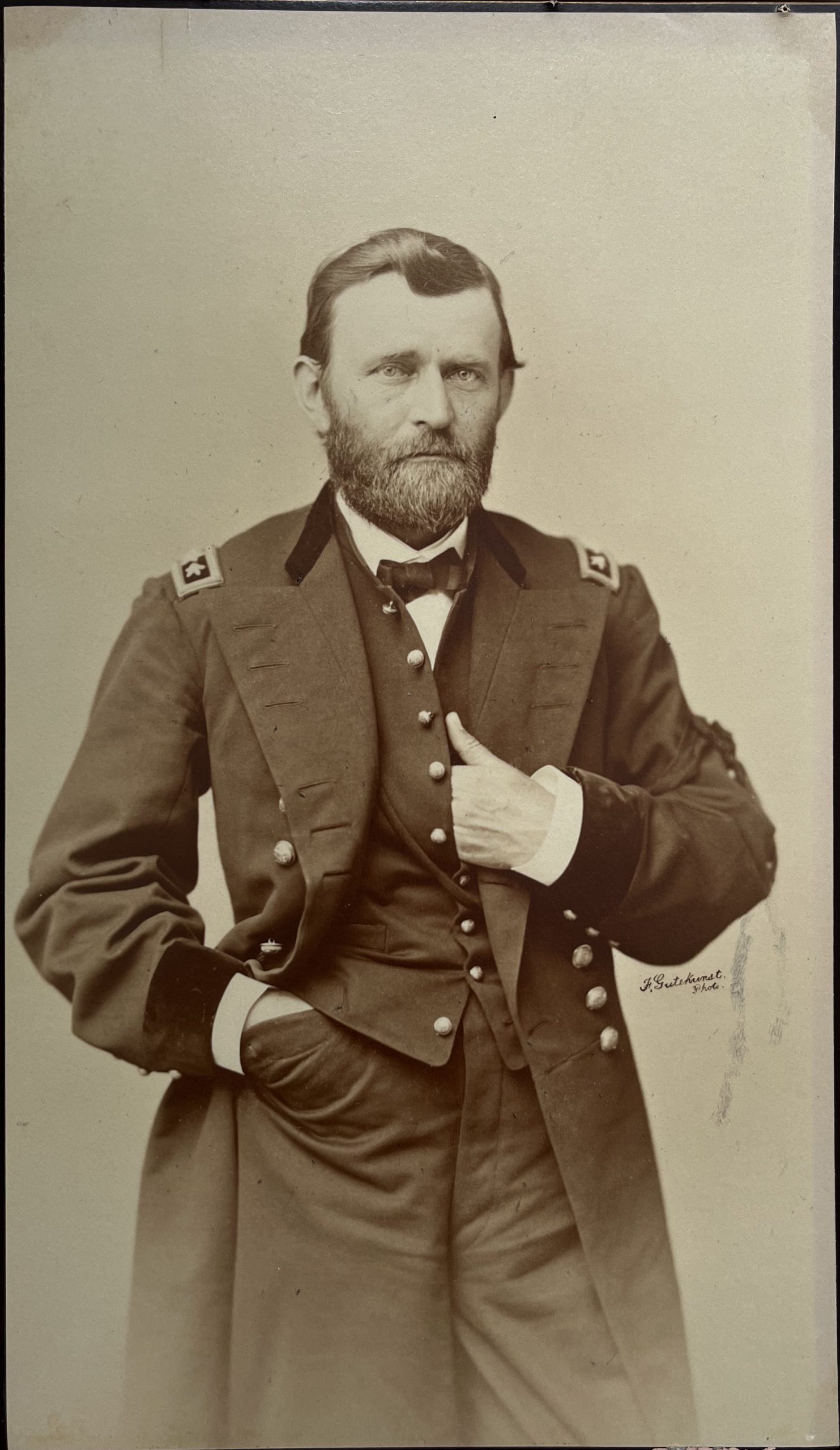

He was a failure. At least, that is what the history books tried to tell us for about a hundred years. If you went to school anytime between the 1920s and the 1990s, you probably learned that Ulysses S. Grant was a "butcher" who only won the Civil War because he had more men, and a president whose administration was so corrupt it barely deserves a footnote. It’s a convenient story. It’s also mostly wrong.

History is a messy business.

When you look at the actual life of Hiram Ulysses Grant—he only became "U.S. Grant" because of a clerical error at West Point—you find a man who was deeply sensitive, hated the sight of blood, and possessed a topological memory that allowed him to see entire battlefields in his head like a 3D map. He wasn't a drunkard stumbling into victory. He was a math whiz who realized, before almost anyone else, that the old way of fighting was dead.

The "Butcher" Myth and the Reality of 1864

Let’s talk about the blood. Critics, both then and now, point to the Overland Campaign—Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor—as proof of Grant’s callousness. They call him a butcher. Honestly, it’s a label that stuck because it’s easy to say, but it ignores the math of 19th-century warfare.

Robert E. Lee, the sainted general of the Lost Cause, actually lost a higher percentage of his men across the war than Grant did. Think about that for a second. Grant understood that the only way to end the slaughter was to move fast and never let up. If he stopped, the war dragged on. If the war dragged on, more people died in the long run.

It was a brutal, horrific logic.

