Honestly, it’s wild how much we don’t talk about the actual mechanics of the female human anatomy chest despite how much space it occupies in medical textbooks and, well, everyday life. You’d think by now everyone would have a clear handle on what’s going on under the surface. But ask the average person—or even many patients—to explain the difference between glandular tissue and Cooper’s ligaments, and you’ll mostly get blank stares. This isn't just about "breasts" in a surface-level sense. We are talking about a complex, multi-layered system of fat, connective tissue, nerves, and milk-producing machinery that responds to hormonal shifts with the precision of a Swiss watch.

Most people see the chest as a static feature. It isn't. It’s dynamic.

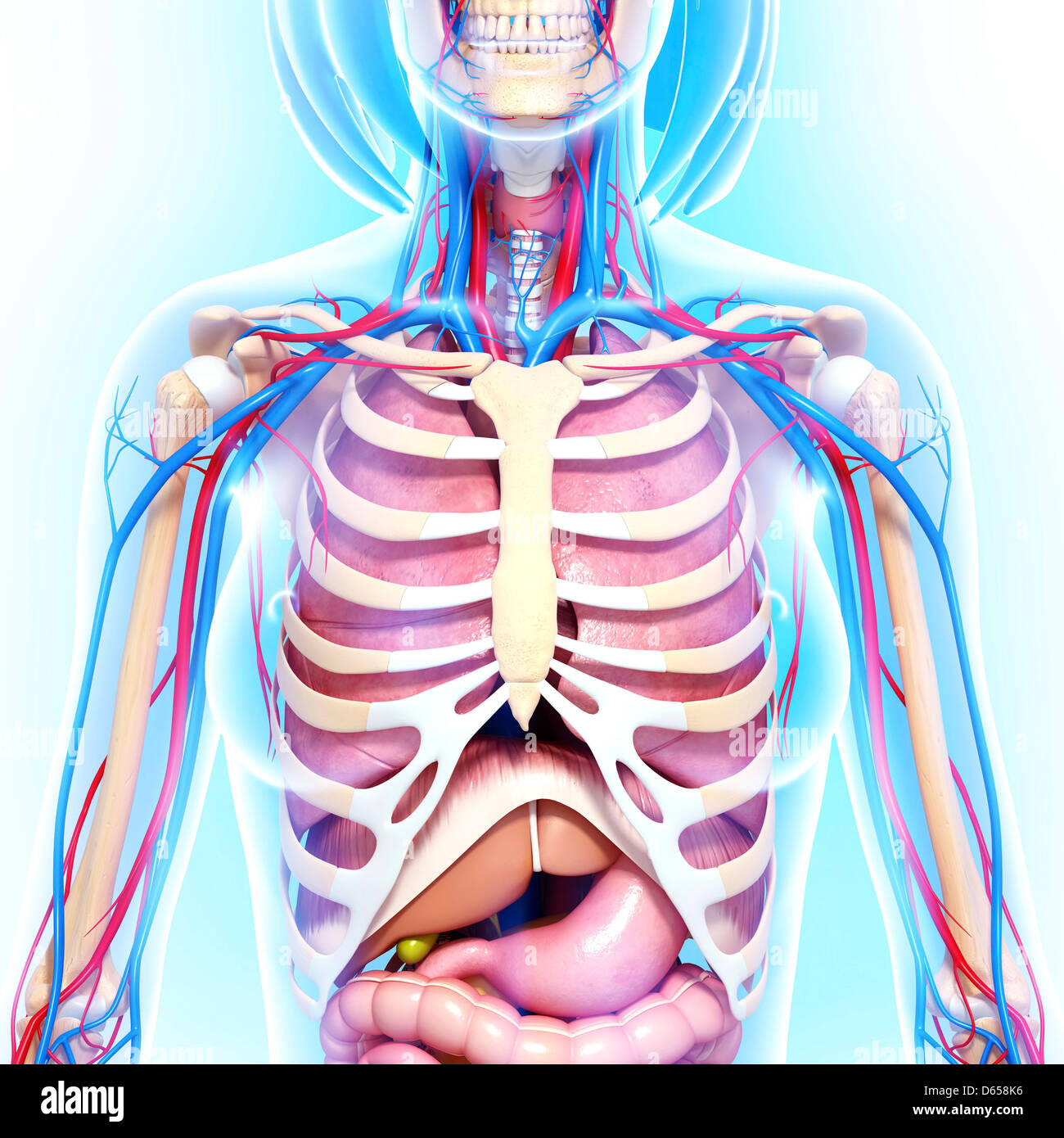

The female human anatomy chest is essentially a specialized sweat gland. That sounds weird, right? Evolutionarily speaking, mammary glands are modified apocrine glands. They are integrated into the thoracic wall, sitting right on top of the pectoralis major muscle. If you’ve ever felt a "pull" in your chest after a heavy workout, that’s because the connection between the breast tissue and the underlying muscle is incredibly tight. The anatomy isn't just "there"—it's anchored.

The Internal Map: More Than Just Fat

If you were to look at a cross-section, the first thing you'd notice is that the ratio of fat to functional tissue varies wildly from person to person. There is no "standard" percentage. Some women have high breast density, meaning they have more glandular and connective tissue than fat. This matters. According to the National Cancer Institute, high breast density can actually make mammograms harder to read because both dense tissue and tumors show up as white on the scan.

