Ever looked at a two stroke engine diagram and wondered how something with so few moving parts actually works? It’s basically magic. Or, more accurately, it’s a masterclass in fluid dynamics and mechanical efficiency that’s been powering everything from your weed whacker to legendary GP motorcycles for decades. Unlike the four-stroke engines in your SUV—which are cluttered with valves, cams, and timing belts—the two-stroke is lean. It’s mean. It gets the job done in half the movements.

You’ve probably heard people say these engines are "dirty" or "loud," and yeah, there’s some truth to that. But honestly, if you want power-to-weight ratios that make your head spin, you can't beat them. We’re talking about a design that fires every single time the piston hits the top of its stroke. Every. Single. Time.

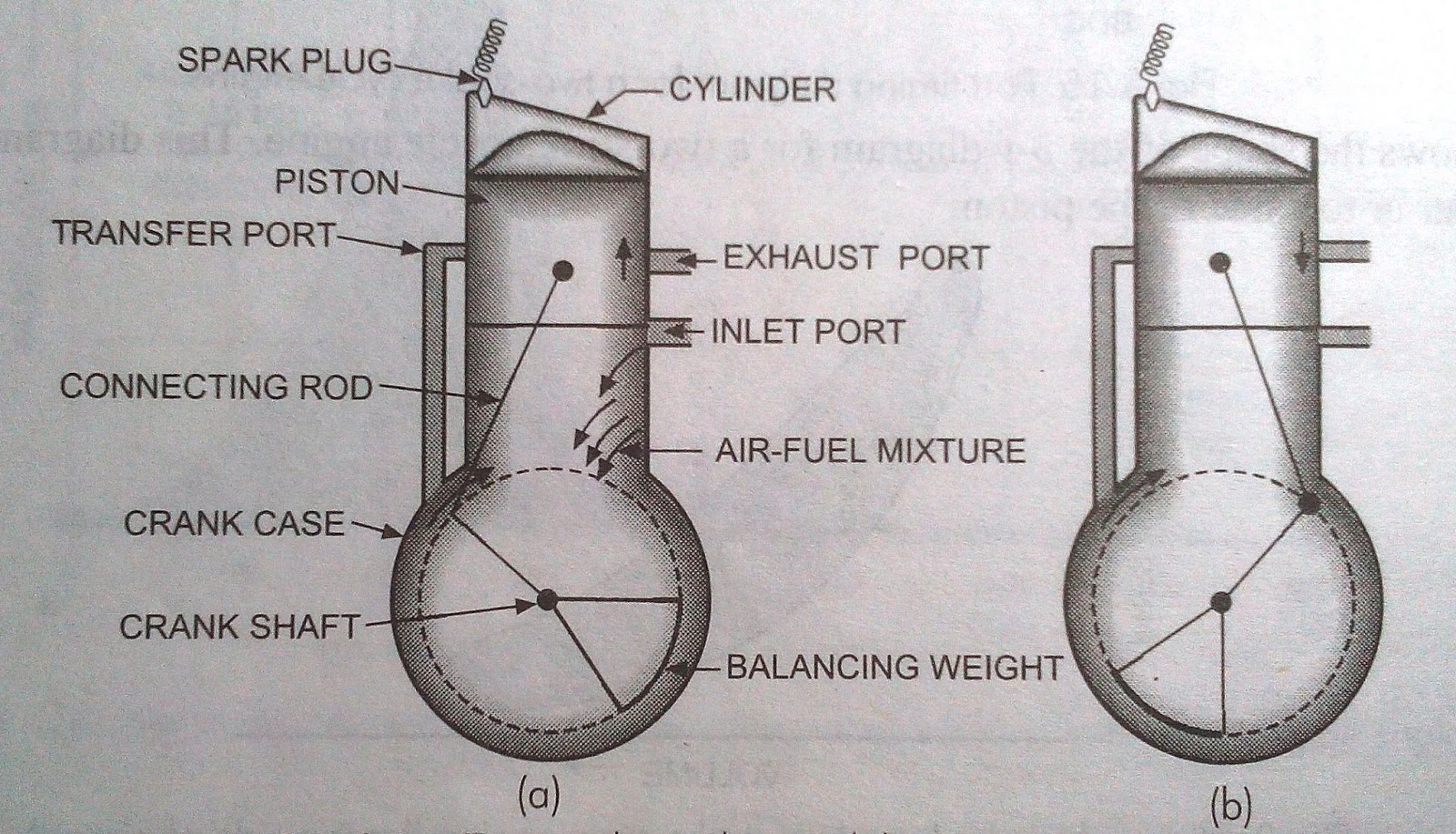

Anatomy of the Two Stroke Engine Diagram

When you pull up a two stroke engine diagram, the first thing that hits you is the lack of a traditional valvetrain. There are no overhead cams. No intake valves that look like tiny mushrooms. Instead, the cylinder wall itself acts as the valve. It's got holes in it—technically called ports.

The Ports are the Secret Sauce

Most diagrams show three main players: the intake port, the exhaust port, and the transfer port. The piston moves up and down, and as it does, it physically uncovers these holes. Imagine a sliding door. When the piston is at the bottom (Bottom Dead Center or BDC), the transfer port is wide open, letting fresh fuel and air mixture scream into the combustion chamber. At the same time, the exhaust port is open, letting the old, burnt gases escape.

Wait. If they’re both open at the same time, doesn’t the fresh stuff just blow out with the exhaust?

Kinda. That’s called "scavenging." Engineers like those at Rotax or Yamaha spend thousands of hours shaping the expansion chamber (that fat part of the exhaust pipe) to create a pressure wave. This wave actually pushes the fresh fuel back into the cylinder right before the piston closes the port. It’s a delicate dance of physics that doesn't show up on a static drawing but makes all the difference in real-world horsepower.

One Revolution, Two Stages

In a four-stroke, you have Intake, Compression, Power, and Exhaust. Four distinct steps. In our two stroke engine diagram, we cram all of that into just two movements: Up and Down.

The Upward Stroke (Compression and Intake)

