You’re sitting in a cold exam room, and your doctor turns the monitor toward you. There it is. A grainy, pinkish-white crater on the screen that looks like a miniature volcano. Seeing ulcers in stomach images for the first time is honestly a bit jarring. It’s not just a "tummy ache" anymore; it’s a physical, visible hole in your lining.

Most people think of stomach ulcers as a result of "stress" or "too much spicy food." That’s a total myth. Well, mostly. While stress doesn't help, the reality of what we see during an endoscopy is usually the work of a tiny, corkscrew-shaped bacteria called Helicobacter pylori or the silent damage from over-the-counter painkillers.

The Visual Reality of Gastric Ulcers

When a gastroenterologist threads an endoscope down, they aren't just looking for "redness." They are hunting for specific architectural changes. In high-definition ulcers in stomach images, a "clean" ulcer often has a white or yellowish base. This isn't pus; it’s fibrin, a protein that helps with clotting. It’s basically your body trying to put a Band-Aid on itself from the inside out.

Sometimes, though, the images show something more concerning. A black spot in the middle of that white crater usually means there was a recent bleed. If the doctor sees a "visible vessel"—which looks like a tiny, pulsating red twig—that’s a medical red flag. It means the ulcer has eroded deep enough to hit a blood pipe. That’s when things get real.

The edges matter too. In a benign ulcer, the borders are usually smooth and regular. They look like a clean punch-out. If the edges look heaped up, ragged, or nodular, that’s when the word "biopsy" starts getting tossed around. Doctors have to rule out gastric cancer, which can sometimes masquerade as a standard ulcer in its early stages.

Why the Images Look Different Every Time

You might see one photo where the ulcer looks like a giant canyon and another where it's a tiny speck. Size is relative. Some "giant" ulcers are over 2 centimeters wide. These are often seen in patients who take a lot of NSAIDs (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) like ibuprofen or naproxen. These drugs basically shut down the stomach's "slime shield," allowing acid to eat the wall alive.

💡 You might also like: Why the Autism Age of Diagnosis is Still Moving So Slow

Then there’s the location. An ulcer in the "antrum" (the bottom of the stomach) looks different than one in the "fundus" (the top). The lighting from the endoscope can also play tricks. Modern scopes use something called NBI—Narrow Band Imaging. It flips the light spectrum to make blood vessels pop out in weird greens and blues. It looks like a sci-fi movie, but it helps doctors see if the tissue pattern is healthy or "disorganized," which is a fancy way of saying potentially precancerous.

The H. Pylori Factor

If your ulcers in stomach images show a lot of generalized redness (gastritis) around the hole, H. pylori is usually the culprit. This bacteria is a survivor. It produces an enzyme called urease that neutralizes stomach acid in its immediate vicinity, creating a little "safe zone" for it to burrow into your mucus.

Dr. Barry Marshall actually drank a beaker of this bacteria back in the 80s to prove it caused ulcers. He got sick, he got an ulcer, he cured himself with antibiotics, and eventually, he won a Nobel Prize. Total legend. Now, when we see that specific pattern of inflammation on a screen, we know exactly what we’re dealing with. It’s an infection, not just a lifestyle "choice."

What Happens After the Photo is Taken?

The image is just the starting point. It's a snapshot in time. The real work happens in the lab. Usually, the doctor will snip a tiny piece of the edge—don't worry, you're sedated and the stomach lining doesn't have "pain" nerves in the way your skin does—to check for that bacteria or abnormal cells.

Healing is actually pretty fast once the acid is turned off. If you look at ulcers in stomach images taken just eight weeks apart after a patient starts a Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI), the transformation is wild. That angry, white-based crater turns into a "red scar," then eventually a "white scar," and finally, it's almost invisible. The body wants to heal; you just have to stop the acid from sandblasting the wound every time you eat.

Misconceptions That Just Won't Die

We need to talk about the "Milk Myth." For decades, people thought drinking milk "coated" the stomach and helped ulcers. Honestly? It makes it worse. Milk is a rebel. It might feel cool going down, but the calcium and protein in milk actually trigger more acid production. You’re essentially throwing gasoline on the fire while trying to blow it out.

