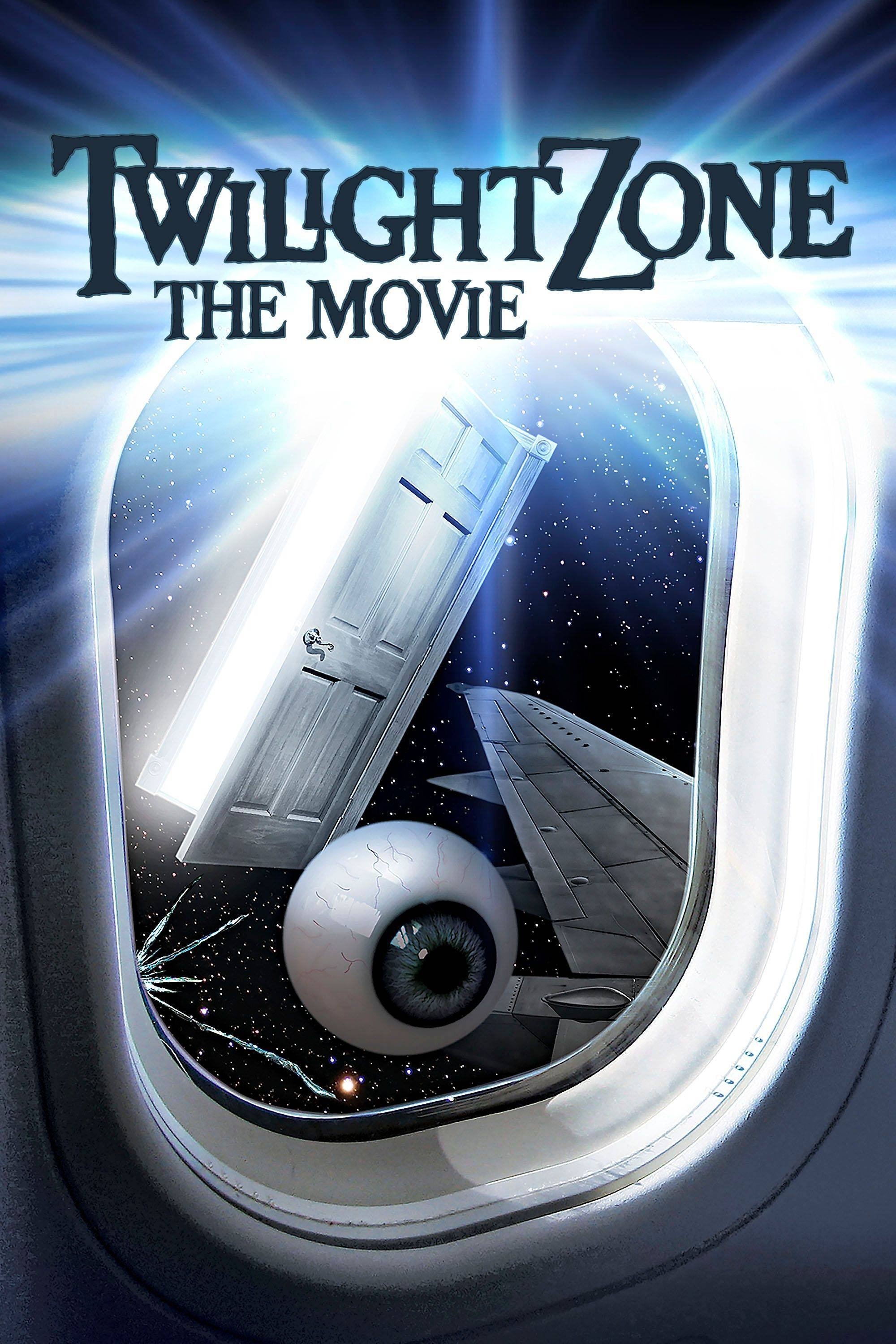

It’s a weird thing, nostalgia. Most people think of Rod Serling’s cigarette smoke and black-and-white irony when they hear the name. But if you grew up in the eighties, or if you’re a total cinephile, you know there’s another version that looms large. I’m talking about Twilight Zone: The Movie. Released in 1983, it was supposed to be this massive, celebratory love letter from the New Hollywood titans to the show that raised them. Steven Spielberg produced it. John Landis, George Miller, and Joe Dante directed segments. It should have been a slam dunk, a popcorn-munching tribute to the fifth dimension. Instead, it became one of the most controversial, haunted, and legally transformative films in the history of the medium.

Honestly, it’s hard to talk about the movie without talking about the tragedy. That’s the elephant in the room. But there’s also the art itself—some of which is genuinely terrifying, and some of which feels, well, a bit dated.

Why Twilight Zone: The Movie Still Haunts Hollywood

If you ask a casual fan about the film, they’ll probably mention the segment with the gremlin on the wing of the plane. John Lithgow was incredible in that. But for those in the industry, Twilight Zone: The Movie isn't just a film; it’s a case study in safety and ethics. During the filming of the segment directed by John Landis, titled "Time Out," a horrific accident occurred. On July 23, 1982, actor Vic Morrow and two child actors, Myca Dinh Le and Renee Shin-Yi Chen, were killed when a helicopter crashed on set.

It changed everything. Literally.

Before this, safety standards on film sets were often treated with a "get the shot at all costs" mentality. The fallout from the crash led to years of litigation and the eventual establishment of much stricter safety protocols by the Screen Actors Guild and the Directors Guild of America. It cast a massive, dark shadow over the entire production. Warner Bros. almost scrapped the whole thing. They didn't, obviously, but the version we got was forever altered by that night. Landis’s segment was heavily edited, and the tonal shift between his gritty, social commentary and Spielberg’s whimsical "Kick the Can" is jarring. It makes for a very strange viewing experience. You’re watching something meant to be entertaining, but you can’t shake the knowledge of what happened behind the scenes.

