You're standing on a wooden pier in the Everglades and see a snout breaking the surface of the dark water. Someone yells, "Look, an alligator!" while the person next to them swears it’s a crocodile. Honestly, unless you've spent years staring at these living fossils, it’s easy to get them mixed up. They both look like prehistoric nightmares with too many teeth. But they aren't the same. Not even close.

Evolutionary biology tells us these two families split apart about 80 million years ago. To put that in perspective, humans and chimpanzees split only about 6 million years ago. Alligators and crocodiles are more different from each other than we are from apes. If you want to understand the different types of crocodiles and alligators, you have to look past the scales and start looking at the architecture of their skulls and the chemistry of their blood.

The Snout and the Smile

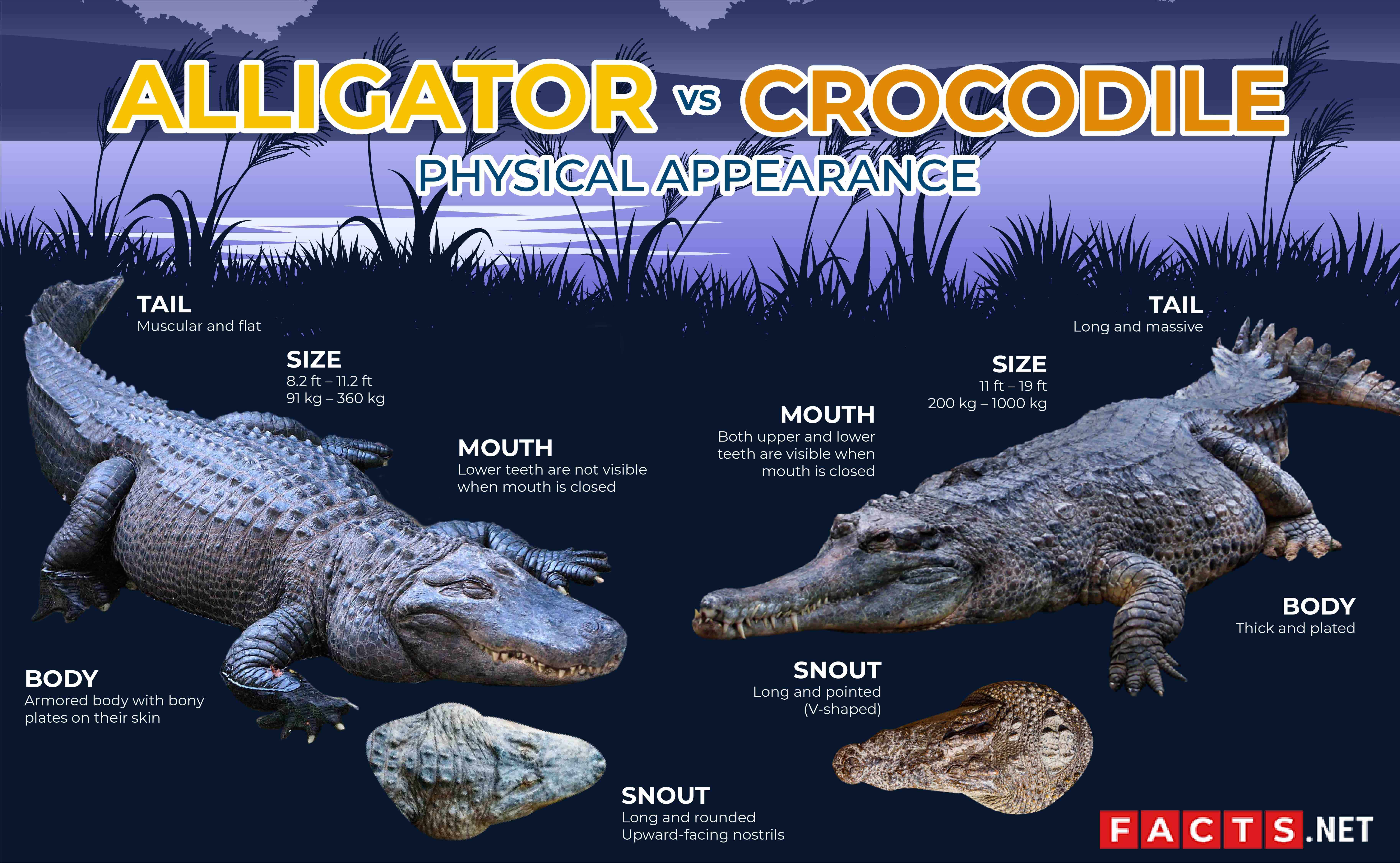

The easiest way to tell them apart is the "teeth check." When an alligator shuts its mouth, you mostly see the upper teeth pointing down. It looks relatively tidy, if a giant lizard mouth can ever be called tidy. But crocodiles? They have a jagged, toothy "grin" where the fourth tooth on the lower jaw sticks out over the upper lip. It’s messy. It’s intimidating.

Then there is the snout shape. Alligators usually have a broad, U-shaped snout. It’s built for power—crushing turtle shells and heavy bones. Crocodiles generally sport a more pointed, V-shaped snout. This makes them a bit more hydrodynamic for catching fast fish, though the massive Saltwater crocodile breaks this rule a bit with its sheer bulk.

The Saltwater Crocodile: The King of the World

The Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) is the undisputed heavyweight champion of the reptile world. These things are massive. We are talking about males that regularly reach 17 feet, with legendary specimens like "Lolong" from the Philippines measuring over 20 feet before he passed away in 2013.

They are also incredibly adaptable. They have specialized salt glands on their tongues that excrete excess salt, allowing them to thrive in the open ocean. This is why you’ll find them in the brackish waters of Northern Australia, all through Southeast Asia, and even occasionally swimming far out at sea. If you see one of these in the wild, you aren't looking at a swamp dweller; you're looking at an apex predator that has remained virtually unchanged since the Cretaceous.