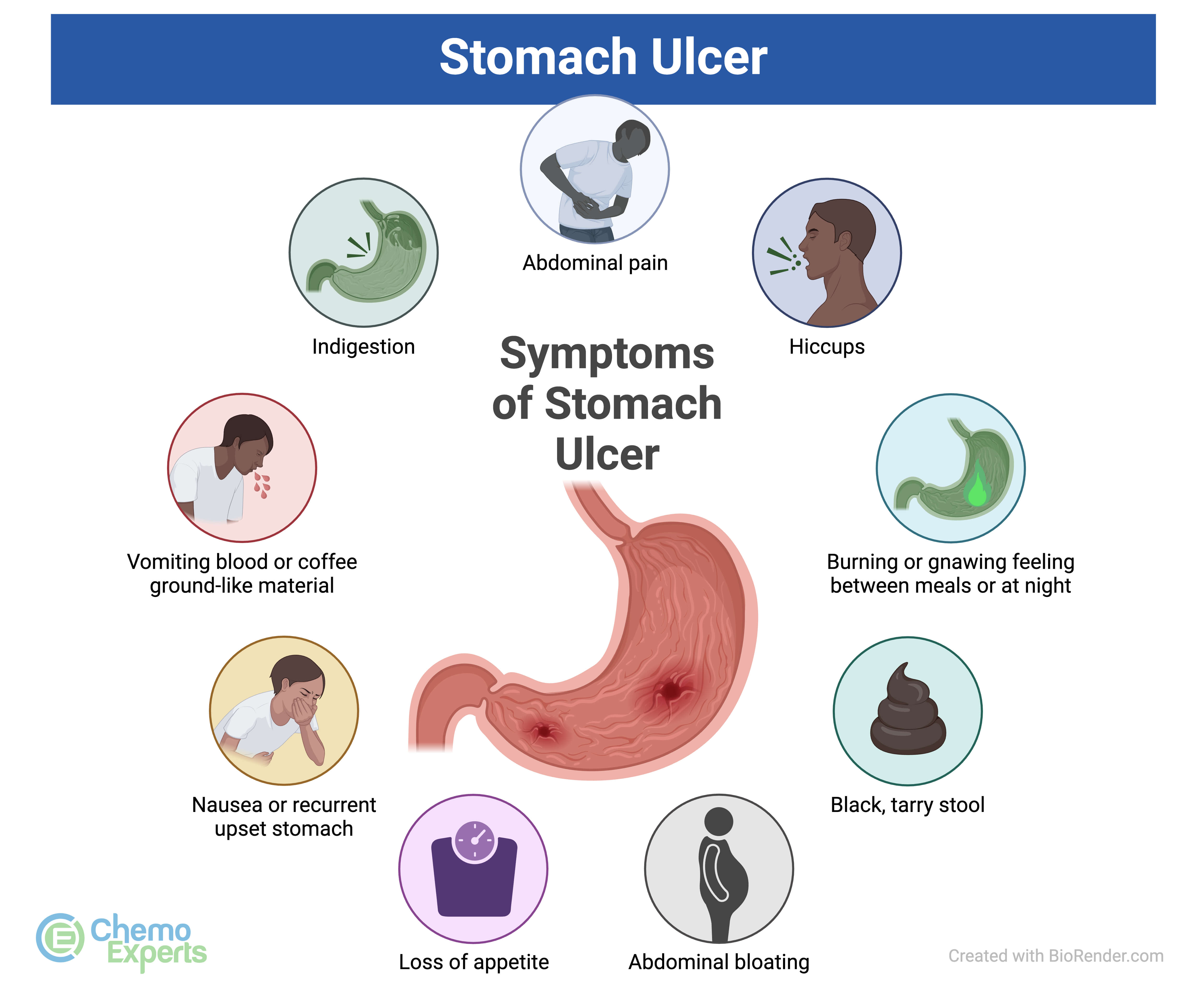

Another big one? "I don't feel pain, so I don't have an ulcer." Wrong. Many people—especially older adults or those on certain meds—have "silent" ulcers. The first sign isn't a burning stomach; it’s feeling incredibly tired because they’re slowly losing blood, or seeing "coffee ground" looking stuff in their vomit. If you wait for the pain, you might be waiting too long.

Practical Steps If You're Concerned

If you’ve seen your own ulcers in stomach images or suspect you have one, you can't just "wait it out."

🔗 Read more: Mass General Nurses Brain Tumor Clusters: What the Data Actually Says

First, look at your med cabinet. If you’re popping ibuprofen like candy for back pain or headaches, stop. Talk to your doctor about alternatives like acetaminophen, which doesn't eat your stomach lining.

Second, get tested for H. pylori. It’s a simple breath or stool test. You don't always need the "camera down the throat" if your symptoms are mild and you test positive for the bug; sometimes a round of antibiotics and acid-blockers does the trick.

Third, watch your "triggers," but don't obsess. If coffee makes your stomach burn, back off. But don't think that living on a diet of bland toast will "cure" a bacterial infection. It won't. You need medicine for that.

📖 Related: You Will Not Alone: Why Community Support Is Changing Health Care Outcomes

Finally, if you ever see black, tarry stools, go to the ER. That's not "something I ate." That is digested blood, and it means your ulcer is active and dangerous.

The goal isn't just to have "clean" ulcers in stomach images; it's to fix the environment that allowed the ulcer to form in the first place. Whether that’s killing off a bacterial invader or changing how you manage pain, the solution is usually much simpler than the scary-looking pictures suggest.