At the Battle of the Wilderness, the woods literally caught fire. Men were pinned down in the brush while the world burned around them. In previous years, a Union general would have retreated after such a bloody stalemate. The soldiers expected it. They were used to losing. But when the columns reached the crossroads and Grant signaled them to turn south—further into Virginia, further toward the fight—the men started cheering. They realized they finally had a leader who wasn't afraid of the ghost of Robert E. Lee.

✨ Don't miss: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Ulysses S. Grant and the Struggle for Reconstruction

We usually stop the story at Appomattox. The grainy photos of the two generals in the parlor, the generous terms, the end of the rebellion. But Grant’s most difficult fight didn't happen on a horse. It happened in the White House.

When he took office in 1869, the country was a disaster. The Ku Klux Klan was effectively a domestic terrorist insurgency throughout the South. They were lynching Black voters, burning schools, and trying to undo everything the war had settled. Most people don't realize that Grant basically destroyed the first iteration of the KKK.

He didn't do it with speeches. He did it with the Department of Justice—which he created—and the suspension of habeas corpus in South Carolina. He sent federal troops to protect the rights of formerly enslaved people. For a few years in the 1870s, there were more Black men in Congress than there would be for the next century.

Why don't we hear about this?

Because the "Dunning School" of historians in the early 20th century decided that Reconstruction was a failure and that Grant was a puppet. They wanted to romanticize the South, and Grant—the man who actually tried to enforce the 15th Amendment—was an obstacle to that narrative. They focused on the scandals, like the Whiskey Ring or Crédit Mobilier.

Grant was definitely too trusting. He had a habit of believing that if a man served with him in the army, that man was honest. He was wrong. His cabinet was a revolving door of grifters and Civil War buddies who took advantage of his loyalty. But while his subordinates were stealing tax money, Grant was trying to prevent a second Civil War. He was trying to make sure the "new birth of freedom" Lincoln talked about actually meant something.

🔗 Read more: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

The Man Behind the Uniform

It’s weird to think about, but Grant was a failed leather goods salesman just years before he led the Union Army. He was living in Galena, Illinois, working for his father, a man he didn't particularly get along with. He was a guy who couldn't find his footing in civilian life.

He was also a devoted husband. His letters to his wife, Julia, are some of the most romantic, vulnerable pieces of writing from the era. He hated being away from her. When he was alone, he got depressed. That’s often when the rumors of his drinking cropped up—it was a coping mechanism for a man who was profoundly lonely and bored without his family or a clear mission.

And he loved horses. Like, really loved them. There’s a story from his time in the Mexican-American War where he performed a "circus trick" on a horse, jumping over obstacles that other riders wouldn't touch. He was the best horseman at West Point, yet he ended up in the infantry because there were no openings in the dragoons. Life is funny like that.

A Legacy Written in Pain

The end of his life is genuinely one of the most heroic things in American history. Grant was broke—scammed by a business partner in a Ponzi scheme—and dying of throat cancer. He was in constant, agonizing pain. He couldn't swallow. He could barely speak.

But he had to provide for Julia.

He sat on a porch in Mount McGregor, wrapped in blankets, and wrote his Personal Memoirs. He finished them just days before he died. Mark Twain, who published the book, called them the finest military memoirs since Caesar's Commentaries. They are lean, clear, and honest. They saved his family from poverty and remain a masterpiece of American literature.

💡 You might also like: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

If you want to understand the man, read his words. He doesn't brag. He doesn't make excuses. He just tells you what happened.

What We Can Learn from Grant Today

We live in a time where people love to tear down statues and debate legacies. Grant is a complicated figure for that. He owned a slave for a brief period—William Jones—whom he eventually set free rather than selling him for much-needed cash, even though Grant was struggling financially at the time. His policy toward Native Americans, the "Peace Policy," was well-intentioned but led to the disastrous attempt to "civilize" tribes and the eventual Battle of the Little Bighorn.

He wasn't perfect. Nobody is.

But he was a man who grew. He was a man who changed his mind. He went from a soldier who didn't care much for politics to a President who realized that the United States couldn't exist if it didn't protect all its citizens.

The Actionable Insight for Today:

If you want to truly understand this era, stop looking at history as a list of dates. Look at it as a series of character studies. To dive deeper into the real Ulysses S. Grant, start with these three steps:

- Read the Memoirs: Skip the biographies for a moment and go to the source. Grant’s Personal Memoirs are surprisingly readable and give you a direct window into his strategic mind.

- Visit the Sites: If you’re ever in New York City, go to Grant’s Tomb. It’s the largest mausoleum in North America. Why? Because when he died, the entire country—North and South—mourned him. It reminds you how much he meant to the people who actually lived through that time.

- Audit the Reconstruction Era: Look into the "Enforcement Acts" of 1870 and 1871. Seeing how Grant used the law to fight the KKK provides a much different perspective than the "corrupt drunk" trope found in older textbooks.

Grant’s life proves that you can fail at forty and still change the world at fifty. He teaches us that persistence—what he called "pegging away"—is often more important than flash or brilliance. He was the "Unconditional Surrender" general, but he was also the man who told the defeated Confederates to take their horses home for the spring planting. He knew when to fight, and he knew when to heal.

We’re finally starting to see him clearly. It’s about time.