💡 You might also like: North Shore Shrimp Trucks: Why Some Are Worth the Hour Drive and Others Aren't

The American Alligator: The Success Story

If the Saltie is the king of the ocean, the American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) is the king of the golf course. Found across the Southeastern United States, these gators are a massive conservation success story. Back in the 1960s, they were on the verge of extinction. Today? There are millions of them.

They are freshwater specialists. Unlike their croc cousins, they lack those efficient salt-excreting glands. While a gator can tolerate salt water for a few hours or even a couple of days, they eventually have to head back to the marshes and lakes of Florida, Louisiana, and Georgia. They are also surprisingly "chilled out" compared to crocodiles. Don't get me wrong—they will absolutely bite you—but they tend to be less overtly aggressive than the Nile or Saltwater crocs.

Diving Into the Specific Types of Crocodiles and Alligators

Most people think there are just "the big two," but there are actually over two dozen species in the order Crocodilia. They are scattered across every continent except Antarctica and Europe.

The Nile Crocodile: The Man-Eater

When you watch nature documentaries about wildebeests crossing a river and getting snatched, you’re watching the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus). These are arguably the most dangerous to humans. Because they live in close proximity to human settlements along the Nile and throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, encounters are frequent and often fatal. They are opportunistic. If it moves and it’s near the water, it’s food.

The Gharial: The Weird Cousin

You cannot talk about types of crocodiles and alligators without mentioning the Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus). Found in the rivers of India and Nepal, they look like a crocodile that went on a very extreme diet. Their snouts are incredibly long and thin, lined with dozens of needle-like teeth. They aren't built for eating people; they are specialized fish hunters. Sadly, they are also critically endangered. Habitat loss and fishing nets have decimated their numbers, leaving only a few hundred breeding adults in the wild.

