AR tools: There are now apps like "CellWorld" or VR simulations that let you walk through a 3D model of a cell. Doing this for ten minutes will teach you more than ten hours of reading a textbook.

- Look for FIB-SEM data: Search for "FIB-SEM cell reconstructions" on YouTube. Seeing a cell sliced layer by layer and then reconstructed in 3D is a religious experience for your brain.

- Think about density: Next time you hear about a "chemical reaction" in a cell, don't picture two dots hitting each other. Picture a crowded 3D room where everyone is shaking hands.

The 3D of animal cell isn't just a fun way to draw things; it is the fundamental constraint of life. Every hormone your body releases, every thought you have, and every muscle contraction depends on the fact that these organelles are positioned perfectly in three-dimensional space. We are 3D creatures made of 3D machines. It’s time we started looking at them that way.

To dive deeper, look into the "Human Protein Atlas" which has been working on mapping where every protein lives in the 3D landscape of different cell types. It’s the closest thing we have to a Google Maps for the microscopic world. Check out their "Cell Section" to see actual 3D localized data that moves beyond the "fried egg" myth.