You’ve seen the thumbnails. A guy with lighting so dramatic it looks like he’s in a Batman movie, pointing at a "secret" muscle while promising a six-pack in four minutes. Honestly? It's exhausting. Most of the advice floating around about types of ab workouts is either outdated, physiologically incomplete, or just flat-out dangerous for your lower back.

Abs aren't just one slab of meat.

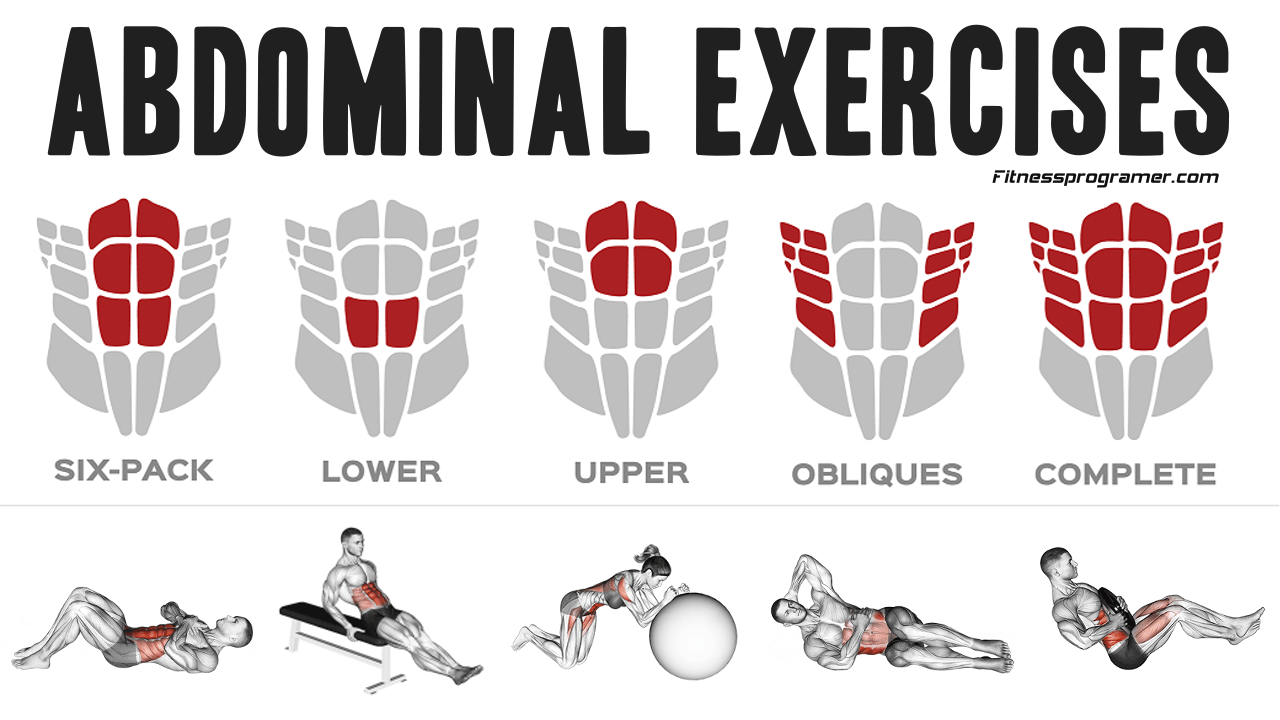

If you want a core that actually functions—meaning you can pick up a heavy grocery bag without throwing out your back—you have to stop thinking about "crunches" as the holy grail. Your core is a complex 360-degree system. It involves the rectus abdominis (the "six-pack"), the internal and external obliques, the transverse abdominis (your deep internal corset), and even the erector spinae in your back. Most people just spam one type of movement and wonder why their posture looks like a question mark.

The Core Stability vs. Core Flexion Debate

For decades, the "crunch" was king. You lie down, you curl up, you repeat until it burns. But back experts like Dr. Stuart McGill, a professor emeritus at the University of Waterloo, have spent years pointing out that excessive spinal flexion—basically, bending your spine over and over—can put a massive amount of pressure on your intervertebral discs. Think of your spine like a credit card. If you bend it back and forth enough times, eventually, it’s going to snap or wear out.

That’s why modern types of ab workouts have shifted heavily toward "anti-movement" training.

Anti-Extension: Keeping the Arch Away

This is basically about resisting the urge to let your back arch like a banana. When you’re doing a deadbug or a front plank, you are training anti-extension. Your abs are working to keep your pelvis tucked and your spine neutral. If you feel your lower back pinching during a workout, you’ve failed the anti-extension test.

It's subtle. You won't feel that "burning" sensation as quickly as you do with crunches, but it's arguably more functional. Dr. McGill’s "Big Three" exercises focus heavily on this kind of stability because it protects the spine while building a rock-solid foundation.