The structure is broken down into 15 to 20 lobes. These are the "leaves" of the tree. Inside these lobes are smaller lobules, which are the actual milk-producing bulbs. They all drain into lactiferous ducts. Think of these as a series of straws that lead to the nipple.

But wait. What keeps everything from just sagging instantly?

That would be the Cooper’s ligaments. These are thin, fascial bands that weave through the breast tissue and attach to the skin. They are the internal "bra" of the female human anatomy chest. When these stretch over time due to age, gravity, or high-impact movement without support, you get ptosis—the medical term for sagging. Once they stretch, they don't exactly snap back like a rubber band. This is why sports medicine experts like Dr. Joanna Wakefield-Scurr from the University of Portsmouth spend so much time researching breast biomechanics. The "bounce" isn't just vertical; it’s a figure-eight pattern.

The Nipple-Areola Complex: A Sensory Hub

The nipple and the surrounding pigmented skin, the areola, are packed with nerves. Specifically, the fourth intercostal nerve provides most of the sensation here. It’s a direct line to the brain.

You might have noticed tiny bumps on the areola. Those aren't pimples. They are Montgomery glands. Their job is to secrete a lipoid fluid that keeps the nipple lubricated and protected. They also produce a scent. Research suggests this scent helps newborns find the "target" for feeding. It’s a biological GPS system.

- The nipple itself contains smooth muscle fibers.

- When these fibers contract, the nipple becomes erect.

- This can happen due to cold, touch, or even just a sudden surge of oxytocin.

The color of the areola isn't fixed, either. It can darken significantly during pregnancy. This is often one of the first physical signs of hormonal shifts, driven by an increase in melanocyte-stimulating hormones. It’s the body quite literally changing its external map to prepare for a new biological function.

Hormones Are the Real Architects

You can't talk about female human anatomy chest structures without talking about estrogen and progesterone. They are the bosses. Every month, during the menstrual cycle, these hormones cause the milk ducts and glands to swell. This is why many people experience "cyclical mastalgia" or chest pain right before their period. The body is basically doing a "dry run" for pregnancy every single month.

During menopause, the process reverses. This is called involution.

📖 Related: Feeling Nausea When Eating: Why Your Stomach Actually Rebels at Mealtime

The glandular tissue starts to shrink, and the body replaces it with more fat. This is why the texture of the chest changes as women age. It becomes softer and less dense. It’s a total structural remodel. Understanding this shift is vital for self-exams because what felt "normal" at 25 will feel very different at 55.

Lymph Nodes: The Drainage System

This is the part people usually forget until they have a cold or a health scare. The axillary lymph nodes—located in the armpit area—drain about 75% of the lymph from the chest. This is the body’s filtration system. If there is an infection or an inflammatory process happening, these nodes might swell.

It's a common point of confusion. Sometimes a person feels a lump near their armpit and panics, but it's actually just a reactive lymph node doing its job because of a minor skin irritation or a systemic virus. However, because this is the primary drainage route, it’s also the first place doctors look when monitoring for more serious issues like cellular changes or oncology concerns.

Common Misconceptions About Symmetry and Size

Here is the truth: perfect symmetry is a myth.

Almost every human has one side that is slightly larger or shaped differently than the other. This is often linked to blood flow or even which hand is dominant, though the science on the "dominant hand" theory is still debated. Differences in size, known as breast asymmetry, are completely normal.

Also, size has zero correlation with the ability to produce milk. A person with a smaller chest can have just as many functional lobules as someone with a much larger chest. The difference in volume is almost entirely dictated by adipose (fat) tissue, not the "machinery" itself.

Why the Pectoral Muscle Matters

While the breast tissue itself doesn't contain muscle, it sits directly on the pectoralis major. This is a large, fan-shaped muscle. Strengthening this muscle won't change the size of the glandular tissue, but it provides a firmer "shelf" for the tissue to sit on. This is a common tip in fitness circles, but it's backed by basic musculoskeletal anatomy. If the foundation is strong, the overlying structures have better support.

Actionable Steps for Anatomy Awareness

Knowing the map is one thing; using it is another. Since the female human anatomy chest is so sensitive to hormonal and age-related changes, staying in tune with it requires a bit of consistency.

Get to know your "normal." Don't just look for lumps. Look for skin changes. Look for "dimpling" (which looks like the skin of an orange). This can indicate that something underneath is pulling on those Cooper's ligaments.

Track your cycle. If you notice pain or heaviness, check where you are in your month. If the pain disappears after your period starts, it’s likely just the standard hormonal ebb and flow. If it stays, that's when you call a professional.

Invest in a professional fitting. Since the Cooper’s ligaments are the only internal support, external support is crucial, especially during exercise. A 2020 study published in the Journal of Biomechanics showed that inadequate support leads to long-term tissue strain. Most people are wearing the wrong band size, which puts the weight on the shoulders rather than the ribcage where it belongs.

Check your lymph nodes. Next time you're in the shower, feel around the axillary area (the armpit). You're looking for anything that feels like a hard pea or a grape. Most of the time, it's nothing, but being aware of how your lymph nodes feel when you're healthy makes it much easier to spot when they're angry.

👉 See also: Natural Boobs and Tits: What Most People Get Wrong About Body Anatomy

Understanding this part of the body isn't just for doctors. It’s about taking ownership of your own biological reality. The more you know about the lobes, the ducts, and the ligaments, the less scary the inevitable changes feel. It’s a complex system, sure, but it’s one that’s been fine-tuned over millions of years of evolution to do exactly what it’s doing right now.