Breaking Down the Segments: The Good, the Bad, and the Weird

The movie is an anthology, just like the show. It starts with a fun, fourth-wall-breaking prologue featuring Dan Aykroyd and Albert Brooks. They’re driving down a dark road, singing along to Creedence Clearwater Revival, talking about TV themes. It feels very "Landis." Then, things take a turn.

"Time Out" (Directed by John Landis): This stars Vic Morrow as a bigot who gets transported back in time to experience the perspective of those he hates—Jews in Nazi-occupied France, African Americans being chased by the KKK, and Vietnamese villagers. It was meant to be a redemption story. Because of the accident, the ending was lost. What remains is a somewhat truncated, incredibly heavy piece of film. It’s effective, but it feels unfinished because, tragically, it was.

"Kick the Can" (Directed by Steven Spielberg): This is where the movie loses some people. It’s based on the classic episode about elderly people at a nursing home finding the fountain of youth through a game of kick the can. It’s pure, sugary Spielberg. It’s sentimental. It’s brightly lit. Compared to the grit of the other segments, it feels almost out of place. Some people love the whimsy; others find it a bit too cloying for a franchise known for its bite.

"It's a Good Life" (Directed by Joe Dante): This is where the movie gets truly "Twilight Zone." Based on the story by Jerome Bixby, it’s about a little boy named Anthony who has god-like powers and keeps his family hostage in a cartoonish nightmare house. Joe Dante used incredible practical effects here. It’s colorful, surreal, and genuinely creepy. It captures that "uncanny valley" feeling that Serling excelled at, but with an eighties-excess twist.

"Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" (Directed by George Miller): This is the closer. It’s a remake of the famous William Shatner episode. John Lithgow plays the panicked passenger who sees a monster on the wing of the plane. George Miller (the Mad Max mastermind) directs this with an intensity that is almost suffocating. The camera moves constantly. The lighting is harsh. It’s a masterclass in building tension. Even if you know the ending, you’re sweating.

