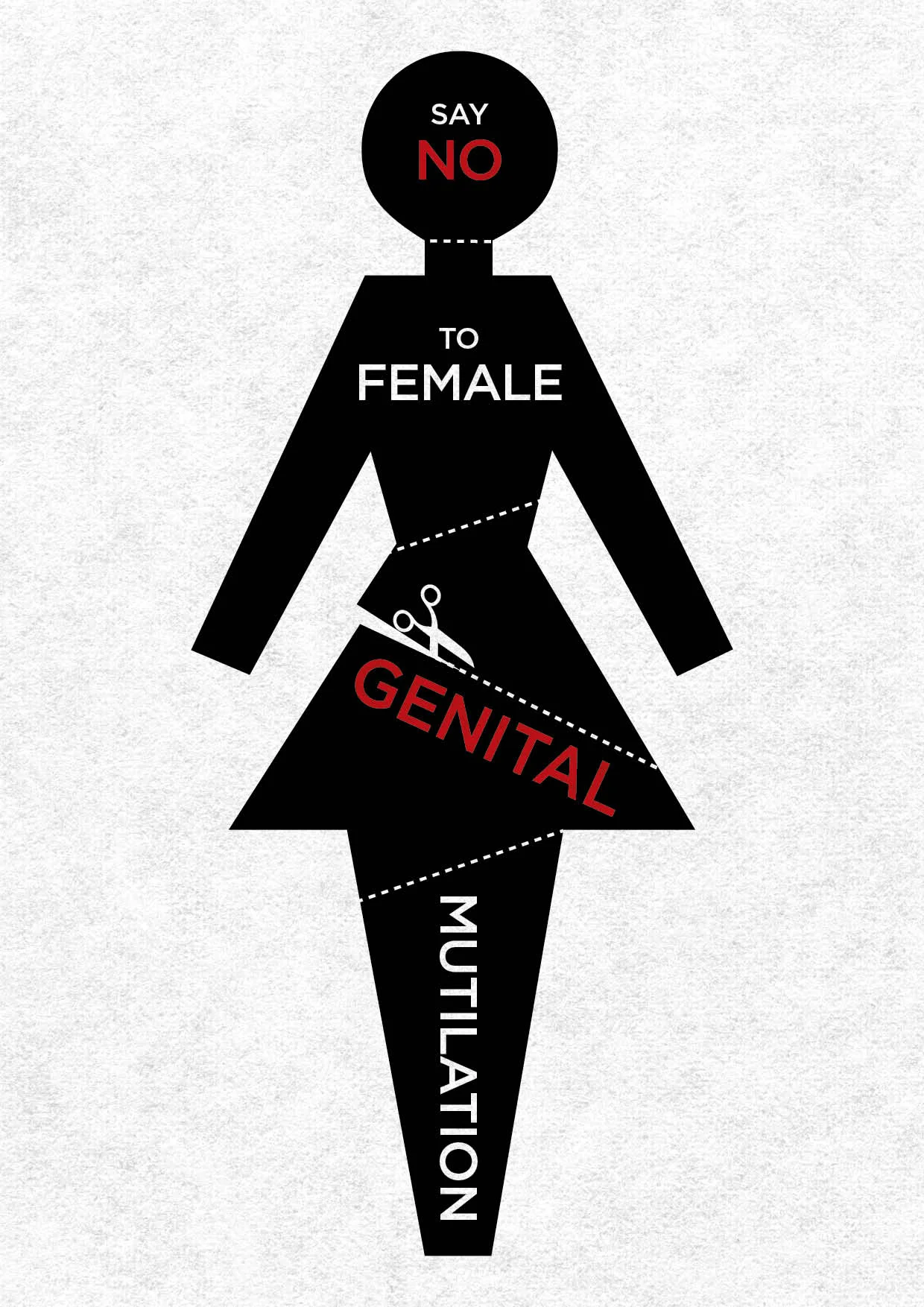

It is a difficult subject. Most people look away the second they hear the acronym, but we need to talk about what is the FGM and why it hasn't disappeared despite decades of international outcry. Female Genital Mutilation isn't just a "cultural practice" found in a textbook. It is a lived reality for over 200 million women and girls alive today. Honestly, the numbers are staggering. We are talking about a procedure that involves the partial or total removal of external female genitalia for non-medical reasons. No health benefits. Zero. Just a lifetime of potential complications.

You've probably heard it called "female circumcision," but that term is pretty misleading. It suggests an equivalence to male circumcision, which isn't medically or anatomically accurate. FGM is more about control—social, sexual, and communal. It’s usually performed on young girls between infancy and age 15. The trauma isn't just physical; it's a deep-seated psychological scar that many carry into adulthood without ever having a name for it.

The Four Types Defined by the WHO

The World Health Organization (WHO) doesn't mince words here. They’ve categorized this into four distinct types to help medical professionals and activists understand the severity of what they're looking at.