As the piston moves toward the spark plug, two things happen simultaneously. Above the piston, the air-fuel mixture is being squeezed into a tiny, volatile space. Below the piston, in the crankcase, a vacuum is created. This vacuum sucks fresh air and fuel in through the reed valve. It's an elegant use of space. The "bottom" of the engine is doing work just as hard as the "top."

The Downward Stroke (Power and Exhaust)

The spark plug fires. BOOM. The explosion drives the piston down. This is your power stroke. But as the piston descends, it’s also compressing the mixture that was just sucked into the crankcase. As it nears the bottom, the exhaust port is uncovered first, letting the high-pressure waste gases bolt for the exit. A split second later, the transfer port opens, and that compressed mixture in the crankcase rushes up into the cylinder, pushing out the rest of the exhaust.

It’s fast. In a dirt bike idling at 1,500 RPM, this whole cycle happens 25 times every single second. At full tilt? Maybe 150 times a second. Your eyes can't even track the movement on a screen, let alone in a metal block.

Why the Crankcase is Different

This is where people usually get confused looking at a two stroke engine diagram. In a car, the crankcase is just a bathtub for oil. In a two-stroke, the crankcase is a pressurized induction chamber.

👉 See also: What Really Happened With Project Azorian: The Raising of the K-129

Because the crankcase handles the fuel-air mix, you can’t just fill it with oil. If you did, the engine would just drink the oil and die. This is why you have to "pre-mix" your gas and oil or use an injection system. The oil is suspended in the gasoline, lubricating the crank bearings and cylinder walls as it passes through. It’s a "total loss" system—the oil gets burned and sent out the tailpipe. That’s why two-strokes have that iconic blue smoke and that sweet, nostalgic smell.

The Reed Valve Factor

Many modern diagrams include a reed valve between the carburetor and the crankcase. Think of it as a one-way check valve. It’s usually a thin flap of carbon fiber or fiberglass. When the piston moves up and creates a vacuum, the reeds flap open. When the piston moves down and creates pressure, they snap shut so the fuel doesn't get blown back out through the carb. Without this, the engine would be incredibly "peaky" and hard to start.

Real World Applications: Not Just Chainsaws

While we often associate this design with lawn equipment, the two stroke engine diagram is the blueprint for some of the most powerful machines on Earth.

