You're walking through a damp forest after a heavy rain and there it is. A pops of bright orange or a cluster of velvety white. It’s tempting to think you’ve just found dinner. But types of wild mushrooms are a tricky business. Honestly, most people get it wrong because they rely on "old wives' tales" or a blurry photo from a Facebook group. Nature doesn't care about your hunger or your curiosity. One bite can be the difference between a gourmet risotto and a trip to the emergency room—or worse.

Mushrooms aren't plants. They are the fruiting bodies of fungi, basically the "apples" of a massive underground tree called mycelium. While there are thousands of species globally, only a handful are truly delicious, many are "LBMs" (Little Brown Mushrooms) that all look the same, and a few are legitimately deadly.

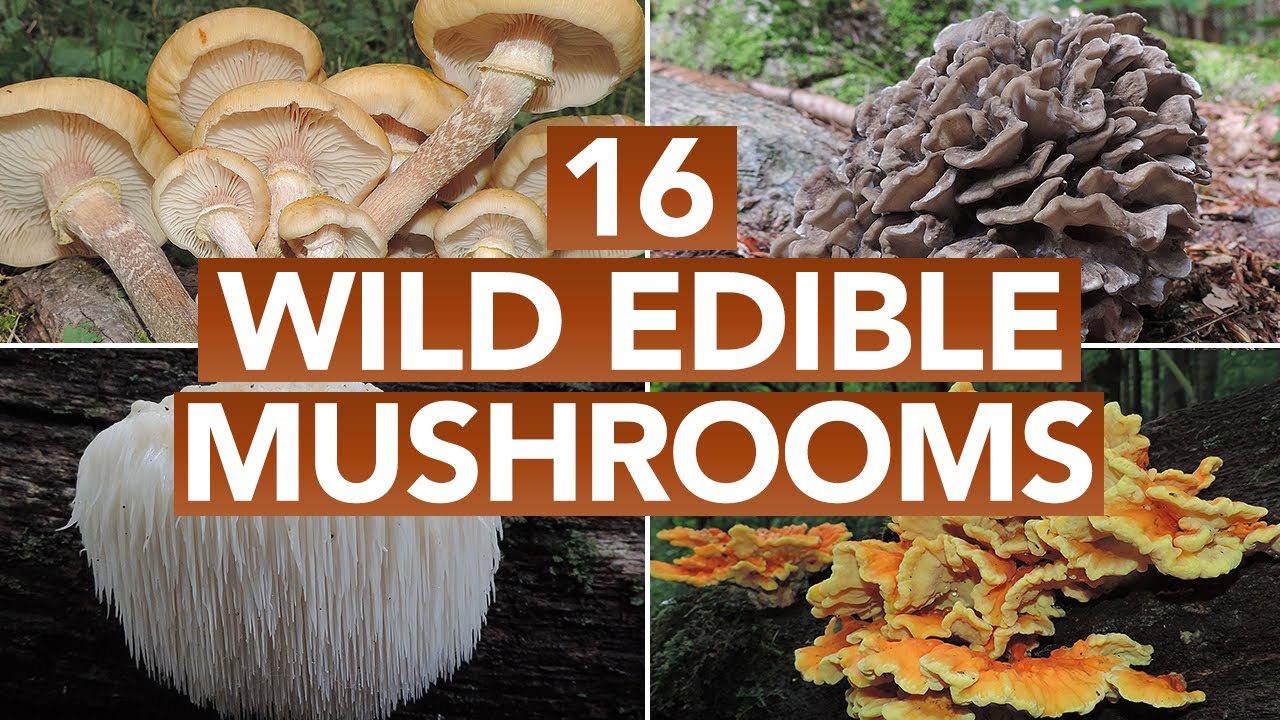

The Heavy Hitters: Popular Edible Types of Wild Mushrooms

If you want to talk about the royalty of the forest floor, you have to start with the Morel (Morchella). These look like little honeycombed brains on a stick. They’re elusive. They love burned-over areas and dead elm trees. Chefs lose their minds over them because of that nutty, earthy flavor that you just can't replicate in a lab. Morels are usually the "gateway drug" for foragers because their distinctive look makes them harder—though not impossible—to confuse with toxic lookalikes.

Then there are Chanterelles. They’re beautiful. Often bright yellow or orange, they smell faintly of apricots. If you find a patch, you've hit the jackpot. But here's the kicker: beginners often confuse them with Jack-o'-Lantern mushrooms. The difference? Chanterelles have "false gills" that are actually ridges on the flesh, whereas Jack-o'-Lanterns have true, blade-like gills. Also, Jack-o'-Lanterns can actually glow in the dark, which is cool, but they will absolutely wreck your digestive system.

Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are another fan favorite. You'll find them growing in shelf-like clusters on dying hardwood trees. They’re ubiquitous. They actually smell a bit like anise or seafood. Because they grow on wood rather than in the dirt, they’re usually cleaner than other wild finds.

The Lions Mane and the "Chicken"

Ever seen something that looks like a white, shaggy pom-pom hanging off a tree? That’s Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus). It’s weird. It doesn’t have gills or pores; it has teeth-like spines. Research, including studies by experts like Paul Stamets, suggests these might actually help with nerve regeneration and cognitive function. They taste like lobster when sautéed in butter. Seriously.