Type 1 is often called a clitoridectomy. This is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans. Sometimes it's just the prepuce—the fold of skin surrounding the clitoral glans. Type 2 goes further. Known as excision, it involves the removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora, sometimes with the labia majora.

Then there is Type 3, which is particularly harrowing. It's called infibulation. This involves narrowing the vaginal opening by creating a seal. The tissue is cut and repositioned, often stitched, leaving only a tiny opening for urine and menstrual blood. Imagine the daily pain. Type 4 is a "catch-all" category. It includes all other harmful procedures like pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, or cauterizing the genital area. It’s all categorized under what is the FGM because the intent is the same: a non-medical alteration of a girl's body.

🔗 Read more: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

Why Does This Keep Happening?

It’s easy to sit back and judge from a distance, but the sociology behind it is complex. In many communities, FGM is a prerequisite for marriage. If you aren't "cut," you aren't considered clean or a "real woman." You might be ostracized. Your family might lose their standing. It’s a social convention that functions like a trap. Mothers often put their daughters through it because they want them to have a future, to be accepted. They see it as an act of love, however twisted that sounds to an outsider.

Religious justification is another layer, though it’s largely a myth. No major sacred text—not the Quran, not the Bible—mandates FGM. Yet, local religious leaders often weave it into the fabric of faith. It’s about purity. It’s about tempering "female desire." Basically, it’s a tool used to ensure premarital virginity and marital fidelity.

The Health Consequences are Real

Let’s get into the clinical side. Because these procedures are often done without anesthesia and in non-sterile environments—think kitchen knives, razor blades, or even shards of glass—the immediate risks are terrifying. We’re talking about severe pain, shock, hemorrhage, and infections like tetanus or HIV. Some girls don't survive the procedure itself.

The long-term effects are a slow-burning crisis.

💡 You might also like: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

- Chronic vaginal and pelvic infections.

- Kidney failure.

- Painful menstruation because the blood can't escape easily.

- Complications during childbirth that can lead to neonatal death.

In Type 3 cases, the seal has to be cut open to allow for intercourse and again for childbirth—a process called de-infibulation. Then, sometimes, they are sewn back up again (re-infibulation). It is a cycle of repeated trauma.

The "Medicalization" Trend

One of the most concerning shifts in recent years is the medicalization of FGM. This is where the procedure is performed by healthcare providers—nurses, midwives, or even doctors. People think it’s "safer" because it’s done in a clinic with a scalpel. But the WHO is very clear: medicalization does not make it okay. It still violates a woman's right to physical integrity. It still has no medical benefit. In countries like Egypt and Sudan, this trend is huge. It gives a veneer of legitimacy to a human rights violation.

Where is FGM Most Prevalent?

While it's most common in 30 countries across western, eastern, and north-eastern Africa, it's not just an "African problem." It happens in parts of the Middle East, such as Yemen and Iraq, and in some Asian countries like Indonesia and Malaysia. Migration has also made it a global issue. You’ll find cases in the UK, the US, and across Europe. It’s often hidden. Girls might be taken "back home" during summer vacations for what is euphemistically called a "vacation cutting."

The Legal Battle and Global Progress

The tide is turning, albeit slowly. Many countries have passed specific laws banning FGM. In 2020, Sudan—a country with high prevalence—criminalized the practice, which was a massive milestone. But laws are only as good as their enforcement. If the community doesn't believe the law is right, they just move the practice underground.

📖 Related: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

Real change happens through community-led "collective abandonment." This is where an entire village decides together to stop. Organizations like Tostan in Senegal have had incredible success with this. They don't come in and lecture; they facilitate discussions about human rights and health. When the whole village agrees, there’s no social penalty for a girl who isn't cut. That’s the "aha" moment.

How Can We Help?

Awareness is the first step, but it’s not the last. Support organizations that work on the ground. These are the people providing safe houses for girls fleeing the "cutter" and educating grandmothers who are often the gatekeepers of the tradition.

If you are a healthcare professional, education is vital. Knowing how to identify the signs and how to provide culturally sensitive care to survivors can change a life. For the rest of us, it’s about keeping the conversation alive without stigmatizing the cultures involved. We have to separate the people from the practice.

Actionable Next Steps

If you want to be part of the solution, start with these concrete actions:

- Educate Yourself on Local Laws: If you live in a country with a diaspora community, learn the specific laws regarding FGM and "vacation cutting." Knowing the legal framework helps in advocacy.

- Support Survivors: Look for organizations like Desert Flower Foundation or Orchid Project. They focus on both prevention and helping women who live with the physical and mental scars of FGM.

- Engage in Informed Advocacy: Use your platform to share the reality of what is the FGM without resorting to "saviorism." Focus on the health facts and human rights.

- Watch for the Signs: In school or medical settings, be aware of girls who might be at risk, especially before long school breaks. Early intervention can prevent the procedure before it happens.

The goal isn't just to make FGM illegal; it's to make it unthinkable. It’s about a world where every girl can grow up with her body intact and her rights respected. It’s a long road, but the progress in the last decade proves that change is possible.