📖 Related: Minneapolis Institute of Art: What Most People Get Wrong

Caimans: The South American Connection

Caimans are part of the alligator family, but they have their own distinct vibe. They are mostly found in Central and South America.

- Black Caiman: This is the big boy of the Amazon. It can grow up to 16 feet and is the only caiman that truly rivals the big crocodiles in size and danger.

- Spectacled Caiman: Named for a bony ridge between their eyes that looks like the bridge of glasses. They are incredibly common and have been introduced (illegally) to places like Florida.

- Dwarf Caimans: These are the smallest of the bunch, often staying under 5 feet. They are tough, armored, and live in fast-flowing forest streams.

Survival in the Extreme

One of the coolest things about the types of crocodiles and alligators is how they handle the weather. Alligators are much more cold-tolerant than crocodiles. In North Carolina, the northernmost edge of their range, alligators have been known to survive frozen ponds by sticking their snouts above the ice and letting the water freeze around them. They go into a state called brumation. Their heart rate drops to almost nothing. They just sit there, frozen in place, until the thaw.

Crocodiles can't do that. Most crocodiles are strictly tropical. If the water gets too cold, their systems simply shut down and they die. This is why you don't find crocodiles in the Carolinas or North China.

The Science of the "Alligator Hole"

Alligators are actually ecosystem engineers. In the Florida Everglades, during the dry season, they use their tails and snouts to dig out depressions in the limestone. These "alligator holes" retain water when the rest of the marsh dries up.

It's a survival tactic for the gator, sure, but it also provides a sanctuary for fish, turtles, and wading birds. Without the alligator, the biodiversity of the Everglades would collapse. Crocodiles don't really do this to the same extent, making the alligator a vital part of the American landscape's physical structure.

👉 See also: Michigan and Wacker Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong

How to Stay Safe in "Croc Country"

Whether you are trekking through the Daintree Rainforest in Australia or kayaking in the Louisiana bayous, respect is the name of the game. These animals are ambush predators. They don't hunt by chasing you down on land (though they can move surprisingly fast for short bursts); they hunt by being invisible.

- Stay back from the water’s edge: Most attacks happen within five feet of the shoreline.

- Avoid twilight: They are most active at dawn and dusk. That’s when their night vision gives them the ultimate advantage.

- Never feed them: A fed alligator is a dead alligator. Once they associate humans with food, they become "nuisance" animals and usually have to be euthanized.

- Watch for nests: From June to September, mother gators and crocs are extremely protective of their mounds of rotting vegetation (the nests). Don't go poking around.

Moving Forward: Protecting the Modern Dinosaur

Understanding the different types of crocodiles and alligators isn't just for trivia night; it’s about conservation. We almost lost the American Alligator and the Chinese Alligator. We are currently at risk of losing the Gharial and the Philippine Crocodile.

These animals are the ultimate survivors. They outlasted the T-Rex. They watched the continents drift apart. To lose them now because of river pollution or the leather trade would be a biological tragedy. If you want to help, support organizations like the Crocodile Specialist Group (CSG) or the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). They work on the ground to mitigate human-wildlife conflict, which is the biggest threat these reptiles face today.

The next time you see a dark shape drifting in a pond, look for the "grin." Check the snout. Respect the millions of years of engineering that went into that animal. Whether it's a 20-foot Saltie or a 4-foot Dwarf Caiman, you're looking at a masterpiece of evolution.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Identify your local species: If you live in a coastal or southern region, use a local wildlife app to see which crocodilians are native to your area.

- Visit an AZA-accredited zoo: Seeing a Gharial or a Black Caiman in person is the best way to appreciate the sheer diversity of their forms.

- Practice "Be Crocwise": If traveling to Northern Australia or Southeast Asia, always check for "Croc Warning" signs and follow local advice—crocodiles in these areas are far more aggressive than American alligators.

- Support Sustainable Habitats: Reduce your use of plastics and chemicals that runoff into watersheds, as apex predators like crocodilians bioaccumulate toxins from their environment.