- Marine Giants: The Wärtsilä RT-flex96C is a two-stroke diesel. It's the size of a multi-story apartment building and powers massive container ships. It produces over 100,000 horsepower.

- Motocross: KTM and Husqvarna have revolutionized the "dirty" image of these engines with Transfer Port Injection (TPI). They use sensors to spray fuel directly into the transfer ports, making them lean enough to pass strict Euro 5 emissions standards while keeping the light weight.

- Snowmobiles: When you’re stuck in ten feet of powder, you need an engine that hits like a sledgehammer instantly. A four-stroke is often too heavy and sluggish for high-alpine carving.

The Expansion Chamber: The "Invisible" Component

If you look at a two stroke engine diagram and don't see a funny-shaped exhaust pipe, you're missing half the story. The expansion chamber is essentially a "supercharger" made of empty space.

It uses sonic waves. When the exhaust port opens, a pressure wave travels down the pipe. It hits the "stinger" or the cone at the end and reflects back. If the pipe is tuned correctly, that reflected wave hits the exhaust port exactly when the fresh fuel is trying to escape, "plugging" the hole with pressure and forcing the fuel back in. It’s a phenomenon called supercharging by resonance. This is why a tuned pipe can suddenly double the horsepower of a small engine once it hits a certain RPM—the "power band."

Common Misconceptions and Limitations

It’s not all wheelies and smoke rings. Two-strokes have a reputation for being unreliable, but that’s usually because they’re run at the limit. Because they fire twice as often as a four-stroke, they generate a lot of heat. Heat kills engines.

- "They don't last as long": True, generally. The rings have to slide over ports, which causes more wear than a smooth cylinder wall. Plus, the lubrication isn't as consistent as a pressurized oil pump system.

- "They have no torque": Partially false. While they lack the low-end "thump" of a big four-stroke, their torque-per-liter is actually quite high; it just happens higher up in the rev range.

- "They're illegal": Not even close. While they’ve vanished from the street-legal motorcycle market in many countries, they are thriving in off-road, marine, and industrial sectors thanks to electronic fuel injection.

Troubleshooting Your Engine Using the Diagram

If your engine isn't starting, use the two stroke engine diagram as a mental map. You only need three things: Compression, Spark, and Fuel.

- Check the Crank Seals: If the seals on the ends of your crankshaft are leaking, you lose that vital crankcase pressure. The engine might have "compression" at the spark plug hole, but it can't suck fuel in. This is a common "phantom" problem that drives people crazy.

- Look at the Reeds: If the engine pops or backfires through the carb, your reed valves are likely chipped or worn. They aren't sealing, letting the "down" stroke push fuel the wrong way.

- Exhaust Blockage: Because these engines burn oil, the exhaust port can get clogged with carbon (soot). If the "waste" can't get out, the "fresh" can't get in. It's like trying to breathe in while holding your breath.

Actionable Steps for Maintenance

Don't just stare at the diagram; get your hands dirty. If you own a two-stroke machine, here is how you keep it from seizing.

Mix your fuel precisely. Using a "glug-glug" method of pouring oil into a gas can is a death sentence. Buy a Ratio-Rite or a similar measuring cup. If the manufacturer calls for 40:1, stick to it. Too much oil makes the engine run "lean" (because there's less gas in the volume of liquid), which actually makes it run hotter.

Clean your air filter after every dusty ride. Since the intake air goes directly into the crankcase and past the bearings, any dirt that gets through acts like sandpaper on your engine's vitals. In a four-stroke, dirt might just foul a valve; in a two-stroke, it can destroy the entire bottom end in minutes.

Monitor your spark plug color. Pull the plug. Is it "cardboard brown"? Perfect. Is it white and blistered? You're running too hot (lean)—stop immediately before you melt a hole in the piston. Is it black and oily? You're "rich"—you're wasting fuel and gunking up your ports.

The beauty of the two-stroke is its simplicity. By understanding how the piston, ports, and crankcase work together, you're not just a user—you're a mechanic. These engines are a dying breed in some areas, but for those who value raw power and mechanical elegance, the two-stroke will always be king.