The Legacy of the Gremlin and the Gore

One thing that differentiates Twilight Zone: The Movie from the original 1950s series is the gore. Serling relied on the "theater of the mind." He knew that what you don't see is often scarier than what you do. By 1983, special effects were the name of the game. Rob Bottin, who did the effects for The Thing, worked on this movie.

The gremlin in Miller's segment isn't a guy in a fuzzy suit. It’s a visceral, slimy, terrifying creature. It looks like it belongs in a nightmare. In Joe Dante’s segment, a giant cartoonish rabbit pops out of a television in a sequence that still looks impressive today. This shift toward "creature features" was very much a product of its time. It’s one reason why the movie feels so distinct from the 1985 revival or the Jordan Peele version. It sits in that sweet spot where practical effects were hitting their peak before CGI took over.

Why Does It Still Matter?

You might wonder why we’re still talking about a forty-year-old anthology movie. It’s because it represents a specific moment in Hollywood history. It was the moment the "Movie Brat" generation—the guys who grew up on television—tried to elevate their childhood influences into high art.

It also serves as a reminder of the power of the short-form story. In an era of three-hour blockbusters and serialized streaming shows, there’s something refreshing about a twenty-minute blast of weirdness. The movie proved that the Twilight Zone brand was elastic. It could be horror, it could be fantasy, and it could be a cautionary tale.

Moreover, the film is a testament to the talent of its directors. George Miller’s segment, in particular, is often cited by film students as a perfect example of kinetic storytelling. It’s lean. It’s mean. It doesn't waste a second. If you haven't seen it, honestly, just watch that segment. It’s worth the price of admission alone.

The Elephant in the Room: The Landis Controversy

It would be dishonest to ignore the cloud that hangs over Landis’s career because of this film. The trial lasted years. While Landis and several others were eventually acquitted of involuntary manslaughter, the reputation of the film was forever tied to the tragedy. It’s a somber lesson in the ethics of production. When we watch Twilight Zone: The Movie now, we have to grapple with the reality that lives were lost for the sake of entertainment. It makes the viewing experience complex. It's not just a movie; it's a piece of legal and social history.

That complexity is, in a weird way, very "Twilight Zone." Rod Serling was obsessed with morality, the weight of our choices, and the consequences of our actions. The fact that the film version of his creation became a real-life moral crisis is a bitter irony he probably would have written an episode about.

What to Do Next

If you're interested in exploring the world of the fifth dimension further, don't just stop at the 1983 film. There are layers to this franchise.

- Watch the Original "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet": Find the Season 5, Episode 3 version of the original series starring William Shatner. Compare it to John Lithgow’s performance. It’s a fascinating study in how two different actors handle the same descent into madness.

- Check Out Joe Dante’s Other Work: If you liked the surreal, cartoonish horror of his segment, watch Gremlins or The 'Burbs. He has a very specific "suburban nightmare" vibe that is peak eighties.

- Read "The Twilight Zone Companion": This book by Marc Scott Zicree is the bible for fans. It covers the history of every episode and includes details on the making of the movie and the tragic accident. It’s an essential piece of research if you want to understand the E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness) of the franchise.

- Revisit George Miller’s "Mad Max: Fury Road": To see how the frantic energy from his Twilight Zone segment evolved, watch his later work. You can see the DNA of that gremlin-on-the-wing tension in every high-speed chase.

- Look Up the Set Safety Standards: If you’re a filmmaker or just curious, research the "Section 15" safety bulletins that were created in the wake of the accident. It’s a sobering but necessary look at how the industry protects its workers today.

The movie isn't perfect. It's uneven, sometimes too sentimental, and shadowed by a real-world nightmare. But as a piece of cinema history, it’s indispensable. It’s a reminder that even in the world of the fantastic, the most impactful stories are the ones that have real, human consequences.