🔗 Read more: Finding Another Word for Calamity: Why Precision Matters When Everything Goes Wrong

Then there’s the Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus). It’s bright, garish orange and yellow. It grows in massive brackets. It literally has the texture and flavor of dark-meat chicken. It’s one of the "Foolproof Four," a group of mushrooms so distinct they are considered safe for beginners. But even then, if it’s growing on a hemlock tree, it can absorb toxins that’ll make you sick. Context matters.

The "Never Touch These" List

We have to talk about the Amanitas. This genus contains some of the most beautiful and most lethal types of wild mushrooms on the planet. The Death Cap (Amanita phalloides) is responsible for the majority of mushroom-related fatalities worldwide. It’s unassuming. It looks like a standard white or greenish mushroom you’d find at a grocery store.

The scary part? It contains amatoxins. These toxins don't kill you immediately. You eat it, you might feel a bit sick, then you feel better for a day or two. Meanwhile, your liver is literally dissolving. By the time you realize something is wrong, it’s often too late for anything but a transplant.

- Destroying Angel: Pure white, elegant, and contains the same deadly toxins as the Death Cap.

- Fly Agaric: The "Mario mushroom." Red with white spots. It’s hallucinogenic but also toxic, causing sweating, pupil dilation, and intense confusion.

- False Morels: These look like morels but have a wrinkled, brain-like cap that is reddish-brown. They contain gyromitrin, which turns into rocket fuel (monomethylhydrazine) in your stomach. Not a joke.

Why "Rules of Thumb" Will Get You Killed

People love shortcuts. "If an animal eats it, it's safe." Wrong. Squirrels can eat many mushrooms that would liquefy a human liver. "If it peels, it's edible." Nope. Death Caps peel perfectly. "Silver spoons turn black in poisonous mushrooms." This is a dangerous myth from the Middle Ages.

There is no single "test" for toxicity. You have to identify the mushroom down to the species level. This involves looking at the cap, the gills, the stem (stipe), the base (vulva), and even doing a spore print. A spore print is basically the mushroom's fingerprint. You cut the cap off, place it on a piece of paper, cover it with a bowl, and wait a few hours. The color of the dust (spores) that falls out is a critical diagnostic tool.

💡 You might also like: False eyelashes before and after: Why your DIY sets never look like the professional photos

Micro-Environments and Symbiosis

Mushrooms are picky. Many types of wild mushrooms are mycorrhizal, meaning they have a symbiotic relationship with specific trees. Boletes, known for having a spongy pore surface instead of gills, often hang out with oaks or pines. If you find a Porcini (Boletus edulis), look up. You'll likely see a conifer or a hardwood that is feeding sugar to the fungus while the fungus provides water and minerals to the tree. It’s a subterranean trade network that’s been running for millions of years.

The Ethics and Logistics of Foraging

Don't be the person who rips everything out of the ground. Foraging is a delicate balance. Many experts suggest using a mesh bag so that as you walk, you’re inadvertently spreading spores back onto the forest floor. It’s like a "pay it forward" system for fungi.

Also, location is everything. Mushrooms are bio-accumulators. They suck up everything from the soil, including heavy metals and pesticides. Never forage near a busy road, a golf course, or an old industrial site. You’re not just eating the mushroom; you’re eating whatever that mushroom has been drinking for the last week.

Getting Started Without Dying

If you're actually serious about exploring types of wild mushrooms, don't start with a book. Books are great, but they're static. Start with a local mycological society. Every major region has one. These are groups of "fungi nerds" who do "forays"—group walks where experts can show you things in real life.

Essential Gear for the Aspiring Mycologist

- A high-quality field guide: Get one specific to your region (e.g., Mushrooms of the Northeast).

- A sharp knife: For clean cuts that don't damage the underground mycelium.

- A brush: To clean off dirt in the field (saves a headache later).

- A magnifying glass: For looking at tiny details like gill attachment.

- A paper bag: Never use plastic; mushrooms turn into slimy mush in plastic bags within an hour.

Actionable Steps for Foraging Safety

Before you even think about putting a wild mushroom in a pan, follow this protocol. It is the gold standard for survival in the world of mycology.

📖 Related: Exactly What Month is Ramadan 2025 and Why the Dates Shift

Identify it three times. Identify it in the field using a book. Identify it at home using a different book. Then, have an expert or a highly experienced forager confirm it. If there is even a 1% doubt, throw it out. "When in doubt, throw it out" is the only mantra that matters.

Keep a "control" sample. If you do decide to eat a wild mushroom, save one raw, whole specimen in the fridge. If you get sick, the doctors need to see exactly what you ate to treat you correctly.

Eat a tiny amount first. Even edible mushrooms like Chicken of the Woods can cause allergic reactions in some people. Sauté a piece the size of a fingernail, wait 24 hours, and see how your body reacts.

Cook everything. Almost no wild mushroom should be eaten raw. Many contain mild toxins or chitin (which is hard to digest) that are broken down by heat. Sautéing isn't just for flavor; it's for safety.

The world of fungi is massive and mostly unexplored. We've only identified about 5% of the estimated global fungal species. While types of wild mushrooms offer incredible culinary and medicinal potential, they demand respect. Treat them like a wild animal: beautiful to look at, but capable of biting if you get too close without knowing what you're doing.

For your next move, get your hands on a regional field guide like those by David Arora or Gary Lincoff. Start by simply identifying what’s in your yard without the intention of eating it. Once you can consistently identify five species with 100% accuracy, you're ready to start your journey as a forager.