💡 You might also like: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

Anti-Rotation: The Secret to Real Power

Ever heard of a Pallof Press? You stand sideways to a cable machine or a resistance band, hold the handle at your chest, and press it straight out in front of you. The band is trying to pull your torso toward the machine. Your job? Don't let it. This is anti-rotation.

Athletes love this. Baseball players, golfers, and boxers use anti-rotation to build the kind of core strength that allows them to transfer power from the ground up through their hands. If you can't resist rotation, you can't effectively generate it when you actually want to.

Rotational and Lateral Types of Ab Workouts

We move in three dimensions, yet most gym-goers only train in one.

Side planks are the most common example of lateral stability. You’re resisting gravity pulling your hips toward the floor. But you can take it further with things like suitcase carries. Grab one heavy dumbbell, hold it at your side like a suitcase, and walk. Your obliques on the opposite side have to fire like crazy to keep you from tipping over. It’s incredibly simple. It’s also incredibly effective.

Then there is actual rotation. Think woodchoppers or Russian twists—though you have to be careful with twists. If you’re sitting on your butt and cranking your spine around with a heavy medicine ball, you might be doing more harm than good to your discs. True rotational work usually happens from the hips. The core acts as the stiff link that transmits that power.

The "Lower" Abs Myth and How to Actually Target Them

Science time: You cannot "isolate" your lower abs. The rectus abdominis is one long muscle. When it contracts, it contracts. However, you can emphasize the lower region by changing the "anchor" point of the movement.

📖 Related: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

In a crunch, your hips are the anchor and you’re moving your ribcage toward them. This hits the upper fibers more. In a leg raise or a "reverse crunch," your ribcage is the anchor and you’re pulling your pelvis toward your chest. This creates more tension in the lower portion of the muscle.

The problem? Most people don't use their abs for leg raises. They use their hip flexors. If your lower back is arching off the floor while you drop your legs, your abs have effectively quit the job, and your hip flexors have taken over. To fix this, you have to keep your lower back pressed into the floor like you’re trying to squash a grape. If you can’t do that, your legs are going too low.

Isometric vs. Dynamic Training

Should you hold still or should you move?

The answer is both.

- Isometric exercises like planks, hollow body holds, and L-sits build endurance. They teach your muscles how to stay "on" for long periods. This is vital for posture.

- Dynamic exercises like hanging knee raises or cable crunches build the actual thickness of the muscle. If you want your abs to pop through your skin, they need hypertrophy, just like your biceps or chest.

Hypertrophy requires load. Doing 100 bodyweight crunches is mostly a waste of time after the first week. You’d be better off doing 10 to 12 reps of a weighted movement where you’re actually struggling by the end.

Why Your Diet is Still the Boss

We have to talk about it. You can have the strongest core in the world, capable of taking a punch from a heavyweight champion, but if it's covered by a layer of subcutaneous fat, you won't see it. This is where the "abs are made in the kitchen" cliché comes from.

👉 See also: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

It’s true. Mostly.

But "made in the kitchen" only refers to visibility. A core that is "made" solely through dieting is skinny, not strong. You need the structural integrity that comes from diverse types of ab workouts to ensure that once the fat is gone, there’s actually something there to look at. Plus, a strong core makes you better at every other lift. You’ll squat more, deadlift more, and even overhead press more if your midsection isn't acting like a wet noodle.

Mistakes That Are Killing Your Gains

Stop pulling on your neck. Seriously. If you’re doing crunches and your hands are behind your head, don't yank. You’re just straining your cervical spine. Touch your ears or cross your arms over your chest instead.

Stop holding your breath. This is a big one. You need to learn how to breathe "behind the shield." This means keeping your abs tight while still taking shallow, controlled breaths. If you hold your breath during a heavy set of core work, your blood pressure spikes and you fatigue faster.

Stop ignoring your back. A balanced core requires strong lower back muscles. If you only work the front, you’ll develop a "hunched" posture because your front is pulling harder than your back can resist. Include bird-dogs or back extensions to keep things even.

Actionable Steps for a Better Core

Don't just add an "ab day" at the end of the week. Your core can handle frequency, but it needs variety.

- Pick one anti-extension move: Start with the deadbug. Focus on keeping your back flat.

- Pick one anti-rotation move: Use a resistance band for Pallof presses. 3 sets of 10-12 reps per side.

- Pick one "lower" emphasis move: Try reverse crunches, but focus on curling your pelvis, not just swinging your legs.

- Add a weighted movement: Cable crunches are great here. Go heavy enough that 15 reps is your limit.

- Do it 3 times a week: Consistency beats intensity every single time.

Start with the "deadbug" today. Lie on your back, arms up, knees bent at 90 degrees. Slowly lower the opposite arm and leg while forcing your spine into the floor. If you feel a "gap" form between your back and the floor, stop. That's your current limit. Work on closing that gap, and you'll be ahead of 90% of the people at your local gym.